Combined set of per-group wikis

This wiki page is very large and may operate slowly. If possible, please split the content into logical chunks and place it on separate linked pages.

This wiki page is very large and may operate slowly. If possible, please split the content into logical chunks and place it on separate linked pages.

Start page

Positive Psychology: Non-Clinical Benefits

From its inception, the main aim of positive psychology has been to make normal lives more fulfilling, to increase happiness in the broadest sense and to allow healthy people to thrive, rather than merely exist. As such, the non-clinical aspects of positive psychology cover a wide range of topics, so for the sake of this wiki, we have taken a broad view of happiness as well as more specific examples of how positive psychology can be utilized to improve different areas of our lives.

For the non-clinical population, positive psychology has given us the tools to be happy; it is up to us whether or not we embrace them.

Contents:

Positive Psychology in Sport

Positive Psychology in the Classroom

Positive Psychology in the Workplace

Practical Applications: Diet & Yoga

If You Only Have 5 Minutes...

Critique

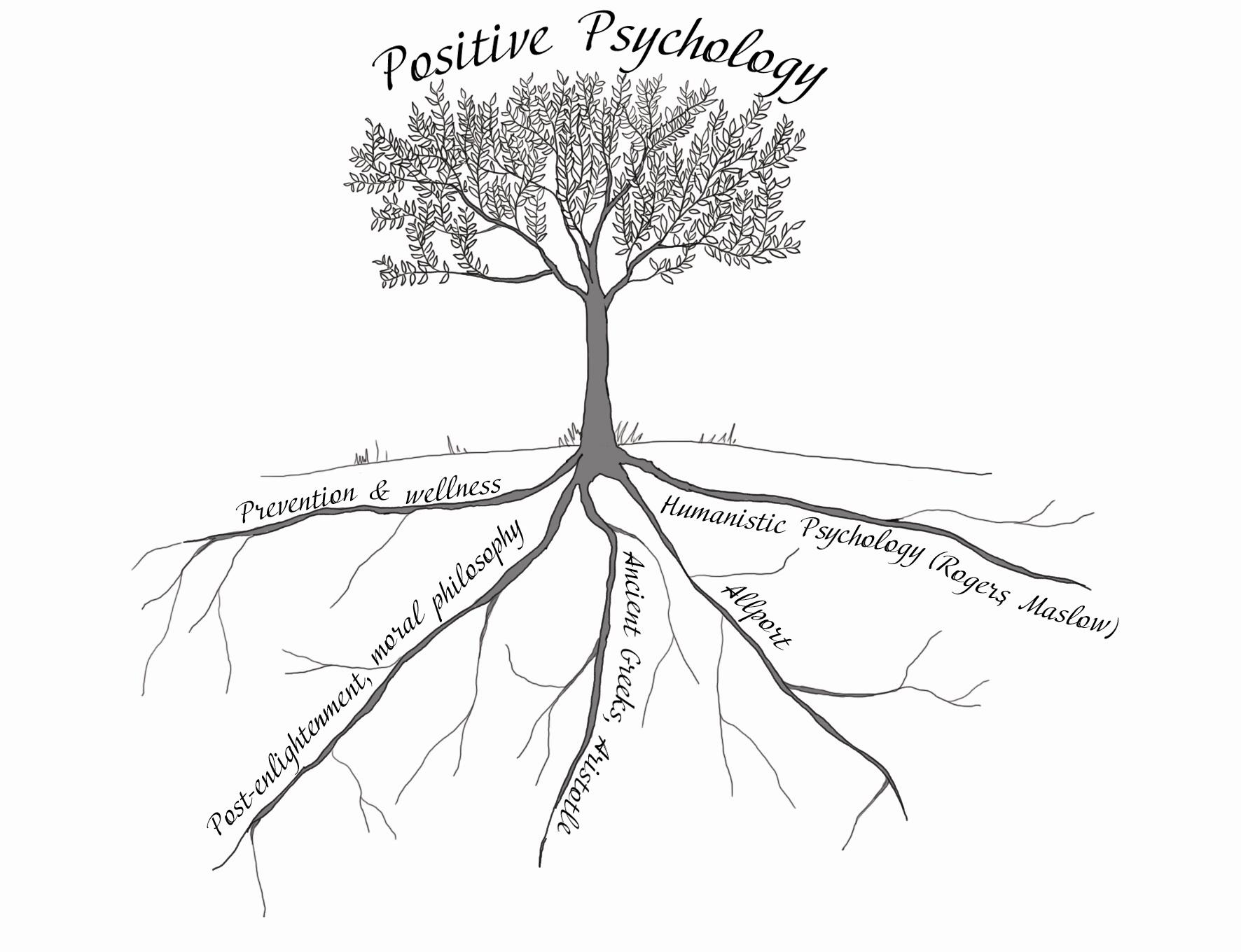

Although positive psychology is a relatively new discipline, the idea that people's everyday lives can be improved by seeking happiness has a rich history.

The Ancient Greeks (adapted from Compton, 2005)

The work of the Ancient Greeks shows that happiness, and our search for it as humans has been a topic worth thinking about for thousands of years. Socrates(469-399 BC) believed that true happiness could be achieved only through knowing the self, while Plato (427-347 BC) used his famous cave metaphor, whereby if a person that has been chained in a cave, such that they can only see the back wall of the cave, they will only be able to see shadows from the real world, and they will come to believe that the shadows are reality. Plato believed that a philosopher was someone who could loosen the chains and turn around to bear the brightness of “the sun” (true knowledge), finally seeing the real truth outside the cave. So people must look beyond the sensory experiences toward a deeper meaning of life and the self, only then can they be happy.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) believed the universal truth was to be found in an intellectual discovery of order in the world. He thought happiness could be found by avoiding emotional extremes and that The Good Life, happiness or eudaimonia(happiness as a function of fulfilling ones potential) would be found in the total context of ones life. He believed there were 12 basic virtues that could be cultivated to lead to happiness. These were courage, liberality, pride (as self-respect), friendliness, wittiness, justice, temperance, magnificence, good temper, truthfulness, shame (or appropriate guilt for our transgressions), and honour.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism, founded by Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) supported the idea that the right policies were the ones that would cause “the greatest good for the greatest number of people” also known as the “greatest happiness principle”. Utilitarianism was the first sector that attempted to measure happiness, creating a tool composed of seven categories, assessing the quantity of experienced happiness (Hefferon and Boniwell, 2011). Pawelski and Gupta (2009) proposed that utilitarianism influences some areas of positive psychology today, such as subjective well being and the pleasurable life.

Religion

Religion not only plays a part in many people's search for everyday happiness, it has played it's part throughout history at telling people how to be happy. All of the major religions impart rules telling their subjects how to be happy, the most obvious being Judaism's Divine Command Theory, the idea that happiness and rewards will follow from following the commands of the divine (The Ten Commandments) (Compton, 2005). Other than explicit rules on how to be happy, religions also have a range of rituals and exercises that can help improve happiness. On the Jewish festival of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), people are encouraged to apologise to people they may have wronged over the year, and to forgive those that have wronged them, so that they can let go of any negative feelings they have over the situation (De Botton, 2012) (For an interesting account of ways in which secular society may benefit from religious practices and traditions see Alain de Botton's Religion for Atheists, 2012).

Religious people have been found to be happier than non-religious people (or at least less depressed) (Smith et al, 2003) and Buddhists have been found to be happier still. This is perhaps because Buddhists seek Sukha, which can be defined as a state of flourishing that arises from mental balance and insight into the nature of reality (similar to the Ancient Greeks) (Ekman et al, 2005). A range of Buddhist techniques (such as yoga and meditation, in particular mindfulness) are now commonly practiced in the West, as they have been found to promote happiness.

How Positive Psychology Found Its Way:

The first use of the term “Positive Psychology” is found 64 years later by the humanist psychologist Abraham Maslow in 1954. Humanistic psychology was a movement in the 50s and 60s that aimed to focus on the study on the whole person, rather than just the parts that were “wrong” with it. Clearly then, it is the most obvious predecessor to positive psychology, and many of the ideas on how to boost people's happiness, rather than just return them to a neutral state of well-being are shared between the disciplines. Humanistic psychology has been widely criticised however, due the lack of a respectable empirical base of evidence that the techniques actually work, which is where positive psychology comes in (Hefferon and Boniwell, 2011)

When Martin Seligman (1942-present) became the president of the American Psychological Association in 1998, 44 years after the first use of the term Positive Psychology, he used it as a chance to focus attention on the new research area he wanted to establish. He wanted to use the ideas suggested by humanist psychology, but build them into a new school focussing on making people's lives better outside of a clinical setting, with a real emphasis on research and evidence, and Positive Psychology as a discipline was born (Seligman, 2003). A journal dedicated entirely to positive psychology was established in 2006, The Journal of Positive Psychology and the field continues to attract more and more attention as it grows.

But how can Positive Psychology actually help individuals to improve their everyday lives and become more happy? Extensive research into the fields of sport, education and the workplace have shown how Positive Psychology can help these areas of life, as well as providing practical exercises, both long and short term to improve overall happiness.

Sport is an area where positive psychology can be very influential. From Motivation and self-confidence to imagery and self–talk. There are many methods used to improve an athletes performance that come from the world of positive psychology. The main goal of positive thinking in sport is to engage in enough positive-thinking practice that a new mental habit of positive thinking becomes embedded in an athletes mind and replaces negative thinking habits that can be as influential as a bad habit in the technical part of the sport.

Self Confidence & Self Talk

Bandura (1997) Theory of Self-Efficacy – defines self efficacy as “beliefs in ones capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments”

Self efficacy is a critical component of what Bandura calls social cognitive theory. Other components of this are agency and personal control. According to Bandura in order for self-efficacy to work the athlete has to believe that they are in full control and that everything that they do they are doing deliberately and intentionally. The athlete needs to believe they have the power to produce specific results, this should motivate them to make these things happen. This will lead the athlete to enter into the competition. Thus, an efficacious athlete is a motivated athlete this means they will work hard and strive to progress to their full potential.

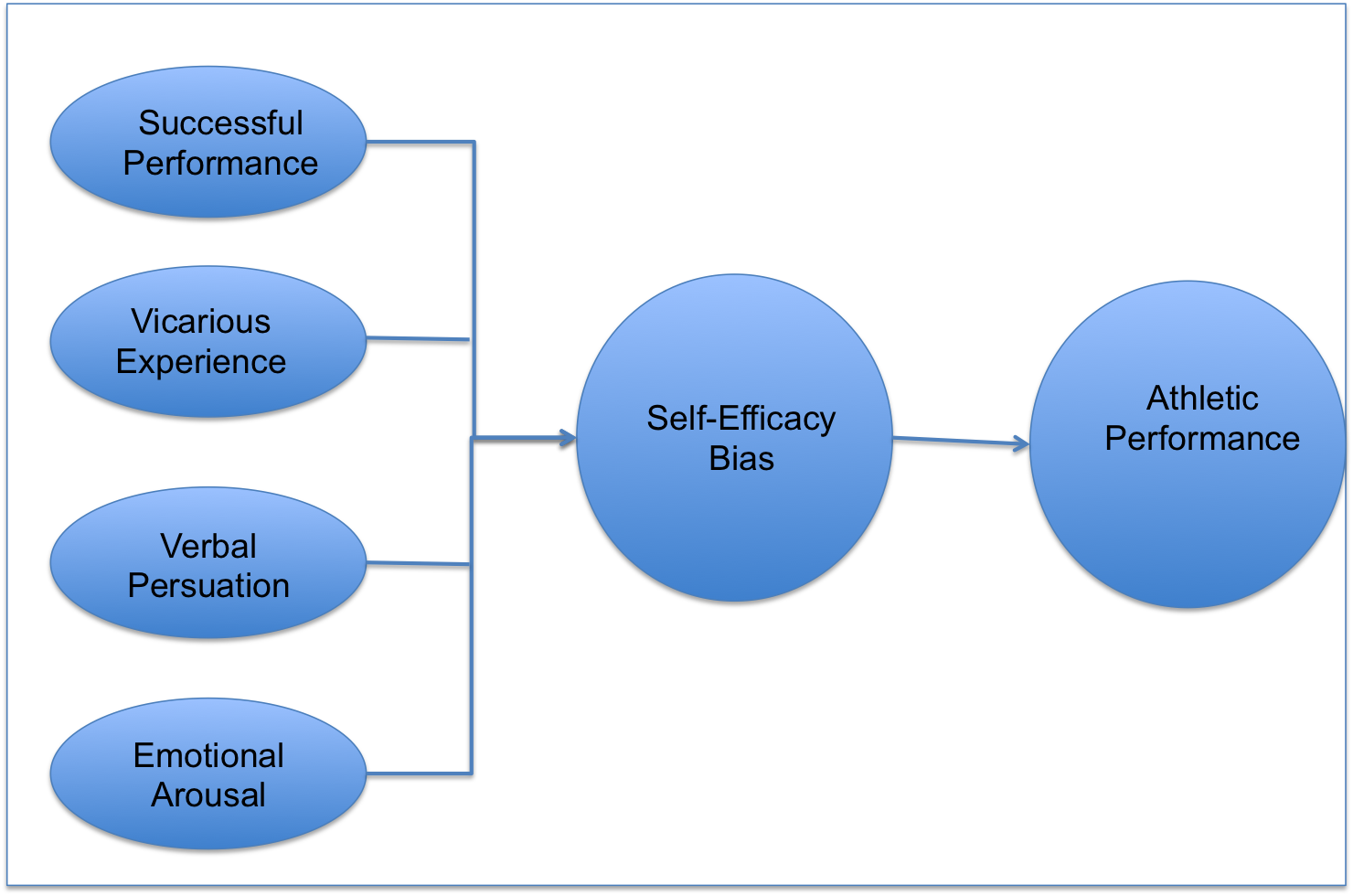

Bandura suggests four fundamental elements effective in developing self-efficacy, these are 1/ Successful Performance, 2/ Vicarious Experience, 3/ Verbal Persuasion and 4/Emotional Arousal

1/ Successful performance

Success, according to Bandura, is key to achieving self-efficacy. With hard tasks this is not always possible at first, so the coach or trainer of the athlete has to lower the difficulty so that the athlete feels success early on. The difficulty should be increased as the simpler tasks are mastered.

2/ Vicarious Experience

An important part of Bandura’s theory is the concept of participatory modelling. Here, the learner first observes a model, either a coach or highly skilled teammate, perform a task successfully. Then the athlete is helped to copy the task successfully, this should give the foundations of being able to do the task in a real situation.

3/Verbal Persuasion

This tends to come from verbal persuasion from the coach, parents or peers. Helpful statements that suggest that the athlete is competent and can succeed more are the best. The best coaching tips are given in a way that do not convey negativism.

“Good tackle, Calum; now remember to concentrate on your leg drive”

Verbal persuasion can also take the form of self talk, this will be discussed further later in the section.

4/ Emotional Arousal

Emotional and physical arousal are factors that can influence readiness for learning. It is the case that we must be emotionally ready and optimally aroused for us to be attentive. Proper attention is important to be able to properly master a skill.

Interestingly in a paper by Beattie et al (2011) who were trying to look for the opposite effect, i.e. that self efficacy is detrimental to performance. They in fact found that in both their experiments performance had a significant, strong and positive relationship with subsequent self-efficacy and predicted 49% of efficacy variance.

Developing self-confidence through self-talk

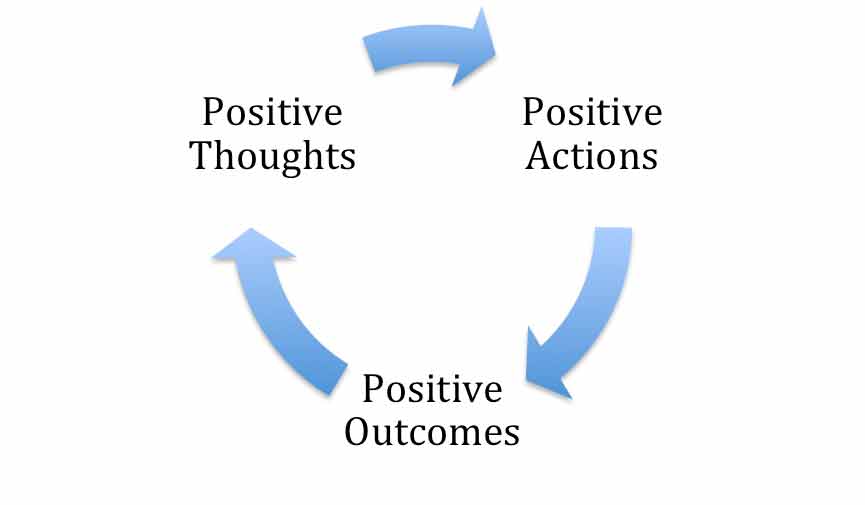

It has been shown that self-efficacy is important to a players performance. Zinsser et al (2001) explain that thoughts effect feelings which in turn affect performance.

Thoughts, Feelings & Performance

Two athletes can be just as talented, have the same experiences in life and in training, but when it comes down to changing performance in training into performance in a match, they can be very different.

For example, in basketball, when there is a free throw, one athlete would think ‘give me the ball, I have made this shot hundreds of times, I’ll make it again’ whereas the other athlete would be thinking ‘What will happen if I miss this?’. In this situation self-talk is important it can do two things, affirm self-efficacy and it can counter negative thoughts. Ultimately self-talk is an effective cognitive technique for reinforcing situation specific self-confidence, and behaviour.

Recently there has been interesting research into the mechanisms through which self-talk facilitates performance. Chroni et al (2008) identified five relevant dimensions. They suggested that self talk can help by enhancing attentional focus, increasing confidence, regulating effort, controlling cognitive and emotional reactions, and triggering automatic execution.

There are however 4 things according to Galanis et al (2011) that moderate the effectiveness of self-talk.

Task characteristics – Hatzigeorgiadis (2006) found that self talk is more effective for increasing attention and concentration, therefore it is thought that self talk is more effective for sports that involve precision (darts, snooker etc.) rather than more physically demanding endurance events. It is also thought that more novel tasks rather than the mastered tasks by an athlete can have larger improvement from self talk.

Type of self-talk – Galanis et al (2011) found that there were two different types of self talk, motivational self talk and instructional self talk. They found that instructional self talk was more effective for fine motor tasks than gross motor tasks, moreover they found that instructional self-talk was more effective that motivational self talk in all motor tasks.

Other interventions to help self confidence in sport

Personal motivational videos – Tracey (2011)

Video has been incorporated into coaching and sport performance for skill development and as a feedback instrument. A case study was carried out to examine the perceived usefulness and benefits such as enhanced motivation, concentration, and anxiety management of using a personal motivation video (PMV). A PMV is a video with music personally created for the athlete designed to produce a positive feeling and increase confidence in the participant. The participant was a 23-year-old male professional mountain bike racer. Results indicated the PMV to be particularly useful for motivation, mental imagery, confidence and emotional management, and concentration, which in turn improved the athletes performance in subsequent runs.

Using negative thinking Positively

Although the thought is a nice one, it is not always possible to be positive all of the time. Sometimes things just don’t go your way. However some negative thinking is normal and can be healthy if you deal with it in the correct way. It can on its own make you perform better, it can act as a deterrent to performing badly as no-one enjoys a bad performance. As Taylor (2009) says there are two types of negative thinking, 1/ give up negative thinking - involves feelings of loss and despair and helplessness and 2/ fire-up negative thinking - involves feelings of anger and energy, of being psyched up, for example. Give up negative thinking drains the athlete, stops them from working to their potential and is not a productive trail of thought.

Fire-up negative thinking on the other hand can work positively towards an athlete’s goal. You focus more to do better in the future because you cannot bare the feeling of ‘failure’ in the past. Your physical intensity goes up and you're bursting with energy. Your focus is on being aggressive and defeating your opponent. However although this can be a technique for increasing performance, it is important that it s not done too much, it can drain energy and if you dwell on the feeling of failure too much it can counteract other more useful positive tools.

The maths test – a regular classroom occurrence most likely dreaded by numerous school pupils. Describing this common classroom scenario, Martin Seligman highlights the value of positive emotions for pupil performance. Seligman illustrates the superior performance of pupils who were asked to remember a ‘happy time’ and of those who were given a surprise piece of chocolate before carrying out the feared maths test – compared to those who sat the test immediately with no such preparation (Eades, Raising Attainment Update, 2008).

This positive emotion approach that Seligman describes along with publications such as Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence (1996) and increasing knowledge of the effectiveness of the early years for later well-being (DfES, 2004) sparked interest in the potential relationship between emotional well-being and educational outcomes (Weare, 2004). These increasing societal interests coupled with growing awareness throughout education circles of the potential importance of well-being, partly fuelled a well-being movement throughout Australian, US and later UK governmental policies e.g. The Every Child Matters Agenda (2003) [see below] These policies have been consequently played out in changes to existing school curricula (Durlak et al., 2011).

Changes to the school curriculum mean that today, promoting the emotional wellbeing of pupils is a primary objective of UK governmental policy and focus is increasingly on the relationships between this and academia – as well as the fostering of further wellbeing related skills and concepts that are thought to be required for the flourishing of people in later life – e.g. resilience; social skills and happiness (Coleman, 2009).

Theoretical Approach

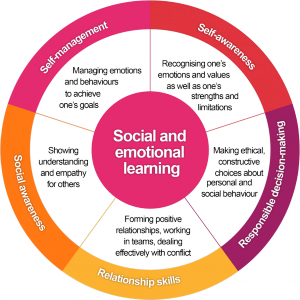

The Social and Emotional Aspects to Learning (SEAL) curriculum is the dominant wellbeing approach in operation throughout UK schools (Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning; DfES, 2005). SEAL is anchored in the emotional intelligence theory of Salovey & Mayer (2004) that was promoted by Goleman (1996) and other psychological theories that highlight the importance of social problem solving (Spivack & Shure, 1974); managing anger (Novaco, 1975) and developing empathy (Feshbach, 1975). The premise of the programme is to foster core social and emotional skills that will consequently optimize positive development in areas of learning; relationships and general health and wellbeing [see diagram below for fuller description] (SEAL; DfES, 2005). Today SEAL is implemented throughout 90% of primary schools and 70% of secondary schools and is generally positively received from pupils Katherine Weare explains (2010).

SEAL is versatile in that it offers a ‘three wave approach’ to implementation enabling adaptation for 1. The Whole School; 2. A specific group showing early 'at-risk' symptoms; 3. A highly targeted approach for a severely at risk group (SEAL; DfES, 2005). Of particular relation to positive psychology in a non-clinical context is ‘wave one’ which encapsulates a whole school approach where implementation of the well-being related curriculum is carried out in a universal manner to all pupils within a school (DCSF, 2008).

Significant instigation of the well-being movement in the first instance came from worrying findings demonstrating that throughout the United Kingdom 10% of 5-16 year olds live with a mental health problem but only 22% of these young people will seek the appropriate help required to overcome their disorder (The UK Office for National Statistics, 2005). As Mustrard (2008) states, the early years of life are increasingly recognised as pivotal for the basis of later mental health capacities such as well-being and resilience. Hence, for these reasons the implementation of programmes in a ‘wave one’ manner that will foster these capacities while acting as prevention mechanisms are becoming increasingly popular throughout school curricula. Read more about the Social and Emotional Aspects to Learning Curriculum here.

In Practice: The FRIENDS Emotional Health Prevention Programme

The FRIENDS for Life programme is a widespread structured prevention programme that is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy informed and is utilised in schools globally – most namely in the UK, US and Australia. The programme has undergone some 12 years of evaluation and piloting, hence its effectiveness is acknowledged by the World Health Organisation. (2004).

Aims of FRIENDS

The dominant aim of FRIENDS is to reduce/prevent negative anxiety-related feelings such as fear and worry in school children while enhancing their self-esteem and resilience.

The Application

The programme is delivered, generally by a trained school nurse, over 10 one-hour sessions. These sessions focus on teaching practical and emotional skills that will facilitate the identification of negative thoughts and feelings and the replacement of these with more positive and adaptive ones. As well as the controlling of emotions; FRIENDS attempts to foster skills that will enable young people to tackle and overcome potential challenges that they may encounter throughout their lives. Implementation of the programme includes work carried out in small and large groups; workbook exercises; quizzes; games and role playing.

The Empirical Evidence

Stallard, Simpson, Anderson and Goddard (2008) evaluated the effectiveness of FRIENDS through conducting a one-year longitudinal study where measures of self-reported anxiety and self-esteem were collected from participants at three time points (programme end; 3-months later; 12-months later). The researchers highlighted the long term preventative effect of the programme when illustrating their findings that the lower incidence rates of self-reported anxiety and increases in self-esteem observable immediately after implementation were maintained 3 and 12 months later (Stallard et al., 2008).

In Practice: Mindfulness in Schools

A less conventional approach throughout schools is the concept of mindfulness training in the classroom. Claxton (2008) argues for the importance of fostering social and emotional skills in the early years but states that these skills are more appropriately described as ‘habits of the mind’. By introducing the SEAL curriculum, Claxton believes that the government has taken a huge step in the right direction in terms of properly defining what these habits of the mind are and how they can be trained and fostered in the classroom (Claxton, 2008). Writing for the psychologist magazine, Dan Jones asks the question of whether ‘habits of the mind’ can actually enhance the wellbeing and resilience of school children – a question that authors such as Weare (2010) would point towards mindfulness to answer ‘yes’ to. According to Weare (2010) “mindfulness could really help teachers get to the heart of the skills SEAL tries to nurture…”.

Aims of Mindfulness

Mindfulness is described as a ‘mode of being’ that aims to exert non-judgemental attention over one’s own thoughts at a current moment in time or over their emotional experience of the present moment (Jones, 2008). Responding non-judgementally to the contents of one’s mind, the premise is that these responses are less likely to trigger negative emotions or behaviours such as distress (Jones, 2008). As well as this, Huppert (2011) proposes 5 main benefits of mindfulness.

The Application: A State of Mindfulness - How & Why?

Does a state of mindfulness appeal to you? Read more about it here or watch this tutorial and try it out for yourself!

Huppert (2011) argues from a state of mindfulness comes five main benefits ofincreased sensory awareness; greater control over cognitions; enhanced regulation of emotions; acceptance of all thoughts and feelings and the ability to regulate personal attention. It is these capacities that authors base their proposal for the effectiveness of mindfulness in schools on and its relation to the SEAL curriculum. Jones (2011) argues that the enhanced self-awareness and ability to regulate emotional responses that mindfulness produces is beneficial for individuals in the face of adversity but also in their relationships with others. Weare (2011) supports this relationship context further by stating that if an individual possess greater control over his/her general impulses their relations with others will be enhanced overall.

Empirical Evidence

Throughout the past two decades the benefits of mindfulness as previously discussed have been consistently reported in clinical and non-clinical contexts (Baer, 2003; Greeson, 2009). However, the vast majority of these studies have been conducted with adults. Today, a body of evidence is beginning to build up on the effectiveness of mindfulness in and out of the classroom (Burke, 2010).

In 2010 Huppert & Johnson produced the first peer reviewed paper on the use of mindfulness training within the school setting. The researchers developed a 4 week mindfulness programme, consisting of 40 minute sessions that would be delivered once a week through religious education classes. Implementing this through 2 schools and over 173 14/15 year olds, Huppert & Johnson identified an overall increase in wellbeing (as measured by an accumulation of mental wellbeing; resiliency style and mindfulness measures) in pupils who underwent mindfulness training compared to controls. Further, it was found that this effect was ‘dose-dependent’ in that the more mindfulness training had been undertaken, the greater wellbeing scores were effected.

Emotional intelligence (EI), as previously stated; is one area of research that contributed to the introduction of Social and Emotional learning in the classroom throughout the UK. As well as education, EI has been linked to effectiveness in the workplace. Emotional Intelligence concepts overlap with positive psychology in terms of positive emotion focus.

Theoretical Approach

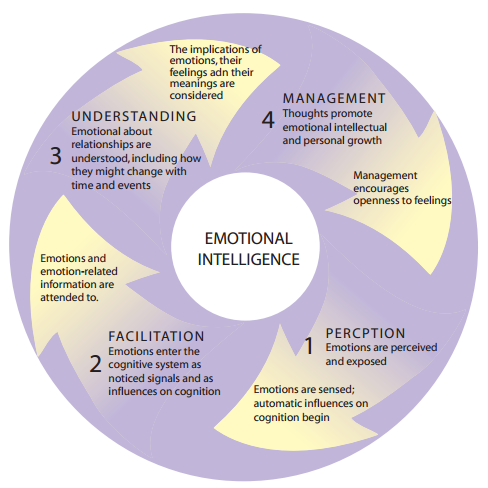

Emotional Intelligence is defined by Salovey Caruso & Mayer (2004) as “the ability to accurately perceive, access and generate emotions, assist thought processes and reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth. Salovey and Co. propose four main components of EI through their Abilities Model which the diagram below details.

In the classroom, the premise is that becoming emotionally intelligent will allow a child to form good quality and lasting relationships; regulate their emotions; impulses and attention and appropriately deal with hardships and setbacks (Mavroveli & Sanchez-Ruiz, 2011). In the workplace, it is proposed that EI will increase positive work outcomes by facilitating personal achievement (Goleman, 1995; Dulewicz & Higgs, 2000).

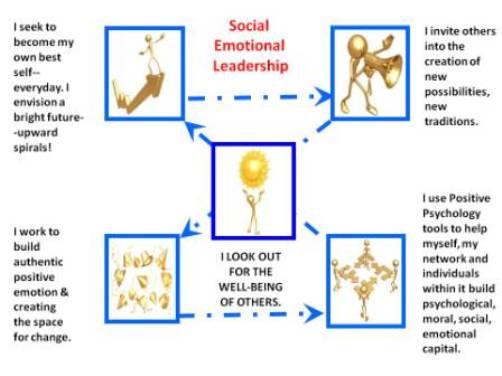

Practical Application: Emotional Intelligence in Workplace Leadership

Numerous organizational studies have supported the proposed effectiveness of emotional intelligence specifically in the context of leadership development programmes.

Empirical Evidence

Riggio and Reichard (2008) evaluated an earlier framework of their own that looked at the emotional abilities of leaders in three main ways; emotional expressiveness;emotional sensitivity; emotional control.

Reviewing broader literature and results from their own leadership development programmes, the researchers propose that:

- Positive emotionally expressive leaders are perceived as more charismatic (Bass, 1990; Riggio, 1987) and are generally more effective (Groves, 2006).

- Positive emotionally expressive leaders create positive affect in a team that is then related to increased group motivation (Barasade, 2002) and better task performance (Isen, 2004). Fredrickson (2009) say that these positive emotions go on to spark emotional wellbeing.

- Emotionally sensitive leaders have better relationships with group members.

- Emotionally sensitive leaders are more effective at picking up on negative emotions throughout group members.

- Emotionally controlled leaders project a more calm impression throughout times of stress and are generally more effective during stressful periods.

Riggio and Reichard (2008) argue that these emotionally intelligent skills are ones that can be strengthened and developed throughout leadership programmes and should, in fact, be an essential component of these.

Read more about emotional intelligence here.

More Positive Psychology in the Workplace: Psychologic Capital

Positive psychology is not only beneficial to employees in a position of leadership within the workplace. Luthans (2008) describes the concept of Psychologic Capital that consists of the psychological strengths of hope resilience optimism and efficacy and their effectiveness within the workplace for all employees.

Theoretical Approach

Psychologic Capital is derived from the notion of Human Capital which focuses on the positives that individuals bring to the workplace – for example – experience, education, skills, knowledge and ideas. Similarly to Human Capital and alike Emotional Intelligence, Psychologic Capital directly relates topositive emotions (Froman, 2009). Froman (2009) suggests that it is an imperative component to an organization if they are to thrive in today’s declining global economy.

Aims of Psychologic Capital

To foster and develop the strengths of hope resilience optimism and efficacy amongst employees. These strengths will enhance emotionality throughout employees and hence, create advantages for the organization as a whole.

Empirical Evidence

Investigations into the effectiveness of Psychologic Capital throughout the workplace have obtained various encouraging results concerning its relationship with job satisfaction and performance (Luthans et al., 2007) commitment to the organization (Youssef & Luthans, 2007) and absenteeism amongst employees (Avey et al., 2006).

Mind Food Science: Eating Well Makes Us Feel Good

Jacka et al (2012) looked at the relationship between the quality of everyday diet and common mental disorders: depression and anxiety. Adolescents scoring higher on a measure of Healthy diet were less likely to report symptomatic depression, compared to those with an increased consumption of processed and ‘junk’ foods who were more likely to report depression.

What Can You Do?

An article on How to Lose Weight Positively tells you not to view your diet or exercise as a negative chore: this will decrease your chance of success. There is a significant correlation between healthiness and happiness (Borghesi & Vercelli, 2010), so goes the phrase “healthy body, healthy mind”.

“We have control over our destiny – what we put in our body has a direct relationship to what we express. It is further evidence that we are holistic beings – that everything we do effects everything.”

The Real “Happy Meal”

A balance of healthy carbs, protein, and fats, gives your body what it needs for long-lasting energy and a good mood. A high intake of vegetables, fish, fatty acid supplements, and mineral supplements correlated with levels of happiness. Evidence from dietary intervention studies indicates an improvement of quality of life and mental health-related variables through healthy diets, particularly the Mediterranean one (Halyburton et al, 2007). The Mediterranean diet has been linked to a low levels of depression (Popa & Ladea, 2012). A study by Muñoz et al (2009) found that self-perceived mental and physical health was directly associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet in men and women.

Mediterranean Diet How To:

Mediterranean Diet How To:- High consumption of breads, pasta, rice, couscous, polenta, bulgur and potatoes

- High consumption of fruits (3-4 pieces a day), legumes and vegetables (5 different varieties)

- Moderate amounts of grilled and steamed fish

- Moderate amounts of olive oil - consumed with fresh vegetables and on salads

- Small portions of lean red meat with no visible fat, new fashioned pork

- Alcohol in small amounts

- Regular physical activity

- High intake of antioxidants

Typical Day on the Diet

Breakfast | Two slices of wholemeal bread with olives and fresh fruit. |

Lunch | Chickpea soup with tomato/cucumber salad and two slices of wholemeal bread. |

Dinner | Grilled fish with baked lemon potatoes and chicory salad. 120ml glass of red wine |

Snacks | Dried apricots and figs, including fresh fruit. A handful of roasted (unsalted) almonds. |

In sum, self-perceived mental and physical health function was directly associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet in both sexes (Muñoz et al, 2009): why not give it a go?

Yoga is a system of physical and mental practices that originated in India around 3000 years ago (Kraftsow, 1999). Modern forms of yoga are based on these ancient teachings, and although there are many, varied schools of practice, the standard components (Kirkwood et al, 2005; Pilkington et al, 2005) include:

- · Specific postures (asanas),

- · Breathing exercises (pranayamas), and

- · Meditation (dhyana)

Yoga practices are designed to enable development and integration of the human body, mind, and breath to produce structural, physiological, and psychological effects (Joshi et al, 2012). The aims of yoga are the development of:

- · Strong and flexible body free of pain,

- · Balanced autonomic nervous system with all physiological systems, e.g., digestion, respiration, endocrine, functioning optimally;

- · Calm, clear, and tranquil mind.

- · Overall quality of life (Pilkington et al, 2005).

Yoga can enhance sleep quality. Studies have shown enhanced slow wave sleep and improved Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep in those practicing yoga (Joshi et al, 2012).

Studies have demonstrated a 27% increase in brain GABA levels after a yoga class in experienced yoga practitioners (Streeter et al, 2007). It is suggested that the practice of yoga should be explored as a treatment for disorders with low GABA levels such as depression and anxiety disorders

The neurotransmitter changes that occur during meditative practices contribute to the amelioration of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Mohandas, 2008) following at least one yoga session (Lavey et al, 2005). Research has demonstrated that long-term yoga practitioners have lower mental disturbances, anxiety, anger and fatigue scores in the Profile Of Mood State (POMS) test in comparison to non-experienced participants.

Small, easy, everyday changes you can make which have been proven to ameliorate symptoms of anxiety and depression, and increase happiness.

“Happiness is not something ready made. It comes from your own actions.”

1. Count Your Blessings

Every night write three things you are grateful for and a causal explanation for each (Seligman et al, 2005). Studies have shown that those on the gratitude-outlook had heightened measures of wellbeing and that conscious focus on blessings has emotional (Emmons et al, 2003) and interpersonal benefits (Algoe & Haidt, 2009).

By making a gratitude list every day, you retrain your brain to notice the positive and for this to be a more automatic pattern.

2. Loving-Kindness Meditation

Research by Christine Carter PhD (2010) showed that participating in loving-kindness meditation for five minutes a day increased people’s experiences of positive emotions. It allows people to become more satisfied with life and ward off depression by increasing sense of purpose, and looking out for a stronger social support system.

This easily implemented technique increased feelings of social connection and positivity toward new people and can help to decrease social isolation (Hutcherson et al, 2008). Research even shows that loving-kindness meditation "changes the way people approach life" for the better. (Carter, 2010)

3. Spring Clean

Jeffery Rossman (2010) found that regardless of the activity, when we are focused on the task at hand, we are more likely to feel happy than if they were distracted. The importance of mindfulness, an intentionally generated state of focused attention that also boosts happiness. Living mindfully in the present re-wires our brains for joy.

By focusing on “unitasking” on something like spring-cleaning, we all have the potential for clear-minded happiness, but in our high-distraction culture, many of us have to work at developing it.

A little window spray and spending some time returning everything to its rightful place replaces that stress with bliss. Other tasks that encourage mindful awareness during everyday activities, such as making tea, washing dishes or clothes, cleaning house, or taking a bath, can help to increase left-prefontal cortex activity: the part of the brain most active in happy people (Harmon-Jones et al, 2001)

4. Have a Cup of Tea

Traditionally, tea was drunk to improve blood flow, eliminate toxins, and to improve resistance to diseases (Balentine et al, 1997). Tea, associated with lifestyle and nutritional habits, gave tea consumption rituals in China, Japan, and England a unique place between a mere beverage and a social function where food is closely associated with a state of mind.

Take a few minutes and go make a cup of tea: have some ‘me’ time. Sit back, enjoy, and spend five minutes with no disruptions. Studies show that 6 weeks of tea consumption leads to lower post-stress cortisol and greater subjective relaxation and can aid stress recovery. (Steptoe et al, 2007).

A tea break at work is associated with a high social support, time to express feelings, increased resilience, and relaxation for women (Steptoe & Wardie, 1999).

5. Get Some Fresh Air

Fresh air makes you happier. By inhaling more oxygen, you are taking in more serotonin which can significantly lighten your mood and promote a sense of happiness and well-being (Rodiek, 2002). By making you feel more refreshed and relaxed, getting outside for at least a few minutes a day has been found to be spirit lifting (Marcus, 2008).

For centuries, nature has been considered to have healing potential. Why not also have plants or other nature elements incorporated into your home and work settings, which has shown to improve the atmosphere for patients and visitors in healthcare settings (Lewis, 1996).

6. Write Someone a Letter

In this digital age, the art of letter writing seems to have passed. Why not get out your paper and pens and write a heart-felt letter to a friend expressing your gratitude, and post it the old-fashioned way.

Taking the time out to think about someone you love produced a positive affect increase (Watkins et al, 2003) by the fact that putting one’s feeling and thoughts of gratitude on paper has real benefits after the pen leaves the paper (Toepfer & Walker, 2009).

7. Call a Friend

Pick up the phone and call a friend you haven’t seen in a while. Talk about something completely irrelevant and have a good laugh. Reconnecting with old friends reminds us of where we came from and allows us to take stock of where we’re heading, and how far we’ve come.

8. Tell a Joke

“Laughter is the best medicine”

Playful behaviours, such as humour, day-dreaming, fantasy, and make believe resulted in increased positive moods (Singer & Switzer, 1980). The benefits of laughter are plentiful, having both psychological and physiological effects. Laughter reduces stress hormones and improves mood (Zand, Spreen, and LaValle, 1999), and shows significantly greater improvement in mood than smiling (Charles & Schaefer, 2002).

What’s more, laughing is contagious (Provine, 1992), thus helps to promote socialization. By lubricating social interaction, easing tensions and competition, maintaining group identities, and coordinating the emotions and behaviors of a group (Gervais & Wilson, 2005), why not spread some happiness?

Seeing babies laugh, you can’t help have a smile on your face.

9. Identify Your Strengths

Identify your strengths using the VIA assessment tool. Learning what your personal character strengths are allows you to reach your full potential with your work, your family, and your relationships.

According to VIA research, a strengths- based approach to life is:

- Honest (acknowledges problems, but doesn't get lost in them);

- Positive (focuses on what is best and good);

- Empowering (encourages and advances the individual);

- Energising (uplifts and fuels the person);

- Connecting (brings the person closer to others, aiding in mutual connection).

Using your strengths in a novel way was found to made people happier up to 6 months later (Seligman et al, 2005), demonstrating that five minutes everyday can have great long term benefits.

10. Daily Hugs

Hugs contribute to health and healing according to The Hug Therapy (Keating, 1983). This book argues that hugging feels good, dispels loneliness, overcomes fears, and builds self-esteem. Anyone can be a “hug therapist”, arguing that it is a “mutually healing process”.

Hugging produces oxytocin, dubbed “the cuddle hormone,” by Dr. George Vaillant (2008). Oxytocin is the hormone responsible for all sorts of interpersonal bonding and attachment between parents and children or romantic partners.

Researchers still remain sceptical of positive psychology as a science, even though they are amazed at how fast the movement has grown (Gable and Haidt, 2005). There have been several criticisms on positive psychology, in many areas and in different aspects. Notably, criticism is composed around: the consequences of a positive-focused psychological science; its methods of measurement; the clash with humanistic psychology and issues with purely positive attitudes.

1) Positive versus Negative

2) Measurement Controversies

Even though positive psychology is proving to be a popular science, they are still those that believe it is not a real science as happiness is difficult to specifically measure. Because of this, some have criticised and questioned whether positive psychology can truly become an evidence based practice. However, Martin Seligman and colleagues believe that the word ‘happy’ is scientifically unwieldy (Duckworth, Steen and Seligman, 2005). Therefore for the purpose of serious study, the term must be dissolved into at least three distinct and better-defined routes to ‘happiness’: 1) positive emotion or pleasure, 2) engagement and 3) meaning. Therefore when using the word ‘happiness’, they are labelling the overall aim of the positive psychology endeavour. Martin Seligman and colleagues accepted the fact that measurements of general happiness do indeed exist but they do not allow researchers to make finer distinctions in the three forms of happiness. They designed interventions that could do so, creating the Steen Happiness Index which is structured to be sensitive to week-by-week changes in happiness levels. Pilot research on this new measure has shown that scores converge substantially on other measures of happiness (Seligman et al, 2005) and has been used extensively in research (Schiffrin and Nelson, 2010).

3) Humanistic Psychology

Humanistic psychologists have made a fair amount of criticism, stating that positive psychology aims to discredit humanistic psychology. It is believed that positive psychology has aimed to distance itself as a new movement despite the fact the two sciences tend to overlap in thematic content as – for the last half-century – humanistic psychology has focused its attention on what it means to flourish as a human being. In fact, humanistic psychology is the field most identified with the study and promotion of positive human experience (Duckworth, Steen and Seligman, 2005). Humanists such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow have been credited as the ‘ancestors’ of the positive psychology movement. It was in fact Abraham Maslow who coined the phrase ‘positive psychology’ more than forty years prior to Seligman’s use of the term for his own work and that of others (Robbins, 2008). Yet some believe that positive psychology specifically distinguishes itself as a new movement, which is the source of all this criticism. But in fact, positive psychologists have constantly credited humanistic psychology as a ‘contemporary cousin’ and for pioneering the territory of positive psychological research and practice.

4) Positive Attitude Issues

Notable criticisms have been made by Lazarus (2003) pointing out certain features of the movement are found to be troubling. He speaks of positive thinking as an ability, in order to emphasise that not everyone is able to gain its potential benefits for themselves. There may be a significant number of people who could benefit from it, yet they cannot change because of ingrained habits of thought. There is therefore a major issue with the concept of mental change in adults as it has been argued that once an individual reaches adulthood, there is considerable stability but one must still allow for modest change (Caspi and Roberts, 2001). For there to be major personality change in a stable adult, it may require a trauma, a personal crisis or a religious conversion. Experts cannot agree on the prospect that for change on the basis of evidence that, unfortunately, is not clear even when it comes to personality changes sought in psychotherapy (VandenBos, 1996). This issue is therefore still in discussion amongst researchers.

What's the Verdict?

Positive psychology is a relatively new science, despite its growing popularity. There are still questions attached to the science from those who remain sceptical. There have been adaptations to positive psychology where it is has been converted to an internet intervention which has been shown to be influential. The fact that internet based interventions of positive psychology can be effective without any type of therapeutic alliance only goes to show the strength of the ingredients of the treatment (Seligman et al, 2005). There is indeed the possibility that interventions of positive psychology will not make people lastingly happy (Seligman et al, 2005). We can’t deny however that positive psychology has made a difference to negative symptoms.

Further Reading on Criticism of Positive Psychology

Linley, P.A., Joseph, S., Harrington, S. and Wood, A.M. (2007). Positive psychology: past, present and (possible) future. The Journal of Positive Psychology: dedicated to furthering research and promoting good practice 1 (1), p3-16Lazarus, R.S. (2003). Does the positive psychology movement have legs? Psychological Inquiry 14 (2), p93-109

Seligman, M.E.P., Steen, T.A., Park, N. and Peterson, C. (2005). Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist 60 (5), p410-421References

Algoe, S. B., & Haidt, J. (2009) Witnessing excellence in action: The ‘other-praising’emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. The Journal of Positive Psychology, vol.4, pp.105-127.

Avey, J. B., Patera, J. L., & West, B. L. (2006). The implications of positive psychological capital on employee absenteeism. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 13, 42–60.

Baer, R.A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10 (2), 125–143.

Balentine, D.A., Wiseman, S.A. & Bouwens, L.C. (1997) The chemistry of tea flavonoids,Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., vol.37, pp. 693–704

Bandura, A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. San Fransisco, CA: Freeman

Beattie et al, (2011), Investigating the possible negative effects of self-efficacy upon golf putting performance, Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12, 434-441

Carter, C. (2010) Raising Happiness: 10 Simple Steps for More Joyful Kids and Happier Parents, Random House Publishing Group

Borghesi, S. & Vercelli, A. (2012) Happiness and health: two paradoxes.Journal of Economic Surveys, vol.26, pp.203-233

Burke, C.A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 133–144

Caspi, A., & Roberts, B.W. (2001). Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry, 12, p49–66

Charles, C.N., & Schaefer, C. (2002) Effects of laughing, smiling, and howling on mood. Psychological reports, vol.91, pp.1079-1080

Chroni et al (2008), Self-Talk: it works, but how? Development and preliminary validation of the functions of Self-Talk Questionnaire, Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 12, 10-30

Claxton, G. (2008). What’s the point of school? Rediscovering the heart of education. Oxford: OneWorld

Coleman, J. (2009). Wellbeing in schools: Empricial measure or politician’s dream? Oxford Review of Education, 25(3), 12.

Compton, W. C., (2005) An Introduction to Positive Psychology. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

De Botton, A., (2005) Religion For Atheists. London, UK: Penguin Group

Department for Children, Schools and Families [DCSF]. (2008). Improving the mental health and psychological well-being of children and young people: national child and adolescent mental health service review.

Department for Education and Skills (2004) Every child matters (London, DfES).

DfES (2005) Excellence and Enjoyment: Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning. London: The Stationary Office.

Duckworth, A.L., Steen, T.A. and Seligman, M.E.P. (2005). Positive Psychology in Clinical Practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 1,p629-651

Dulewicz, V., & Higgs, M. (2000). Emotional intelligence: A review and evaluation study. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15, 341–372.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotion learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405-432.

Ekman, P. B. (2005). Buddhist and Psychological Perspectives on Emotions and Well-Being. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 14, 59-63.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity. New York: Crown

Froman, L. (2010). Positive Psychology in The Workplace. Journal of Adult Development, 17, 59-69.

Gable, S.L. and Haidt, J. (2005). What (and Why) is Positive Psychology? Review of General Psychology 9(2),p103-110

Galanis et al (2011), Self-Talk and Sports Performance: A Meta-Analysis, Perspectives of psychological science, 6, 348-356

Gervais, M. & Wilson, D.S. (2005) The Evolution and Functions of Laughter and Humor: A Synthetic Approach, The Quarterly Review of Biology, vol.80, pp. 395-430

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam

Goleman, D. (1996) Emotional intelligence (London, Bloomsbury).

Greeson, J.M. (2009). Mindfulness research update 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14 (1), 10–18.

Halyburton A.K., Brinkworth, G.D., Wilson CJ, et al. (2007) Low- and high-carbohydrate weight-loss diets have similar effects on mood but not cognitive performance. Am J Clin Nutr, vol.86, pp.580–587

Harmon-Jones, E., & Sigelman, J. (2001) State anger and prefrontal brain activity: evidence that insult-related relative left-prefrontal activation is associated with experienced anger and aggression. Journal of personality and social psychology, vol.80, pp.797

Hatzigeorgiadis et al, (2006), Instructional and motivational self-talk: an investigation on perceived self-talk functions, Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 3, 164–175

Hefferon, K. and Boniwell, I. (2011) Positive Psychology Theory, Research and Applications. Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill.

Held, B.S. (2004). The Negative Side of Positive Psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 44 (9), p8-46

Huppert, F.A. & Johnson, D.M. (2010). A controlled trial of mindfulness training in schools: The importance of practice for an impact on well-being. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5 (4), 264-274.

Hutcherson, C.A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008) Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion; Emotion, vol.8, pp.720

Isen, A. M., & Reeve, J. (2005). The influence of positive affect on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Facilitating enjoyment of play, responsible work behaviour, and self-control. Motivation and Emotion, 29, 295–323.

Jacka, F.N., Rothon, C., Taylor, S., Berk, M. & Stansfeld, S.A. (2012) Diet quality and mental health problems in adolescents from East London: a prospective study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, pp.1-10

Jones, D. (2011). Mindfulness in Schools In The Psychologist Magazine. 24(10) 736-739.

Joshi, A., & De Sousa, A. (2012) Yoga in the management of anxiety disorders. Sri Lanka Journal of Psychiatry, vol.3, pp.3-9

Keating, K. (1994) The hug therapy book. Hazelden Publishing & Educational Services.

Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Tuffrey V, Richardson J, Pilkington K. (2005) Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review of the research evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol.39, pp.884–91

Kraftsow G. (1999) Yoga for Wellness. New York: Penguin Compass

Lavey, R., Sherman, T., Mueser, K.T., Osborne, D.D., Currier, M. & Wolfe, R. (2005) The effects of yoga on mood in psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, vol.28, pp.399-402

Lazarus, R. S. (2003). Does the Positive Psychology Movement Have Legs? Psychological Inquiry 14 (2), p93-109

Linley, P.A., Joseph, S., Harrington, S. and Wood, A.M. (2007). Positive psychology: past, present and (possible) future. The Journal of Positive Psychology: dedicated to furthering research and promoting good practice 1(1), p3-16

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007).Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541–572

Luthans, F., Norman, S. M., Avolio, B. J., & Avey, J. B. (2008). The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate-employee performance relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 219–238

Marcus, S.M. (2008) Depression during pregnancy: rates, risks, and consequences—Motherisk Update, Can J Clin Pharmacol., vol.16, e15-e22.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 197–215.

Miller, A. (2008). A critique of positive psychology – or ‘the new science of happiness’. Journal of Philosophy of Education 42 (3-4), p591-608

Mohandas E. (2008) The Neurobiology of Spirituality. Mens Sana Monographs, vol.6, pp.63-80

Muñoz, M.A., Fíto, M., Marrugat, J., Covas, M.I., & Schroder, H. (2009) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with better mental and physical health.British Journal of Nutrition, vol.101, pp.1821

Mustard, F. (2008). Investing in the early years: Closing the gap between what we know and what we do. Adelaide: Government of South Australia.

Pawelski, J. O., and Gupta, M. C., (2009) Utilitatianism. In S. J. Lopez, ed. (2009) The Encylopedia of Positive Psychology. Chichester, UK:Wiley-Blackwell, pp.998-1001.

Peterson C. (2006). A Primer in Positive Psychology. New York : Oxford UniversityPress

Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Richardson J. (2005) Yoga for depression: the research evidence. Journal of Affective Disorders, vol.89, pp.13–24

Provine, R. R. (1992) Contagious laughter: Laughter is a sufficient stimulus for laughs and smiles. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society.

Rasmussen, H.N., Scheier, M.F. and Greenhouse, J.B. (2009). Optimism and Physical Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 37,p239-256

Riggio, R. E., & Reichard, R. J. (2008). The emotional and social intelligences of effective leadership. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23,169–185.

Robbins, B.D. (2008). What is the Good Life? Positive Psychology and the Renaissance of Humanistic Psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist 36 (2), p96-112

Rodiek, S.D. (2002) Influence of an outdoor garden on mood and stress in older persons. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, vol.13, pp.13-21

Rossman, J. (2010) The Mind-Body Mood Solution: The Breakthrough Drug-Free Program for Lasting Relief from Depression

Schiffrin, H.H. and Nelson, S.K. (2010). Stressed and Happy? Investigating the Relationship Between Happiness and Perceived Stress. Journal of Happiness Studies 11, p33-39

Seligman, M. E. P., (2003) Authentic Happiness. London, UK: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Seligman, M.E.P., Steen, T.A., Park, N. and Peterson, C. (2005). Empirical Validation of Interventions.American Psychologist 60 (5), p410-421

Singer, J. & Switzer, E. (1980) Mind-play: The Creative Uses of Fantasy. Toronto: Prentice-Hall

Smith, T., McCullough, M., and Poll, J. (2003). "Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events". Psychological Bulletin 129, 614–36

Stallard, P., Simpson, N., Anderson, S. & Goddard, M. (2008). The FRIENDS emotional health prevention programme: 12 month follow-up of a universal UK school based trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17, 283-289.

Steptoe, A. & Wardle, J. (1999) Mood and drinking: a naturalistic diary study of alcohol, coffee and tea,Psychopharmacol, vol. 141, pp. 315–321

Steptoe, A., Gibson, E.L., Vounonvirta, R., Williams, E.D., Hamer, M., Rycroft, J.A. &

Streeter, C.C., Jensen, J.E., Perlmutter, R.M., Cabral, H.J., Tian, H, Terhune, D.B., Ciraulo. D.A., Renshaw, P.F. (2007) Yoga Asana sessions increase brain GABA levels: a pilot study. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, vol.13, pp.419-26

Taimini, I.K. (1986) The Science of Yoga. Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House

Taylor (2009), Sports: Building Confidence: Part II, Psychology Today, Retrieved 5/2/13, http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-power-prime/200909/sports-building-confidence-part-ii

The Office for National Statistics Mental health in children and young people in Great Britain (2005).

Toepfer, S., & Walker, K. (2009) Letters of gratitude: Improving well-being through expressive writing. Journal of Writing Research, vol.1, pp.181-198

Tracey et al (2011), Benefits and Usefulness of a Personal Motivation Video: A Case Study of a Professional Mountain Bike Racer, Applied sport psychology, 23, 308-325

Vaillant, G. (2008) Spiritual Evolution: A Scientific Defense of Faith. New York: Broadway Press

VandenBos, G. R. (1996). Outcome Assessment of Psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 51(10)

Wardle, J. (2007) The effects of tea on psychophysiological stress responsivity and post-stress recovery: a randomised double-blind trial, Psychopharmacology, vol.190, pp.81-89

Watkins, P.C., Grimm, D.L., & Kolts, R. (2004) Counting your blessings: Positive memories among grateful persons. Current Psychology, vol.23, pp.52-67

Weare, K. (2004) Developing the emotionally literate school (London, Paul Chapman).

Weare, K. (2010). Promoting mental health through schools. In P. Aggleton, C. Dennison, & I. Warwick (Eds.), Promoting health and well-being through schools (pp. 24–41). London: Routledge.

Zand, J., Spreen, A.N. & LaValle, J.B. (1999) Smart medicine for healthier living. Garden City Park, NY: Avery

Zinsser et al, (2001), Cognitive techniques for building confidence and enhancing performance. Applied sport psychology: Personal growth to peak performance, 284-311

Moodle Docs for this page

Moodle Docs for this page