Wiki

Flow- the psychology of optimal experience

In 1975 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defined ‘flow’ as the ‘holistic sensation that people feel when they act with total involvement’. In 2002, Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi extended this definition to the experience of working at full capacity, with intense engagement and effortless action, where personal skills match required challenges. The word flow is used to define this state as it is the word most people that Csikszentmihalyi studied used in their descriptions of how it felt to be on top form eg. 'I was carried on by the flow'

9 factors which accompany the experience of flow were identified (Csikszentmihalyi 1990);

-clear goals

-concentration

-a loss of self-consciousness

-loss of sense of time

-feedback

-balance between ability and challenge level

-sense of control

-intrinsic rewards

-becoming one with the activity

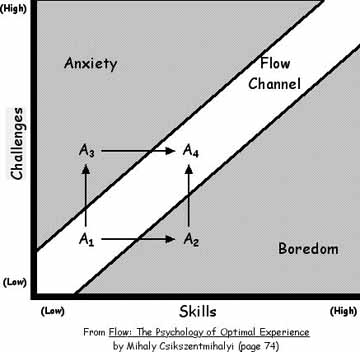

One of the main necessities to achieve a state of flow is for the perceived level of skills to match the perceived level of challenge (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

This graph shows the relationship between skills and challenges. In his book, Csikszentmihalyi uses the example of a boy named Alex, who plays tennis to explain this graph. Ponit A represents Alex at different points of time. At point A1, Alex is in flow as his perceived skill level is in balance with the difficulty of the perceived task. At this stage, as a beginner tennis player, the challenge Alex faces may be hitting the ball over the net. When his skills improve, he will grow bored of hitting the ball over the net as his skills will be higher than the challenge (A2). However, if Alex is faced with a highly skilled tennis player the thought of playing a game with them will lead Alex to be anxious (A3) as his perceived skill level will be lower than the perceived challenge level. Alex can get back into flow by undertaking a task that is in balance with his slightly improved skills (A4).

For a brief visual introduction to flow, click the photo below:

A History of flow

Meditation

Wild claims

Applications of the flow theory

Flow: put into practise

Criticisms

Connections to other areas

Future directions

Key points

References

Flow was first described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1975) as the experience one achieves when they become wholly involved in an activity. During Flow, actions seem to occur naturally and follow on from one another without requiring any conscious intervention (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975).

However, prior to this description, what is now defined as 'flow' had been described in previous research by Murphy (1972) and Unsworth (1969) among others. Although in these instances the experience was not termed 'flow', Murphy and Unsworth had attempted to describe optimal experiences in specific activities. For example, Murphy was concerned with the experience in golf and Unsworth was concerned with the experience in rock climbing. Therefore, such theories had generally described flow in accordance with the activity being discussed. Cskiszentmihalyi was first to describe flow as an independent process which could be achieved in a variety of activities. He argued that Flow would not always occur in specific situations, nor was it limited to specific situations or activities.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's description of flow shares many of the characteristics of what Maslow calls 'peak experiences' (1962, 1965, 1971) and what de Charms (1968) terms the 'origin' state . The 'origin state' was described by Koch as the "domination of the person by the problem context" (Koch, 1956 p67-68). In this state, "you do not merely 'work at' or 'on' the task: you have commited yourself to the task and in some sense you are the task." (Koch, 1956 p67-68). The paralells with flow are easy to see.

As a result of the overlap between the experiences, Privette (1983) conducted a review of peak experience, peak performance and flow. Privette described all three of these phenomena as positive subjective experiences. They are all inter-related and yet each has its own characteristics which mean it can also occur in isolation (Privette, 1983).

A brief description of each would be:

Peak Experience: Moments of great happiness and enjoyment (Maslow, 1962). An experience of intense joy.

Peak Performance: Episode of superior human functioning: making the highest use of human potential and human power (Privette, 1983).

Flow: Enjoyable and rewarding experience which occurs when one becomes completely immersed within an activity (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975).

The three are clearly inter-related and it is easy to see how aspects of peak performance and experience are involved in Flow.

Meditation, a flow experience in culture

Although identified by Csikszentmihalyi in the early 1975 flow like states have been described and sought after for many years through various types of meditation.

For flow, according to Csikszentmihalyi, one’s skills need to be matched to the task difficulty (1990). Meditation can elicit flow becuase it is not simply a deep state of relaxation, but rather an act that requires practice and skill. Wetering (1972) explains his personal struggles when he first started meditating while living in a Japanese zen monastery. He describes how difficult it is to keep your mind focused on one object or idea, called a koan, and how difficult it is to sit perfectly still for more than 20 minutes at a time. Over time people are able to master this task and sit perfeclty still, focused on the koan. it is only when the meditator's skill level is high enough that people are able to become fully emersed in meditation.

Intense focus descibes both a person in a state of flow, and a person in meditation. During some types of meditation, the person focuses on a subject called the koan. The koan is focused on until “everything drops or breaks away and nothing is left but the koan which fills the universe” (Wetering, 1972, p.15). There is a differnce between the focus experienced in flow and during meditation. during flow, the person is focused on the task they are doing; during meditation, the person is focusing on an object that might have nothing in common with meditation, for example a rock, or love.

Meditation differs from flow experiences in that flow has elements of ecstasy and timelessness (Csiksezentmihalyi, 1990). In meditation, however, the focus is to bring concentration inward so that the person meditating stops sense perceptions and “stands within himself” (Gombrich, 1988), and regulation of attention is from moment to moment (Reavley & Pallant, 2009). Mediation is unlike flow in the experience of time because people in flow do not notice tie passing, but during meditation there is a focus on experiencing time passing

Unlike flow, people meditate for different reasons. In flow, the act itself is the source of motivation, but for some meditation is done because it is part of the eightfold path (The Big View, n.d.). Others meditate because meditation might be beneficial for health (BBC, 2003). These extrinsic motivations are differnt than the intrinsic motivation within the flow experience.

A link for a

.The extent to which flow experiences can impact on one’s life have been greatly exaggerated. Morris (2003) claimed that flow is a “creative and accessible alternative for reaching sound mental health", however, no empirical evidence exists to support this statement.

Some describe flow as the “ultimate in harnessing emotions” in which emotions are “energized and aligned with the task at hand” (Wikipedia, 2009). However Csikszentmihayli's description of flow does not inlcude emotions during the flow experience.

Claims about the effects of flow in the work place have also been exaggerated. Chiu (2006) claimed that giving employees tasks that match thier skill level, the employer will prevent procrastination. Csikszentmihayli (1990) outlined the conditions requried for flow to happen, but he did not claim that if these conditions were present flow will happen.

Applications of the Flow Theory

Csikszentmihalyi’s flow theory can be applied to six main fields: music, religion, education, sport, occupation and clinical.

Music

The state of flow, whereby one is completely absorbed in a current activity, is a state that countless improvisational musicians aim for: “peak experiences or flow states assist improvisers, to move not only beyond the literal texts of referents but also beyond their own cognitive limits in non-flow states” (Parncutt & McPherson?, 2002, pp. 119).

Due to this, being in a flow-like state is highly beneficial to a musician developing their creative art and this provides a significant motivator to continue to learn the behaviours and skills that improvisation requires (Parncutt & McPherson?, 2002).

Religion

For centuries, Eastern religions have practised by ideas which are very similar to Csikszentmihalyi’s description of changes in self-concept during flow. For example, Buddhists practise the art of fusing the ‘self’ and the ‘object’; denying existence of the self as a separate phenomenon. This leads to clinical applications: “Buddhism attempts a radical resolution to all psychological illnesses by ending their source, the self…” (Muzika, E.G., 1990, pp.59).

Education

Csikszentmihalyi states that learning opens the mind, enabling it to envision the overall goal of the current task. According to the flow theory, an optimal state will only occur when the skill level matches the challenge level (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Therefore, an optimal experience during learning will only occur when the educational task sufficiently tests the student.

The application of flow to education has led to research on methods of teaching, such as the Montessori Method , that encourage flow (Wikipedia, 2009). Rathunde and Csikszentmihalyi (2005) conducted a comparison study of Montessori and traditional educational methods. The 290 student sample was matched demographically. Motivation and experience quality were measured using the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) and questionnaires. Montessori students described higher levels of energy, intrinsic motivation, flow and concentration in comparison to other students. This provides evidence that being in the state of flow benefits learning experience.

Sport

Researchers into the field of sports psychology have found the relationship between flow and physical performance to be changeable. Therefore, research continues to be focused upon how the experience of flow affects performance (Schuler & Brunner, 2009).

Due to the multiple characteristics that can define an experience as optimal (complete mental absorption, distorted sense of time etc.), athletic performance may be affected by several factors. Some characteristics may have a direct effect: high levels of concentration and feelings of control are said to promote performance. Furthermore, because the experience of flow is an enjoyable one, we are more liable to repeat physical performances that create it, leading to increased levels of motivation (Shuler & Brunner, 2009).

Csikzentmihalyi’s theory suggests that flow should lead to enhanced performance. For example, a beginner marathon runner may accomplish flow by completing a race. However, once the runner has trained and bettered their performance, skill level will be higher than challenge level and the runner may experience boredom. In order to achieve optimal experience again, the runner may have to complete the marathon in a shorter time, hence, increasing the challenge level to match their skill (Rogatko, 2009).

However, Schuler and Brunner (2009) studied three marathon runners and measured their flow experiences four times during a race. The results showed that although flow experience during a race was associated with future motivation, it did not relate to performance. Performance was determined by training behaviours.

Occupation

Csikszentmihalyi (1990) stated that when flow is experienced during work and in work based interactions, an individual can greatly enrich their life. Therefore, positive psychologists have investigated the concept of flow in the workplace in relation to supporting wellbeing and inhibiting stress related illness, arguing that flow will counteract stress (Howard, 2008). Several interventions for this, inspired by positive psychology, have been proposed by Howard (2008).

Cultural and individual differences exist in a person’s ability to find flow in work. Individuals with autotelic personalities have the ability to create flow regardless how rich the working environment is (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Clinical

Several studies have reported that flow relates to higher positive affect. One such study by Rogatko (2009) induced high and low levels of flow in two groups of undergraduates. Each group partook in a flow activity for one hour. Rogatko used the Flow State Scale-2 to measure effects; the most valid tool to measure flow. Results showed the high flow group to have increased levels of positive affect. This study provides evidence that inducing flow in the population would lead to positive clinical outcomes.

War

To date only one article about the implications of flow in war have been published, but the area requires further enquiry. Harari (2008) notes that flow is commonly experienced during war by soldiers, and he believes that flow can increase soldiers efficiency and well-being. Harari also states that soldiers should be taught how to enter flow to improve their well-being and efficiency during war. Implications for this are widespread. currently more evidence is needed, but if Harari's hypothesis is correct, then people who work as emergency response personnel, doctors and police should be taught this in order to improve their ability to respond quickly and accurately to a disaster, and to improve their well-being following the event.

It is evident that flow can be experiened in both work and leisure, Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre? (1989) actually found that optimal experiences occur three times more frequently in work than in leisure, despite leisure being a time when people are able to choose which recreational activities they pursue.

Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre? (1989) found the work tasks which produce the highest rate of flow are;

- talking about problems,

- typing

- and assembly work.

These are all tasks which require a certain level of challenge and skill to create the balance which Csiksentmihalyi claims is essential for achieving flow. Delle Fave & Massimini (2005) also found that work activities induced flow-like experiences. On examining students, they found studying creates flow for many students due to their commitment to learn which sets high challenges, therefore allowing students to develop skills in order to overcome them, hence creating flow.

Leisure activities appear to produce lesser amounts of flow. Csikszentmihalyi & Lefevre (1989) found the activity which produced the most optimal experience was driving. This is ironically a task which some would argue is not an enjoyable, leisurely activity. Also, the act of talking to peers and family produced flow, a task which adolescents claim to gain the most enjoyment from (Csikszentmihalyi et al., 1977). The leisure task which appears to be the most common in Csikszentmihalyi's study was watching television. This act however contributed the most to non-flow experiences and is absent of relevant challenges and skill required (Delle Fave & Massimini, 2005). This rasies the question to Csikszentmihalyi's theory of psychological selection which claims that individuals try to escape activities resulting in negative mood states and seek out activities which will induce flow (Delle Fave & Bassi., 2000).

Hunter & Csikszentmihalyi (2000) acknowledge sport as an ideal example of experiencing flow. They identify the "in the zone" feeling athletes get as being a prime example of flow (Hunter & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000:15). Sport provides a degree of challenge which an athlete's skill has to meet, it provides definitive goals and can consume the athletes concentration during the time the sport is being played. Professional athletes claim to be able to recount their exact actions with a feeling of exhilaration and becoming one with their task after being in a state of flow (Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1999).

Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre? acknowledge a possible cultural divide and show that Thai cultures spend their leisure time doing ativities other than watching television such as playing musical instruments, carving and weaving, all of which are more likely to produce flow as they presen a challenge and require skill.

It is clear from research that people have reported experiencing flow after performing certain activities. However, there is no evidence of an exercise which one is recommended to perform which will guarantee an optimal experience.

- Western bias: One of the components of flow is that it has clear goals. Therefore, some researchers thought that it was a very western psychic phenomenon (Sun, 1987). Flow is thought to be too active and goal directed to be a panhuman trait, however, even though the context of flow differs between cultures the overall dynamic of flow remains universal ( Csikszentmihalyi, 1988).

- Assuming too much: Csikszentmihalyi(1990) defines the world as a place of chaos in which people provide order to the chaotic information that they perceive. However, this theory may be assuming too much as it seems to ignore those who feel controlled by the external environment and do not perceive the necessary control to provide order to this chaos.

- No mention of how to achieve flow: In his book- Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Csikszentmihalyi mentions the benefits and dynamics of flow. Although he claims that flow should be experienced more often, there is no mention of how flow can be achieved.

- Flow requires full concentration: One of the nine characteristics of flow is full concentraion to the task at hand (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). However, if flow requires full concentration, after experiencing a state of flow one would expected to be tired. However, evidence shows the opposite. Students who did not report frequent flow experiences and those who did were studied (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Subjects were asked to pay attention to flashing stimuli and their corticle responses were measured. Those who reported flow frequently had decreased activation when concentrating, whereas, those who experienced flow rarely their activation went up significantly (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). This aspect of whether concentration causes tiredness or not deserves more attention.

- The claim that one can find flow almost anywhere: Csikszentmihalyi claims that flow can be found in almost any activity even working at a cash register or ironing clothes (Csikszentmihalyi, 2009). However, it was found that the quality of experience during a junior writing task was associated with the teachers rating of the theme (Larson, 1988). Furthermore, a significant relationship was found between interest in the task and flow experiences (Ainley et al, 2008). Therefore, it is questionable whether or not flow can be experienced throughout every activity or if interest in the task is necessary.

- Limited evidence for flow in neuro-imaging studies.

- The individual seeks to replicate flow experiences: As the flow state is intrinsically rewarding (Csikszentmihalyi, 2002) and is likely to enhance the overall quality of the experience, mental health, objective performance, talent and creativity (Moneta & Csikszentmihalyi, 1996) one is likely to want to repeat the experience. However, it is found that people are 3 times more likely to watch TV than engage in an active task which may result in flow (Nakamura&Csikszentmihalyi, 2002). If one is intrinsically motivated to return to activities from which they have experienced flow then they will be expected to carry out these activities more frequently than passive activities such as watching TV.

- Methods used to measure flow: Both the interview and questionnaire techniques are thought to be limited (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002). Firstly they rely on retrospective reconstructions of past experiences. As the study of flow relies heavily on subjective experience it is important to capture the full effects of the experience, which memories may fail to do. Secondly, when asking for the frequency or intensity of a flow experience subjects must average across many discrete experiences to compose a picture of the typical experience then make an estimation, which may be affected by different moods. Moreover, the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) also has flaws. In 500 ESM self-reports respondents indicated that 49% of the experiences captured them doing something different to what they were thinking about (Voelkl & Ellis, 1998). This is problematic as there may be a discrepancy between what they were doing and what they were thinking. An example to this may be a business man on his coffee break who is drinking coffee but thinking about an important business merger. This participant may report that they are experiencing a low level activity which requires low skill (drinking coffee) as opposed to reporting that they are experiencing a high level of skill and challenge (their thought process). This may also yield a problem when studying the difference between work and leisure.

-The ambiguity of flow: Csikszentmihalyi asserts that the experience of flow is best described as the “optimum experience one can achieve from the task at hand”(Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). However, in his study of American highschoolers the highest feelings of happiness, sense of control and clarity where reported when the task challenge level was markedly lower than their skill level (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). As all of these components fit in with the 9 components of flow, and can be described as 'optimal' then this contradicts Csikszentmihalyi's view that challenges and skills must be equal in order to achieve flow.

Similarities can be drawn between theories of intrinsic motivation and the flow theory. Abraham Maslow produced a hierarchy of needs in order to explain motivation. The top of the hierarchy is a desire for self-actualization which was described as “a need to discover one’s potentialities and limitations through intense activity and experience” (Csikszentmihalyi 1988, p. 5). Acknowledging intrinsic motivation can be seen as the starting point of the flow theory.

Berlyne(1960,1970) identified the correlation between complexity and pleasantness of stimuli, further, he identified that hedonic tone is a function of the complexity of the stimuli(the more complex, the more pleasent). It was assumed that individual would be intrinsically motivated to seek tasks that were not too simple nor too difficult (Berlyne, 1960; Berlyne, 1970). As Csikszentmihalyi also focuses on the complexity of tasks and levels of skills, similarities can be drawn from these theories. However, the main difference between the two theories is that Berlyne’s theory depends on objective definitions of task complexity, whereas the flow theory relies on subjectivity.

Recent contributions and focus of future research

The inherent benefits of flow (focused and efficient production and increased satisfaction towards the task at hand) make it particularly relevant to an applied setting and subsequently a large proportion of the flow research since Csikszentmihalyi first proposed his model is devoted to the occurrences of flow within education, therapy and the workplace (see above). Recent research suggests that flow not only improves performance on a task but increases the individual’s overall sense of well-being and self-esteem, even long after the task has been completed (Emerson, 1998). Moreover in studies in which flow is prevented, or the individual reports not reaching a flow state, disengagement follows and continual flow deprivation has been linked to burnout in some cases (recently, Neualt 2005). Thus this focus in the literature appears to be merited and reflects the importance of investigating how flow can be developed in everyday life.

Individual differences in Flow experiences

In order to usefully facilitate flow in these settings it is first necessary to answer how flow is achieved. Csikszentmihalyi (1992) asserts that flow is a universal human experience, “a staple of life… not a luxury processed by only some individuals" (p 364). Yet he concedes that there are differences in the quantity and intensity of flow experiences between different people. Some of these discrepancies can be accounted for by differences in the tasks that 'produce' flow experiences, as well as the different criteria and measurement techniques used within the literature. But even in roughly comparable situations it appears that some individuals more readily enter flow states than others. This might suggest that it is not the task that is primarily responsible for producing or preventing flow but our attitude towards it. For example, why is it some people report a sense of flow from extremely challenging and sometimes even adverse situations (p370), whilst others of similar skill base shrink back from the task? If this is so could it be that these differences arise out of steadfast susceptibilities to one attitude or the other; or can individuals 'train' themselves to reach a flow state? Though there is currently no research into the personality correlates of flow susceptibility, recent studies into meditation suggest individuals can become better at flow (see Meditation section for a full explanation into how meditation is linked to a flow state).

Neural correlates of flow?

Brefezynski-Lewis et al. (2007) used fMRI to measure the brain activity of people who had been regularly meditating for more than 20 years as they completed complex cognitive tasks. They found that regions typically associated with sustained attention actually showed decreased activity from baseline. This suggests that these individuals are either more efficient in their recruitment of brain regions to allow concentration, or that they require less energy to reach sufficient levels of concentration for the task. When the same experiment was repeated on novice meditators ( less than 2 years), it was revealed that activity was higher in these regions during task, but still markedly less than for non-meditating subjects. This suggests that the brain has some plastic capacity for concentration that can be manipulated with cognitive strategies such as meditation. Given what we now know about brain plasticity, this does not seem like an unlikely assumption (see Ge et al, (2007) for a review on recent plasticity literature; see Dweck (2006) for her theory on changing mindsets and approaches to tasks).

Group flow

There is also some evidence that flow needn’t necessarily be an individual experience. Sawyer (2007) found evidence of groups entering a state of flow where they described themselves as entering a state of “heightened synchronicity…and receptiveness”(pg 64) to one another when working together on the same task. Sawyer describes the following as being necessary prerequisites for group flow:

- Comparable skills among team members

- Team members all contribute and share knowledge

- Highly standardised task reduces likeliness of flow state

- If group members are too familiar with each other, challenge and concentration is reduced, reducing likeliness of flow

Despite proliferating empirical examples of flow in practise, the literature is still largely held back by semantic debates of what constitutes flow and the consequently divergent measurement criteria and methods. In order to really develop the theory, consensus over these matters has to be resolved in future research.

Flow was developed by Csikszentmihalyi to explain the situations during which we are most happy. - It involves being wholly involved in an activity so actions flow naturally one after the another.

- Skill levels have to match the challenge at hand.

- Research into applications of the flow theory show that being in the state of flow has benefits for many areas including health, sport, work and education.

- Current research is focused on how one achieves Flow, if there are neural correlates of Flow and whether or not Flow can be achieved in groups.

- Flow is achieved in a work environment more often than leisure. This can be due to more challenging activities being offered in the workplace, and people are not utilising their leisure time in an appropriate way to achieve flow.

- There are various criticisms of flow mainly due to the fact that it is a vague and subjective concept, which is hard to measure.

Starter Reference

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper.

Essential Reading

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Play and Intrinsic Rewards. Journal of Humanistic psychology, 15(3), 41-63.

- Moneta, G.B, Csikszentmihalyi, M (1996), "The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience", Journal of Personality, Vol. 64 No.2, pp.275-310

- Dietrich, A., (2004). Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the experienec of flow. Consciousness and Cognition. 13 p. 746-761 Retrived from: science direct

Ainley, M., Enger L., & Kennedy, G. (2008) The elusive experience of ‘flow’ : Qualitative and quantative indicators, International Journal of Education, 47, 109-121

BBC (2003). Meditation ‘good for the brain.’ Retrived from: BBC 11/09

Berlyne, D.E. (1960) Conflict, arousal, and curiostiy. New York: McGraw?? -Hill

Berlyne, D.E. (1970) Novelty, complexity, and hedonic value. Perception and Psycophysics, 8, 279-286

Brown, D. (2009). Mastery of the mind: East and west excellence in being and doing everday happiness. Annuals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 1172 , 231-251.

Chiu, K., (2006). Solving procrastination: An application of flow. Vitural Worlds. Retrieved from: Kevinchui.org

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper.

Csikszentmihalyi, I. and Csikszentmihalyi M. (1988). Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Play and Intrinsic Rewards. Journal of Humanistic psychology, 15(3), 41-63.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. and LeFevre?? , J. (1989) Optimal Experience in Work and Leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), 815-822.

- De Chams, R., (1968) Personal Causation. New York: Academic Press.

- Delle Fave, A. and Massimini, F. (2005) The Investigation of Optimal Experience and Apathy, European Psychologist, 10(4), 264-274.

Duckworth, A. L., Steen, T. A. & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practise. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629-651.

Howard, F. (2008). Managing stress or enhancing wellbeing? Positive psychology's contributions to clinical supervision. Australian Psychologist, 43 (2), 105-113.

Harari, Y., (2008).

Combat flow: Military, political, and ethical dimensions of subjective well-ebing in war.

Review of General Psychology. 12. pp. 253-264

Hunter, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). The 'Phenomenology of Body-Mind: The Contrasting Cases of Flow and Sports and Contemplation. Anthropology of Consciousness, 11(3-4), 15

- Kelley, T. M. (2004). Positive Psychology and Adolescent Mental Health: False Promise or Tru Breakthrough? Adolescence, 39 (154), 257-278.

- Koch, S. (1956) Behaviour as "intrinsically" regulated: Work notes toward a pre-theory of phenomena called "motivational". In M. R Jones (Ed.). Nebraska Symposium on motivation. Lincoln: University of Nevada Press, 1956.

Larson, R. (1988) Flow and writing. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & I.S. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds), Optimal expreince: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness (pp.150-171). New York: Cambridge University Press

Maslow, A. (1962) Toward a Psychology of Being. Princeton, New Jersey: Van Nostrand.

Maslow, A. (1965) Humanistic Science and Transcedent Experiences. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 5 (2), 219-227.

Maslow, A. (1971) The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York: Viking.

Murphy, M. (1972) Golf and the Kingdom. New York: Viking

Muzuka, E. (1990). Object relations theory, Buddhism, and the self: Synthesis of Eastern andWestern approaches. International Philosophical Quarterly, 30 (1), 59–74.

Moneta, G.B, Csikszentmihalyi, M (1996), "The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience", Journal of Personality, Vol. 64 No.2, pp.275-310

Morris, J., (2003). Life issues. MentalHelp?.net. Retrieved from: mentalhelp.net 16 November 2009

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C.R. Snyder & J. Lopes (Eds), Handbook of Positive Psychology (chapter 7).New York: Oxford University Press

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). The concept of flow. In C.R. Snyder & J. Lopes (Eds), Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (chapter 18).New York: Oxford University Press

Parncutt, R. & McPherson?, G. (2002). The science and psychology of music performance: Creative strategies for teaching and learning. Oxford University Press: US.

Partington, S., Partingtin, E. & Oliver, S. (2009). The dark side of flow: A qualitative study of dependence in big wave surfing. Sports Psychologist, 23 (2), 170-185.

Privette, G. (1983). Peak Experience, Peak Performance, and Flow: A Comarative Analysis of Positive Human Experiences. Journal of Persnality and Social Psychology, 45 (6), 1361-1368.

Rathunde, K & Cszentmihalyi, M. (2005). Middle School Students’ Motivation and Quality of Experience: A Comparison of Montessori and Traditional School Environments. American Journal of Education, 111 (3), 341-371.

Reavely, n., Pallant, J. (2009). Development of a scale to assess the meditation experience. Personality and Individual Differnces. 47 p. 547-552. Retrived from: science direct

Reberio, K. L. & Polgar, J. M. (1999). Enabling occupational performance: Optimal experiences in therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65 (1), 14-22.

Rogatko, T. P. (2009). The influence of flow on positive affect in college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10 (2), 133-148.

Schüler, J & Brunner, S. (2009). The rewarding effect of flow experience on performance in a marathon race. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10, 168-174.

Steele, J. P. & Fullagar, C. J. (2009). Facilitators and Outcomes of Student Engagement in a College Setting. The Journal of Psychology, 143 (1), 5-27.

Sun, W. (1987). Flow and Yu: comparison of Csikszentmihalyi’s theory and Chuang-tzu’s philosophy . Paper presented at the meetings of the Anthropological Association for the Study of Play. Montreal, March.

The Big View. (n.d.). The noble eightfold path. Retrived from: The Big View site

Unsworth, W. (1969). North Face. London: Hutchinson.

Voelkl, J., & Ellis, G. (1998). Measuring flow experiences in daily life: An examination of the items used to measure challenge and skill. Journal of Leisure Research, 30(3), 380–389.

Wetering, J., (1972). The empty mirror: Experiences in a japanese zen monastery. Routledge and Kegan Ltd: London

Wikipedia. (2009). Flow (psychology). Retrieved from: Flow wikipedia 17 November 2009.

Wikipedia. (2009). Flow (Psychology). Retrieved from: Flow wikipedia. 25.11.09

- //

Moodle Docs for this page

Moodle Docs for this page