Peer Interaction - When is peer interaction effective?

Introduction

Key Paper

The Importance of Talking in Class

Peer Assessment

- Mixed Results

- When is Peer Assessment Useful?

- Reciprocity Effects

- Thinking Style

- Optimum Conditions

Peer Interaction in Online Settings

- Key Paper with Summary

- Peer Interaction in Other Online Platforms

Applications of Peer Interaction

Conclusion

References

Introduction

Peer interaction is increasingly incorporated into learning environments. It is therefore necessary to establish the effectiveness that peer interaction has on learning, as well understanding its limitations. Aspects of peer interaction has been found to facilitate reasoning and thinking, which heightens a student's understanding of a topic, resulting in learning improvements. Peer interaction is a vast concept. Several aspects of peer interaction will be addressed including inclass discussion, peer assessment and virtual learning environments.

Key Paper: Peer Instruction: Ten years of experience and results.(Crouch and Mazur, 2001).

Crouch and Mazur made a major contribution to research on peer interaction through the striking benefits that such interaction had on students performance. Ten years worth of data were analysed in this study, hence this paper provides a wealth of evidence that peer interaction has positive effects on students learning.

Students were asked challenging problem based questions within class and were instructed to discuss their believed correct answer with other classmates. This method provoked debate within the student groups, encouraging students to generate explanations for their own perspective whilst exposing students to alternative viewpoints. Students were able to reconsider their own ideas in light of this and build a deeper understanding of the concepts.

Dramatic improvements were evident when peer interaction students completed tests to gage their knowledge and understanding (The Force Concept Inventory and Mechanics Baseline Test), when compared to the scores of students who were to traditional, non interactive learning. In fact, students performance was enhanced by almost threefold. Additionally, peer interaction considerably increased scores of problem solving ability, thus indicating that peer interaction promotes a deeper and more valuable learning experience.

The Importance of Talking in Class.

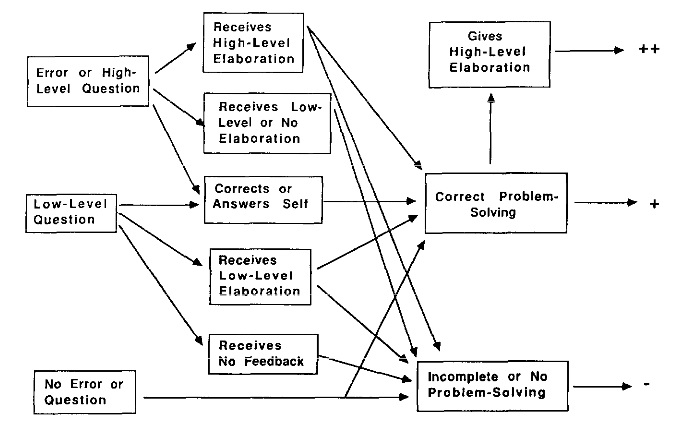

Webb (1989) proposed a model of learning by peer interaction, in which she claimed effectiveness of the interaction on learning was directly related to the student experience of the interaction, and that this depended on how students behaved during the encounters. She reviewed previous evidence linking student experience with the effectiveness of peer interaction and attempted to explain the differences between individuals. The figure below is reproduced from the paper and shows the behaviours discussed.

Being able to solve the problem, then, depends both on an individual’s initial ability and the interactions which then occur. Somebody who understands the material well to start with may have little involvement in the discussion, asking no questions, and may still be able to solve the problem and give elaborate explanations. If someone was incapable of understanding the material initially, asking no questions and giving no input which can then be corrected gives a poor outcome. Differences between high- and low-level elaborations are also pointed out. Low-level elaboration is simply providing an answer to a question without explanation. High level elaboration is more effective than this, given that the individual in receipt of the explanation can understand it.

Giving explanations has also been correlated with greater success. This is thought to be due to the need for understanding the material in order to give explanations, but also that explaining a concept to individuals whose grasp of it is poor forces the individual giving the explanation to manipulate the information more, for example by changing some key terms into more simple language.

Webb claimed that the differences in behaviour in group interactions as described above (ie. whether somebody will offer elaborate explanations or simply answer the question, and whether someone will ask questions) depends on individual differences, reward structure, group structure and task structure as described below.

Individual Differences

Webb claims that the personality of an individual determines their behaviour in the context of peer interactions. An introvert, for example, may gain less from peer interaction due to the decreased likelihood that they will ask questions when they need to, although it was pointed out that interactions are not useless in these cases as they may benefit through simply listening to the discussion carried out by their peers. Webb also proposed that introversion may be associated with a decreased likelihood of producing elaborate explanations during the discussion although empirical evidence for this is scant, with four studies highlighted in the paper in which introversion and decreased high-elaborations have been shown not to be correlated.

Reward Structure

The preference for working alone is explained by the possible perception of a reward structure which is individualistic or competitive, such as tests which are marked on the curve (this is where grades are given depending on how students have scored relative to one another, so there is no percentage cut-off for each grade band and the number of students who will get each grade can be known in advance – so the ten best students will get an A, for example). In this case, helping peers may not be perceived as advantageous, so students may be keeping their cards close to their chests, so to speak.

Group Structure

The make-up of a group based on how capable the individuals are has been connected with the effectiveness of peer interaction. Groups which include individuals of a similar level of ability produce more elaborative explanations, enhancing the effectiveness of the interactions. Group composition based on gender has also been shown to have an effect on the types of interaction occurring. Groups with an equal gender ratio were outperformed in terms of giving explanations by imbalanced groups, both where males were in the majority and where females in the majority.

Task Structure

Tasks which actively encourage students to give more explanations, such as those which involve a “Jigsaw” structure produce more high-level elaboration. This is where a task is divided and each section given to a different student to explain to the others. Role play in which students are assigned as “experts” has the same effect, as students have to explain information which only they have been given to other members of the group.

Webb’s paper could suggest that peer interaction may only be effective where at least some members of the group have already grasped the material. However, Smith et al. (2009) contest this, claiming that correct answers increase after group discussion, even when none of the students originally knew the correct answer. This suggests that something about the group discussion itself has an impact on educational results. This is in contrast to the claims made by Howe, McWilliam and Cross (2005) who state that the delayed effects of peer interaction (such as those found by Howe, Tolmie and Rodgers (1992), where students had no greater understanding on immediate testing after discussion, but did four weeks later) are a result of further individual study which is carried out due to the confusion caused during peer interaction. Either way, peer interaction is having a positive effect on learning and so seems only to be a good thing!

The study by Howe et al. (1992) looked at primary school aged children. It could be, then, that the results of their study may have been different were the participants college/university students as in many of the other studies in this area. Perhaps, peer interaction is only effective amongst individuals of a certain age. This does not seem to be the case though, as Azmitia (1988) found that collaboration effectively enhanced learning outcomes for lego building in five-year-olds, without the possibility of individual practise as a mediating factor. It could be that the effects of peer interaction on learning and whether this is mediated by extra practise taken on due to confusion caused by the interaction, depends on the task at hand rather than the age of participants.

King (1990) added to the idea that task structure is important in creating effective peer interactions. They compared students in a discussion group, with students using guided and unguided reciprocal peer questioning. Guided questioning involved participants individually studying questions posed to them by teaching staff, before using these to generate their own task-specific questions which they then posed to their peers, whereas unguided involved participants thinking of questions in advance but with no original questions to base these on. The guided group asked more questions which involved critical thinking, provided more elaborative explanations and outperformed their unguided and discussion group counterparts on testing. However, it has been suggested that this kind of scripting and directing of discussion may become problematic if overused. Dillenbourg (2002) discussed this in relation to online learning communities in which scripts are often used to enhance collaboration, with scripts being defined as a set of phases which the students involved must go through in order to complete their group work. He postulates that scripts may disturb natural discussion and natural problem solving which would have gone on otherwise. He also points out that scripts which require certain questions to be asked risk the formation of discussions which are somewhat similar to teacher-student interactions, in which the student believes that the teacher already understands that which is being asked. The motivation behind providing an explanation, then, is different, and so the answers given may also differ accordingly. For more information on peer interaction in online contexts see here.

To sum, peer interaction generally has been found to have a positive effect on learning although the results differ according to the type and quality of interactions between individuals. It has been suggested that peer interaction can even be effective where nobody involved in the discussion was able to correctly answer questions on the material beforehand, and in very young children thought to be at an egocentric stage of development.

Another potentially useful form of peer interaction is peer assessment, whereby peers evaluate or grade each other’s work. Zundert et al (2010) provide a useful overview of peer assessment in their literature review ‘Effective peer assessment processes: research findings and future directions’. The overall consensus is that peer interaction in the form of peer assessment is useful to the students. However, forms of interaction within peer assessment vary. The term peer assessment can refer to students grading each others work or to students providing qualitative feedback on the performance of another student. The type of peer assessment which students engage in can impact the benefits experienced by the students.

Sung and colleagues (2003) found that psychology students were better able to come to agreement on the quality of their work after discussing their results with their peers and hearing their feedback. This study was conducted on a class of 34 psychology students who were given six weeks to each write a research proposal. Fellow students provided feedback on the proposals and the students had an opportunity to revise their work. Feedback benefited the students; the study reported that when the students revised their work after the peer discussion, their grades improved. This suggests that peer assessment is a useful form of peer interaction when peers provide feedback through discussion.

The use of peer interaction for improving academic performance is further supported by the work of Olson and colleagues (1990). Olson’s work is one of very view in the field to adopt a true experimental design. Students were divided into one of three learning groups – revision training with peer assessment, only peer assessment, or only revision training. Students had to complete a piece of written work, and then had the opportunity to revise their work after being exposed to the conditions of one of the three groups. The students in the peer assessment condition met with their peer partners twice a week for a month to discuss and revise their work, whereas the revision training group attended twice weekly revision instruction classes over the same time frame. The results revealed that the peer assessment group performed better than the revision group upon retest. Therefore, peer assessment had a positive effect on the quality of the students writing and was more useful than the revision classes alone.

Mixed Results...

Despite the positive results of peer assessment in the form of feedback discussion groups, peer assessment is not equally useful across all areas of peer interaction and learning. Particularly students can not accurately grade their peers' performance - studies have found mixed results over how accurate peers are at grading their fellow students compared to traditional assessment methods. Levine et al (2007) instructed 152 psychiatry students to assess their fellow students on their work. The students' assessments were compared with traditional forms of assessment including the National Board of Medical Examiners’ psychiatry subject test score and clinical grades. The study revealed a low to modest correlation between the mean peer assessment scores and the scores from the traditional methods. Modest correlations between scorings from peers and scores from traditional examination methods were also found in the work of Stefani (1994). In Stefani's study, 67 undergraduate students wrote a laboratory report, which was scored out of 100 by both peers and a tutor according to the same marking scheme. A comparison of the peer scoring and tutor scoring revealed a modest correlation. However, Hughes and Large (1993) reported finding a high correlation between peer and staff assessment scores when both peers and staff rated students performance in a presentation.

These mixed findings suggest that students can not be relied on to provide an accurate assessment of how well their peers performed, compared to the ratings given by staff. This finding highlights the importance of having a teacher, who is needed to help students gage their own ability. Therefore, the results suggest that peer interaction must not be the only interaction available to students. Peer interaction does not appear to be a reliable method of knowing how well a student has done in a piece of work.

When is Peer Assessment Useful?

Although not explicitly stated in the review paper, the designs of the successful versus the non-successful peer assessment set ups reveal that the key to peer assessment success lies in the opportunity for discussion between the group regarding feedback. Studies have revealed that peer assessment in the form of getting students to grade the work is less effective. However, fellow students can be very good at helping each other better understand why they achieved the grade that they did through feedback and debate.

Benefits are predominantly seen in the case of discussion groups, it is likely that these benefits are a consequence of the students having to think about their work and take on board other people’s views which makes the students form an argument and deeply think about their work. This argument is fitting with that of the papers discussed above, which argued that discussions make students form arguments to back their answers whilst also exposing them to other viewpoints which they consider. Providing explantations for reasoning has been repeatedly found to help students form a better understanding of their answers and question their beliefs when they are challenged. A deeper understanding of a topic is needed in order to defend and explain an argument to others, and peers provide a useful outlet for this.

Although students are not always accurate at grading their peers' work, this chance that peers may be wrong in their feedback advice, means that students question advice from peers more than advice from a teacher. The process of being challenged and working out if the other person is right or wrong is important in helping students better understand their work and is likely to be why peer assessment in the form of discussion, leads to improved scores on retest.

Thus, peer assessment is useful when it promotes discussion and consequently deeper learning.

Reciprocity Effects

Peer assessment has received criticism, as concern has been raised that students will demonstrate bias in their feedback response. Students' feedback could be affected by their interpersonal relationships with their peer groups. However, studies have discredited this concern. Research suggests that peer interaction in the form of peer assessment feedback is unlikely to be driven by reciprocity effects, i.e. students behaving with bias when providing feedback to their friends. Magin (2001) tested for reciprocity effects in a sample of medical students who were asked to conduct a project in small groups and then provide feedback on the performance of their peers. Reciprocity effects accounted for just 1% of variance in the peer assessment feedback.

Magin's findings further support peer assessment as a useful mode of peer interaction. The study's results suggest that students are in fact able to provide useful feedback to each other regardless of the social relationships between students.

Thinking Style

The successful use of peer assessment complicates when considering individual differences of the students, specifically their thinking style. Lin and colleagues (2001) found that the benefits of peer assessment in the form of discussion feedback on a piece of work varied depending on the thinking style of the student. The Thinking Style Inventory measured the thinking style of 58 students, who were categorised as being either a 'high executive thinker' or a 'low executive thinker'. High executive thinkers were defined as being willing to follow instructions whereas the low executive thinkers were seen as more creative and independent. Students who were high executive thinkers benefited equally from holistic or specific feedback, whereas low executive thinkers performed best when experiencing holistic feedback. This suggests that peer assessment feedback should be tailored to meet the needs of each individual, and specifically highlights that not all students will benefit equally from the peer interaction environment.

Optimum Conditions

The success of peer interaction in the form of peer assessment is dependent on several factors. Firstly, benefits of the feedback become apparent only when the students are given the opportunity to revise their work based on the assessment feedback they received for it. The students then need to be given adequate time to make the necessary changes to their work. It is beneficial to the students if the group size is kept relatively small, to facilitate active involvement in discussion. As mentioned previously, the form of feedback is important. For example, getting students to simply grade each others work does not provide benefits to the student, and further to this the grade may not be representative of the mark given by the teacher. Additionally, the students individual thinking style should be consider when deciding how best to facilitate peer feedback sessions in order to maximise benefits to the students' learning.

Overall, peer assessment in which students meet in groups and advise each other on their work, can be extremely beneficial to improving the students learning, and to improving their performance on retest.

Peer Interaction in Online Settings

Key paper - Swan, K. (2002). Building learning communities in online courses: The importance of interaction.

Summary

This study examines how peer interaction in virtual communication groups can facilitate learning. Virtual groups are a convenient method of communication in higher education, as they enable students to interact with one another without physical proximity. This allows students with busy timetables to engage in discussion even if finding a common meeting time is impossible. Many higher education courses provide online courses, where virtual communication is the main method of interaction between the student, the teacher and others in the course. The extensive information base offered by the Internet cannot support learning in itself, so online interaction is crucial to the success of students in these courses (Bork, 2001). This paper first evaluates the relationship between peer interactions, other factors such as course organization and success of learning, and then investigates the features of online discussion "communities". From this discussion, the researchers developed an equilibrium model of social presence in online discussion groups.

Key results in the paper

In traditional classrooms, immediacy between students and the teacher has been found to improve success in learning. (Christophel, 1990) Immediacy refers to the extent to which a teacher and a student engage each other in communication, with behaviors such as giving praise, scaffolding the contributions of different student's opinions during discussion, self-disclosure and humor all helping decrease the psychological distance between the student and teacher (Swan, 2002). Therefore, it is possible that in an online group, teacher presence may play an important role in establishing the community and encouraging ongoing interaction between students. Additionally, several studies suggest that peer interaction is not only of increased importance in online based learning, but also depends more on the online presence of a teacher to help structure and facilitate the discussions (Ruberg et al, 1996) The study developed the first of their two experiments to address the relationship between these factors; in which students in an online course were asked to rate their perceived levels of satisfaction, learning, activity, and interaction with both peers and their teacher. It was found that perceived interaction with both peers and teacher correlated with increased satisfaction and learning on the course. This suggests that peer interaction in an online setting is most effective when combined with a supervisory presence to help structure the interaction.

In light of this result, the researchers conducted a second experiment, to investigate the nature of online peer interaction more deeply. In particular, the paper aims to establish what sorts of interaction and discussion behaviors are important in building an online community which effectively facilitates learning. Social presence is thought to be of great importance in online communication, as it helps to establish immediate between peers and prevents individuals feeling isolated from the group (Swan, 2002). This experiment therefore looked to establish the effect of a variety of social presence establishing behaviors on the quality of online discussion. These are known as immediacy markers, and are categorized as affective, cohesive and interactive markers. Affective behaviors express emotion and beliefs, such as statements of self-disclosure, jokes and humor; cohesive behaviors encourage group participation and progression of group goals, and include discussion of the course at hand, addressing individuals by name and discussing plans for the group using "we"; and interactive behaviors are those that signal attention, such as agreement, advice and acknowledgement. Together, these immediacy markers help to establish a cohesive group and reduce psychological distance. The researchers analyzed the messages posted on a discussion forum by students of a web based course, and examined the use of affective, cohesive and interactive features of communication.

It was found that the participants used a greater degree of immediacy behavior, particularly acknowledgement of each other's messages, compared to traditional face-to-face discussions. This suggests that immediacy markers are used in online communication to compensate for the increased physical distance and prevent psychological distance. Additionally, direct cohesive contributions such as referring to the group as a whole and formally discussing the goals of the group tended to decrease over time, suggesting that as online groups become more established, they become less reliant on instructive aspects of discussion and are able to progress cohesively with a lower level of scaffolding.

Model - Equilibrium of Social Presence

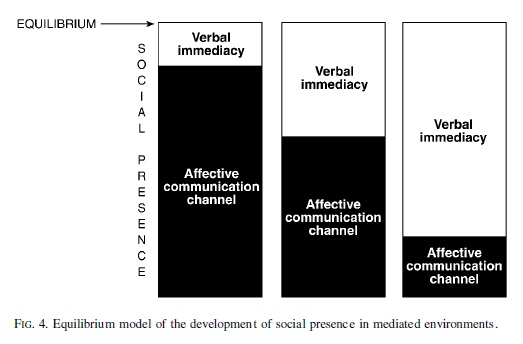

From this result, the researchers developed an equilibrium model of social presence. The model illustrates how immediacy behaviors as whole help to compensate in situations where affective communication channels are unavailable - such as group work which is carried out in exclusively web based discussions:

Conclusions of the study

Overall, the paper contributes well to the literature on peer interaction as it draws evidence based conclusions on several aspects of online peer communication. Firstly, it was found that although peer interaction is of great importance in the success of learning within online discussion groups, this works best when a supervisory presence such as a teacher is involved in the interaction, to help direct discussion to what is most beneficial to the course at hand. Secondly, the finding that cohesive interactions decrease over time suggests that groups attempt to tailor aspects of communication according to what is most beneficial to the community at each stage of group work - when the group is in an early stage, more attention is paid to establishing a cohesive community and directing the formation of group goals, whereas in later stages, the focus shifts to maintaining social presence and decreasing psychological distance between group members through interactive contributions. Finally, the equilibrium model provides a useful theoretical representation of the balance between social presence and the need for immediacy behavior in discussion. The model helps to illustrate one method by which peers communicating in an online setting may maintain a close social presence with others despite physical distance.

Peer Interaction in other online platforms

The Swan (2002) paper provides an analysis of how students in an online higher education course communicated via an online forum. This is a very useful platform to study as many courses use forums and message boards to organize group work, even when communication between students needn't be exclusively web-based and opportunities for face-to-face working exist. This emphasizes the importance of research in the area of online peer interaction in education, as it shows that factors such as convenience lead students to choose to engage in remote interaction with their peers over traditional discussion. One emerging platform for this is the use of wiki pages. In this case, students form small groups and create an informative webpage about the subject they are studying, which every member of the team is encouraged to contribute sections to, help to review and discuss content, and help edit and present the final submission.

A study by Augar et al (2004b). examined the wiki page task and its usefulness at promoting peer interaction. In this study, a group of university students were given a task which involved collaborating with one another to answer biographical questions, presenting the answers in a single wiki page. The goal of the study was to monitor the extent to which students engaged in the exercise, interacted with and responded to others in the group, and sustained communication over a period of time. This information was then compared to previous research by Augar et al (2004a), in which students were asked to prepare a short biography alone, post it on a forum, and then discuss the biographies of one another via the forum as a means of getting to know one another. This task was unsuccessful, as many students either did not attempt it at all, or posted one contribution directly before the deadline and did not engage in any real discussion (Augar et al, 2004a). In contrast, this study found that when this task was presented as a co-edited wiki exercise, almost all of the students contributed to the task and took part in ongoing discussions with one another over a period of two weeks. This study therefore suggests that wiki pages are a useful online platform for peer interaction, as they appear to encourage students to participate in discussions much more effectively than forums alone. As previous research has found that peer discussion enhances learning, it is possible that wiki based exercises also promote increased student learning of the topic they are used in, by facilitating interaction and discussion. However, this would be a good question for further research to address, as the Augar et al (2004b) study did not examine learning gains.

One area of education where peer interaction is especially useful is the teaching of language. Language learning is a very social process, as practise of conversation involves mimicking, responding to and receiving responses from others (Donato, 1994). In light of the research previously discussed, which suggests that students learn effectively from activities involving peer interaction, many language teachers have incorporated the theory into their classroom exercises. In this video, a teacher explains how students learning English as a second language in her class have benefited from one such activity:

Children learning English were taught how to solve science problems, and paired with a native English speaking classmate who they then tutored on how to solve the problem. This provided the learner children with a structured opportunity to practise conversing in English with their peers.

In conclusion, peer interaction can be extremely useful when it encourages students to ellaberate on their thoughts and take in opinions of others. Generating reasons for your answers enables students to process the material in greater depth and in doing so, this enhances the studens learning and understanding. Effectiveness of peer interaction varies depending on group, task and reward structure, and individual differences. Additionally students can not replace the teacher in terms of provinding grade feedback, although debate with other students regarding feedback can greatly improve retest performance. Additionally, with advanced technologies, peer interaction has been found to be vital for success in online learning communities. Therefore, peer interaction is generally very useful for promoting learning.

References

Azmitia, M. (1988). Peer interaction and problem solving: when are two heads better than one? Child Development, 59, 87-96.

Augar, N., Raitman, R. & Zhou, W. (2004a). From e-learning to virtual learning community: Bridging the gap. Paper presented at the International Conference on Web-Based Learning, Advances in WebBased Learning - ICWL 2004, Beijing

Augar, N., Raitman, R., and Zhou, W. (2004b). Teaching and learning online with wikis. In Beyond the comfort zone : proceedings of the 21st ASCILITE Conference, Perth, 5-8 December Perth, Australia, 5-8 December 2004, pp. 95-104.

Bork, A. (2001).What is needed for effective learning on the Internet? Educational Teaching and Society, 4(3).

Christophel, D. M. (1990). The relationships among teacher immediacy behaviours, student motivation, and learning. Communication Education, 39. 323 - 340.

Dillenbourg, P. (2002). Over-scripting CSCL: The risks of blending collaborative learning with instructional design. Three worlds of CSCL. Can we support CSCL?, 61-91.

Donato, R. (1994). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian approaches to second language research. Norwood, NJ: Ablex

Howe, C., McWilliam, D., & Cross, G. (2005). Chance favours only the prepared mind: Incubation and the delayed effects of peer collaboration. British Journal of Psychology, 96, 67-93.

Hughes, I. & Large, B. (1993). Staff and peer group assessment of oral communication skills. Studies in Higher Education. 18, 379-385.

King, A. (1990). Enhancing peer interaction and learning in the classroom through reciprocal questioning.American Educational Research Journal, 27, 664-687.Levine, R., Kelly, A., Karakoc, T. & Haidet, P. (2007). Peer evaluation in clinical clerkship: students' attitudes, experiences, and correlations with traditional assessments. Academic Psychiatry. 31, 19-24.

Lin, S., Liu, E. & Yuan, S. (2001). Web-bassed peer assessment: feedback for students with various thinking styles. Journal of computer assisted learning. 17, 420-432.

Magin, D. (2001). Reciprocity as a source of bias in multiple peer assessment of group work. Studies in Higher Education. 26, 53-63.

Olson, V. (1990). The revising process of sixth grade writers with and without peer feedback. Journal of Educational Research. 84, 22-29.

Smith, M. K., Wood, W. B., Adams, W. K., Wieman, C., Knight, J. K., Guild, N. & Su, T. T. (2009). Why peer discussion improves student performance on in-class concept questions. Science, 323, 122-124.

Sung, Y., Lin, C., Lee, C. & Chang, K. (2003). Evaluating proposals for experiments: an application of web-based self assessment and peer assessment. Teaching of Psychology. 30, 331-334.

Swan, K. (2002). Building learning communities in online courses: The importance of interaction. Education, Communication and Information, 2(1). 23 - 49.

Webb, N.M. (1989) "Peer interaction and learning in small groups" International Journal of Educational Research, vol.13 no.1 ch.2 pp.21–39

Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D. & Merrienboer,J. (2010). Effective peer assessment process: research findings and future directions. Learning and Instruction. 20, 270-279.