Where your group creates its page(s)

Wiki

Altruism, Eudaimonia and Meaning in Life

"Altruism is intelligent selfishness."

The Dalai Lama

Table of Contents

- History and Cultural Connections

- Key Papers and Suggested Reading

- Eudaimonia vs. Hedonism

- Practicing Eudaimonia

- Benefits and Potential Clinical Applications

- Criticisms and Limitations

- "Promising" the "secret" of well-being

- Key Points

- Reference

Introduction

Would you rather...

-... have sex purely to get pleasure OR have sex with someone you love ?

-...go to a big party and get drunk OR stayed at home writing out your goals for the future ?

-...buy a piece of jewellery or electronics just for yourself OR gave money to a person in need ?

The question of what makes us happy has fascinated psychologists for a long time. Is happiness simply a matter of feeling pleasure for pleasures sake.Or is it the case that to be happy, pleasure is important but not enough: meaning is required.In that sense, doing things for other people seems to be an important part.

Eudaimonia is a conjunction of two Greek words: happiness and flourishing. Most psychological literature refers to eudaimonic activity as acting towards a goal because it is in line with personal values such as relatedness or personal growth (Ryff & Singer, 1998). In contrast, hedonism the seeking of pleasure for no other reason than that it is pleasurable. Altruism, an unselfish concern towards others - form of eudaimonic activity, is usually the focus of eudaimonic research.

History and Cultural Connections

The concepts of altruism and eudaimonia have been discussed and questioned extensively throughout history, from Aristotelian philosophy all the way to modern psychological interpretations. Many have argued that when seeking meaning in life, altruistic behaviour plays a crucial role.

Ancient Greek Philosophy

The view of eudaimonia as discussed by Aristotle refers to the idea that true happiness is found in doing what is worth doing, leading to the realisation of one’s true potential and an optimal state of well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2001). This idea stands in contrast to the hedonic approach to well-being, which defines it as maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain (Steger et al, 2008). The philosopher Aristippus argued that happiness and well-being is simply the totality of one’s pleasure, or “hedonic moments” (Ryan and Deci, 2001). In that sense, the eudaimonaic view and the hedonistic view are opposing in their conclusions. The eudaimonaic approach requires striving for things in life that are inherently worthwhile while the hedonistic approach emphasizes simply feeling good. Research tends to show that eudaimonaic activity develops enduring well-being more than activity focusing simply on obtaining pleasure (Steger et al, 2008).

Darwinism

Though philosophers may have argued that altruistic behaviour is eudaimonaic and leads to a state of well-being, altruism plays a different role in Darwin’s evolutionary theory. Darwin argues that behaving selfishly has traditionally increased one’s chances of survival, so according to the principles of natural selection, it would be maladaptive over evolutionary time for altruism to prevail (Carter, 2005). This makes altruism as a concept incompatible with evolutionary theory. However, arguments have since been presented concerning the possible long-term stability of a society of altruists (Carter, 2005) and the potentially evolutionary benefits of altruistic behaviour. Darwin’s theory, though it considers the likelihood of altruistic traits being preserved in the gene pool, does not consider its potential adaptive effects on happiness and well-being.

Modern Thought

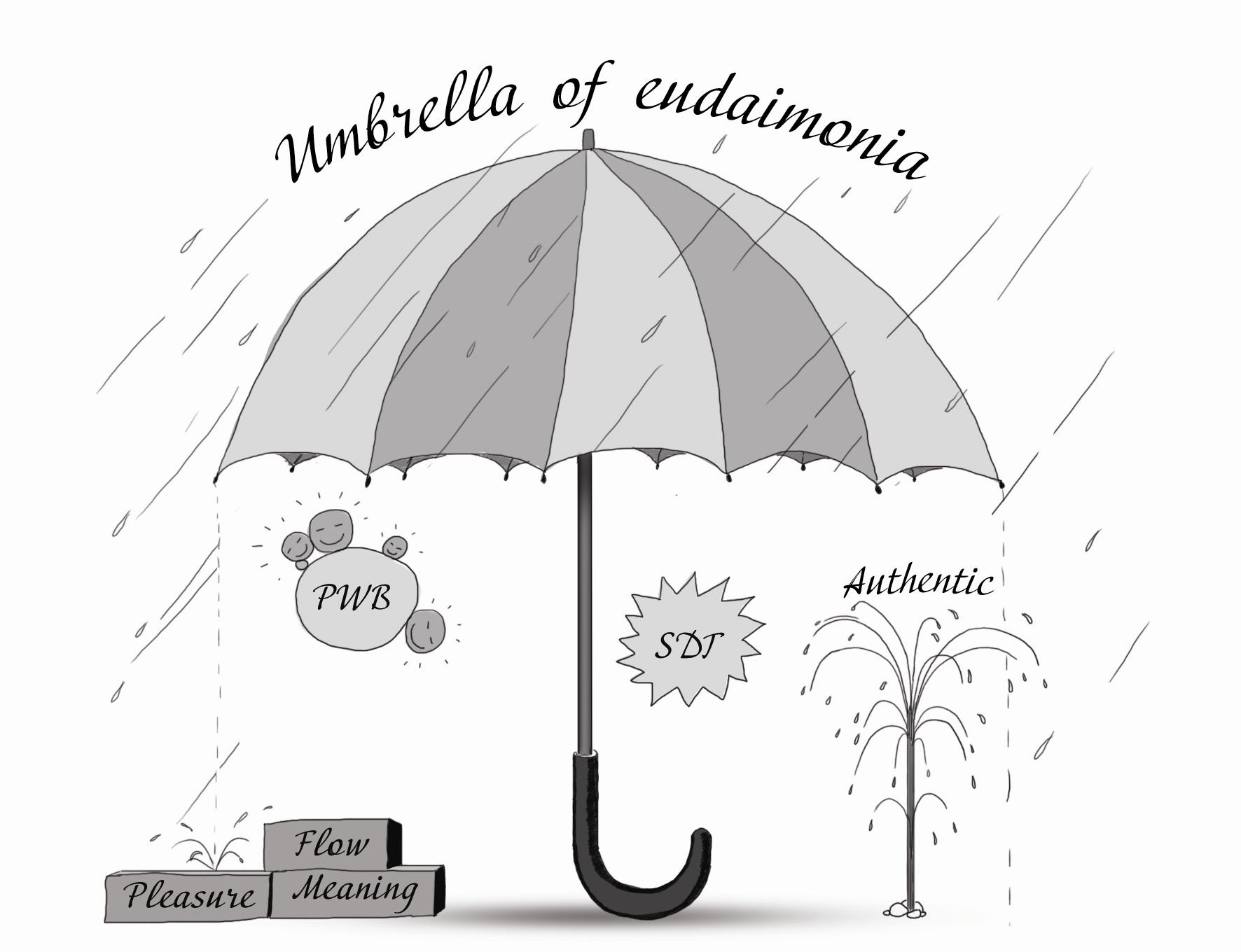

A variety of other philosophical arguments and psychological research studies have cited altruism and eudaimonia as factors in finding meaning. Many modern theories, such as the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the Psychological Well-Being theory, are centered around a variety of specific factors that maximize the capacity for well-being, such as personal growth, self-acceptance, and purpose in life (Ryff and Singer, 1998). Many religious, spiritual, or other “intrinsically meaningful” activities that are consistent with one’s beliefs and values have also been correlated with happiness and well-being (Waterman, 1993). A lot of today’s psychological research focuses less on the classical historical theories, such as the previously discussed Aristotelian philosophy and Darwinism, and more on the modern factors and culturally relevant behaviours that contribute to well-being.

Key papers and suggested readings

If you are new to the area of eudaimonaic theory within positive psychology, then Waterman’s (2008) article provides a good review of how far it has come over the past few years. The article itself is a response to various criticisms on the research into eudaimonaic theory (Kashdan et al, 2008).

The article covers the main definitions central to the theory, as well as some of the key criticisms you are likely to encounter when delving into the topic. The article is especially useful when considering the similarities and differences of eudaimonia and hedonism (as well as well-being), which is central to achieve a good understanding of the topic.

Steger et al (2008)

Intro

This study focuses on the whether eudaimonaic and hedonic behaviours result in well-being. The rationale behind the study is that although there are many claims that eudaimonia results in happiness, but, there have been no subjective measures as to whether this is the case.

Daily diary entries (over 3 or 4 weeks) are used to assess an individual’s well-being. Through diary entries there are four factors were measured: life satisfaction, meaning in life, and positive and negative effect.

Results

After an analysis of the diary entries, there was a clear positive correlation between engaging in eudaimonaic behaviours and well-being. For hedonic behaviours, there was a correlation for positive effect, but not for well-being. However, we must be wary that that a correlation does not mean causation.

Conclusion

A major criticism of this study and perhaps more so now in light of more recent research into eudaimonic theory of happiness, is the assumption that eudaimonic and hedonic behaviours are mutually exclusive. Although they do take into account that both behaviours are a means to achieve happiness, they do not give much thought to the difficulties in defining the two terms, and considering the overlap between the two.

A potential problem with this study is also the use of the daily diaries. Although it is a novel approach to collecting subjective experiences of eudaimonic behaviour, this also lends itself to various problems. We cannot assume that the same subjective experiences between participants results in the same feelings of well-being. This raises questions as to whether there is a valid measure of eudaimonaic behaviour, and whether such a scale holds reliability.

Waterman et al (2010)

A more recent study has actually approached the question of validity. Waterman et al (2010) issued the Questionnaire for Eudaimonaic Well-being to a diverse and large sample. They found that internal validity was high and that the varying demographics of the sample only accounted for a small percentage of variability. The conclusion was that this scale was an effective tool for the measure of eudaimonaic well being. This is good news for future research into the assessment of eudaimonaic well-being. If those researching the area begin to adopt this measure, and results are found to be consistent across different populations, the scientific advancement of the eudaimonaic theory of happiness can only be better off for it.

Eudaimonia vs Hedonism

Currently there is huge controversy between eudaimonia vs hedonism as two opposing views on what can make an individual truly happy. The next section of the wiki will look at hedonism in order to better understand the difficulty one chooses when having to decide whether to stick to eudaimonia or hedonism.

Hedonism: “a way of life in which pleasure plays an important role”.

• Contradictory claims have been made about hedonism: some positive and some negative.

The paradox of hedonism

• Pleasure becoming dull over time may lead either to seeking stronger sensations (potentially dangerous) or to disappointment. Hedonism may lead to addiction. Hedonists may become idle, their lives follow no cause or path of self development. Hedonism may erode social bonds, as the hedonist is less sensitive to the needs of others.Positive views on hedonism

Pleasure may reduce stress and so lead to better health. Enjoyment enhances our ability to cope with problems in life and to use more reality control over emotion focused coping.Enjoyment makes us more social and this strengthens social bonds and leads to a better support network.

Hedonic Mind-set and Happiness

• Reflected in personality (Gorman, 1971) – Sensation seekers are happier

• Degree of activities that bring you pleasure

without feeling guilt (Arise, 1996)

– More enjoyment is seen in happier countries

that do not feel guilt

Hedonism and Leisure

• Those who tend to deemed leisure time to be very important in day to day life, are considered to be happier. Especially those who partake in outdoor activities or who participate in sports. Clark and Watson (1988) show that those who are most involved in leisure activities report a better mood on average.

There is currently still controversy as to whether following the rules of Aristotle and eudaimonia or acting according to hedonism will make an individual happy. The Happiness Project proposes a list : half of the items on the list are aimed at satisfying momentarily needs i.e. making yourself feel better at present (indulgence in a film for example) to somewhat console ourselves. The rest are to do with doing things for other people or acting towards achieving more long term goals.

Gretchen Rubin highlights importance of satisfying both short-term and long-term needs and acting in accord of both eudaimonia and hedonism, as opposed to follow one of them and disprove of the other.

Gretchen Rubin Happiness Project

I’m Gretchen Rubin . A few years ago, I had an epiphany on the cross-town bus. I asked myself, “What do I want from life, anyway?” and I thought, “I want to be happy”—but I never spent any time thinking about happiness. “I should do a happiness project!” I realized. And so I have.

. A few years ago, I had an epiphany on the cross-town bus. I asked myself, “What do I want from life, anyway?” and I thought, “I want to be happy”—but I never spent any time thinking about happiness. “I should do a happiness project!” I realized. And so I have.

My happiness project has convinced me that it’s possible to be happier by taking small, concrete steps in your daily life. In my book and on this daily blog, I write about what I’ve learned as I’ve test-driven the wisdom of the ages, the current scientific studies, and the lessons from popular culture. Plutarch, Samuel Johnson, Benjamin Franklin, St. Thérèse, the Dalai Lama, Oprah, Martin Seligman…I cover it all.

If you would like to hear a sample of the audio book based on the Happiness Project, click here:

Doing things for other people or acting towards achieving more long term

We've all had terrible, horrible, very bad days. Here are some strategies I use:

- Resist the urge to 'treat' yourself. Often, the things we choose as 'treats' aren't good for us. The pleasure lasts a minute, but then feelings of guilt deepen the lousiness.

- Try doing something nice for some-one else: 'Do good, feel good'. Be selfless, if only for selfish reasons.

- Distract yourself. Watching a funny movie or TV show is a great way to take a break.

- Tell yourself, "Well, at least I..." Yes, you had a horrible day, but at least you went to the gym, or walked the dog, or read your children a story, or did the recycling.

- Remind yourself of your other identities. If you feel like a loser at work, send out an e-mail to engage with childhood friends. If you think members of the PTA are annoyed with you, don't miss the exercise class where everyone likes you.

- Keep perspective. Ask yourself: "Will this matter in a month? In a year?" I recently came across a note I'd written to myself years ago, that said "TAXES!!!!!!!!" I dimly remember the panic I felt; it's all lost and forgotten.

- Write it down. When something horrible is consuming my mind, I find that if I write up a paragraph or two about the situation, I get immense relief.

- Remind yourself that a lousy day isn't a catastrophic day. Begrateful that you're still on the 'lousy' spectrum. Things could be worse.

Practicing Eudaimonia

Be Social

Positive relations, especially those of higher quality or intimacy, are suggested as being the strongest factor contributing to the benefits of eudaimonaic activity (Deci & Ryan, 2001). Notably, the "helper's high" effect, the release of endorphins in response to altruistic activity, requires direct contact with others (Lucs, 1988). Activities that have direct contact with the benefiting party, meaningful dialogue, and facilitate a sense of understanding are best (Deci & Ryan, 2001). As a result, it is more beneficial to volunteer at a retirement home, interacting with retirees than to donate money.

Be Voluntary and Meaningful

Eudaimonaic activity has more benefit when it is voluntary and motivated by the right reasons. The "helper's high" was only experienced when altruistic activities were voluntary (Lucs, 1988). Furthermore, altruism was only associated with higher well-being when motivated by the concern for the welfare of others rather than anticipation of rewards (Dietz et al, 2007). It is also shown that individuals with the highest well-being are typically those pursuing intrinsic goals for autonomous reasons (Sheldon et al, 2004). It is this effect that researchers suggest may explain why women in an Upstate New York study benefited from volunteering but had a negative relation to paid work and care giving (Moen et al., 1992).

Be Proficient

It is important to feel both competent and confident in performing the eudaimonaic task, as both associated with higher levels of well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Volunteer in an area of your expertise, for example: if you excel at a particular sport, volunteer in a summer camp or after-school program dedicated to that sport.

Don’t Over-do It

Finally, there is a limit to the amount of benefit that can be derived from altruism. Feeling overwhelmed can negate the beneficial effects as seen in a study by Brown et al (2003). Studies show there is a minimum amount of time that must be devoted to volunteer activities to gain benefits but once that amount is met, the volunteer receives no additional benefit. Some studies suggest this threshold is around 100 hours per year, with volunteers showing little benefit under and no additional benefit above (Lum and Lightfoot, 2005).

Benefits and Potential Clinical Applications

Psychological

There are many studies citing the positive affect of eudaimonia, specifically altruism, on well-being and other markers of psychological health (Ryff & Singer, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2001). Altruism, in fact, was associated with higher levels of mental health beyond most other factors (Schwartz, 2003). Altruism has been directly shown to reduce depression, anxiety (Dietz et al, 2007), and stress-related disorders (Lucs, 1988). Altruism was also concluded to be the mechanism responsible for relieving youth of neurotic distress and depression when joining "demanding charismatic groups" (Post, 2005).

Immune System

A significant clinical application lies in altruism’s ability to boost the autoimmune system. A study showed that students watching a film about Mother Teresa's altruistic activities produced a significant increase in the antibody S-IgA compared to those watching a neutral film (Post, 2005). Accordingly, empirical evidence shows that those who volunteer earlier on in life are less likely to suffer from ill health at a later date (Luoh & Herzog, 2002). In similar suit, a 30-year study found that only 36% of women belonging to a volunteer organized experienced major illness compared to 52% of those who didn't belong to such an organization (Post, 2005).

Cardiovascular

Altruism can also protect against and help manage cardiovascular disease through reducing stress and other mechanisms. Adults who volunteered to give massages to infants at a nursery school lowered stress hormones including salivary cortisol and plasma norepinephrine/epinephrine (Post, 2005). Moreover, altruism also induces the secretion of oxytocin, which is associated with positive mood and stress relief (Ryff et al, 2001). The endorphins producing the "helper's high" effect produced a relaxed state that reduced stress (Lucs, 1988). Aside from reducing stress, altruism can also reduce despair and depression, two factors highly related to increased mortality in heart attacks (Dietz et al, 2007). Not surprisingly, states in the US with higher volunteer rates have lower rates of heart disease mortality and incidences (Dietz et al, 2007).

Geriatrics

One of altruism’s most promising applications is towards geriatrics: older volunteers are suggested to receive more benefits from volunteering than younger volunteers. Longitudinal studies have shown volunteers retain greater functional ability than their non-volunteering peers (Dietz et al, 2007). Most significantly, however, is the effect on longevity even when controlling for physical health. In a National Health Interview Survey, volunteers in 1983 were approximately twice as likely to be alive in 1991 as those who hadn't volunteered (Dietz et al, 2007). This effect on longevity has been observed in many studies (Dietz et al, 2007).

Other

Chronic pain can be partially managed through participation in altruistic activities: pain intensity and levels of disability decreased in individuals suffering from chronic pain when they volunteered to help others suffering chronic pain (Arnstein et al. 2002). The "helper's high" induced relaxation has also been documented to relieve pain and improve lupus, multiple sclerosis, voice loss, and headaches. Furthermore, altruism was significantly correlated with long-term survival in individuals living with AIDS. This suggests that the benefits of altruism can be applied to improve the conditions of a wide range of illnesses and diseases.

Criticisms and Limitations

So far, studies have hardly looked at the nature of activities associated with eudaimonia and there is little research directly combining the study of eudaimonia and altruism (Steger, 2008). As a result there is no clear theory available to explain the way in which intrinsic and prosocial motivation interact (Grant, 2008). In addition, the focus of studies looking at altruism is primarily based on evolutionary ideas of altruism.

In light of limited number of studies looking at the interaction of altruistic behaviour and eudaimonia, criticism here will mainly focus on conceptual methodological issues regarding the study of eudaimonic well-being in broader terms.

Conceptual Issues

Kashdan, et al (2008) criticize the lack of consistency regarding definitions of eudaimonia, as well as its conceptual approach. According to their view, eudaimonia is especially difficult to conceptualize as a scientific construct, since it includes a broad number of categories. These in turn represent different sets of ideas including flow, self-determination theory, meaning, and others.

Furthermore, while there are a number of conceptual issues associated with eudaimonia as such, there is also a debate regarding the appropriateness of splitting well-being and happiness into two main dimensions: eudaimonia and hedonism. For instance, Ryan & Deci (2001) note that well-being is more likely to be a multi-dimensional construct, comprising hedonic and eudaimonic aspects at the same time. Therefore, assessing hedonism and eudaimonia separately might not be appropriate in all cases (Biswas-Diener, Kashdan, & King, 2009).

Measures

The study of well-being relies mainly on self-report measures. While newly developed measures such as the Questionnaire for Eudaimonaic Well-being by Waterman et al (2010) have demonstrated high degrees validity and reliabilty, one still has to keep in mind that such measures may be susceptible to biases (Oishi, 2010). When asked to report subjectively experienced well-being from memory, reports might diverge from the actual experience at the time, resulting in a retrospective bias. Individuals might also show self-presentation biases, presenting themselves in a more favourable light and omitting negative information. Also the use of correlational designs can be problematic in that it limits the strength or statistical power of the resulting conclusions. While correlational measures provide insight into links between variables, these measures cannot establish causal relationships.

Additionally, samples used in many studies may have limited representativeness, as they often rely on samples dominated by undergraduate students of similar age and educational status. This sample population does not allow for a generalization to the general population. Representativeness is also limited in terms of cultural context. According to Oishi (2008) there are considerable cultural differences in concepts of well-being as well as factors determining well-being. So far, there has been a strong focus on the study of well-being in a western context. Hence, conclusions which can be drawn from studies mainly apply to western settings.

Another disadvantage of many studies in the field of well-being research is the lack of control conditions. Again, this limits interpretations drawn from the results.

The Question of Causality

The case of altruism and well-being clearly exemplifies the problem of causality. Currently, the question of “what came first; the egg or the hen”, remains unresolved. In other words - does altruism generally increase well-being or is well-being associated with greater altruistic behaviour? There is no agreement regarding the causal relationship between altruism and well-being, yet. For example, a study by Schwartz (2003) links mental well-being and altruistic behaviour, but fails to provide clear evidence regarding the causal relationship of altruism and well-being.

Therefore, helping others might not purely provide meaning, but whether altruistic behaviour leads to well-being and is meaningful may be determined by individuals’ motivation to help (Moreno-Jiménez & Villodres, 2010). Hence, well-being might not be generated by the altruistic act as such, but rather through intrinsic meaning associated with helping others.

"Promising" the "secret" of well-being

There is an industry of self-help books and webpages, promising the “secret for eternal happiness”. While these pages or books often rely on some scientific findings of studies in the area of Positive Psychology, these are often misinterpreted and misapprehended, and most of all presented in a one sided fashion. Headings such as the “The key to happiness revealed” suggest the need for caution.

One needs to keep in mind that the field of positive psychology research, including the study of well-being, is still in its beginnings (Waterman, 2008). Self-help books and mainstream media often oversimplify research findings and ignore conceptual and methodological issues which, in many cases, still limit the clarity of the current state of knowledge.

Examples of biased and simplified reports in the media:

http://www.oprah.com/spirit/5-Things-Every-Happy-Woman-Does/3

http://www.realtruth.org/articles/080602-001-tkthr.html

Key Points:

- While there has been a new wave of interest in altruism and eudaimonia in the context of positive psychology, these concepts have a long history leading back to considerations of ancient Greek philosophers, such as Aristotle.

- Studies such as that of Steger (2008) demonstrate that engagement in eudaimonic activities, including altruistic behaviours, enhances well-being.

- When researching the effects of both eudaimonia and hedonism, it is worth noting that the two are not mutually exclusive

- Eudaimonia is beneficial, mentally and physiologically. In order to receive the most benefit from eudaimonia, choose an activity that is social and meaningful but dont over-do it.

- There are some problems involved in studying links between eudaimonia and altruism. These include ambiguity of concepts such as eudaimonia, methodological issues as well as questions of causality.

References:

Key Readings and Suggested Readings:

Steger, M. (2008). Being good by doing good: Daily eudaimonic activity and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 22-42.

Waterman, A. S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: a eudaimonist’s perspective. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 234-252.

Waterman, A., Schwartz, S., Zamboanga, B., Ravert, R., Williams, M., Bede Agocha, V., Yeong Kim, S., et al. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41-61.

Additional References:

Arnstein, P., Vidal, M., Well-Federman, C., Morgan, B., and Caudill M. (2002) “From Chronic Pain Patient to Peer: Benefits and Risks of Volunteering. Pain Management Nurses, 3(3): 94-103

Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T. B., & King, L. a. (2009). Two traditions of happiness research, not two distinct types of happiness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(3), 208-211.

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing Support may be More Beneficial than Receiving It: Results from a Prospective Study of Mortality. Psychological Science, 14, 320-327.

Carter, A. (2005). Evolution and the Problem of Altruism. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, 123 (3), 213-230.

Demir, M.,& Sun, Z. (2004). Self-concordance and subjective well-being in four cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(2), 209-223

Dietz, N., Grimm, R., & Spirng, K. (2007). "The Health Benefits of Volunteering: A Review of Recent Research." Office of Research and Policy Development, Corporation for National and Community Service. Washington, DC.

Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. The Journal of applied psychology, 93(1), 48-58.

Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: the costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 219-233.

Lucs, A. (1988). Helper’s high: volunteering makes people feel good, physically and emotionally. Psychology Today, (Oct).

Lum, T.Y. and Lightfoot, E. (2005) “The Effects of Volunteering on the Physical and Mental Health of Older People.” Research on Aging, 27(1): 31-55.

Luoh, M-C. and Herzog, A.R. (2002) “Individual Consequences of Volunteer and Paid Work in Old Age: Health and Mortality.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(4): 490-509.

Moen, P., Dempster-McClain, D. & Williams, R.M., (1992) “Successful Aging: A Life Course Perspective on Women’s Multiple Roles and Health.” American Journal of Sociology.

Moreno-Jiménez, M. P., & Villodres, M. C. H. (2010). Prediction of Burnout in Volunteers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(7), 1798-1818.

Myers, D. G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55, 56–67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (2000). Interpersonal flourishing: A positive health agenda for the new millennium.

Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 30–44.

Ryff, C.D. & Singer, B. (1998). The Contours of Positive Human Health. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), pp. 1-28.

Oishi (2010). Culture and Well-Being: Conceptual and Methodological Issues.

In (Eds) Diener, E, Helliwell, J.F., Kahneman D., International differences in well-being. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Post, S. G. (2005) "Altruism, Happiness, and Health: It’s Good to Be Good". International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12(2), 66–77.

Schwartz, C. (2003). Altruistic Social Interest Behaviors Are Associated With Better Mental Health. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(5), 778-785.

Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Ryan, R. M., Chirkov, V. I., Kim, Y., Wu, C., Taylor, B., & Barling, J. (2004). Identifying sources and effects of carer fatigue and burnout for mental health nurses : a qualitative approach. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 13, 117-125.

Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678-691.

Moodle Docs for this page

Moodle Docs for this page