Summary

Participation in learning environments is thought to facilitate effective learning by considering learning in context so that learning takes on a new and relevant meaning for the learner. The learner is taking part in learning rather than just acquiring knowledge. Learning activities are not considered separately from the situated context within which they take place. Key phrases that describe participatory learning, such as "practice," "discourse" and "communication" suggest that the learner should be viewed as a person interested in participation in learning activities rather than in accumulating chunks of knowledge. Learning through participation has links with Vygotskian socio-cultural theory.

The importance of participation in learning environments was emphasised by Sfard's seminal paper, in which she describes the 'acquisition' and 'participation' metaphors for learning and that an effective learning environment should consider both in design. This paper has been widely cited as it encapsulated the essence of the debate that was on-going about which of the two perspectives had most merit, and offered a new approach of marrying the two (Elmholdt, 2003).

The move towards viewing participation as essential to learning was heralded by Lave and Wenger's Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation , which emphasized the idea of social practice as important but focused on participation as especially important in learning. In this work the idea of communities of practice (CoP) was outlined, which are groups of people who share a craft and/or a profession. The interest lay mainly outside of formal education environments although recently work has since been extended to also consider learning in the Higher Education (HE) environment (Morton, 2012). In HE using CoP as a model has become increasingly prevalent, specifically in designing practical elements of courses that reflect real workplace settings.

Contents

Traditionally, learning has been viewed as the transfer of knowledge from teacher to learner, however in the last few decades this view of learning has shifted. Nowadays, most researchers agree that knowledge not only exists in individual minds but also in the discourse and social relationships of, and between individuals (Jonassen & Land, 2000). Students are not students just while they are in the classroom. It is widely acknowledged that students learn and support each other both inside and outside the classroom, in fact, most learning in higher education occurs outside the classroom (Ramsden, 1992). Thus focus in recent years has been upon understanding the influence of participation learning in HE learning environments as participation models are used more widely in post-compulsory education than in schooling (Edwards, 2005).

What is participation as a mode of learning?

Many consider participation to be important as a mode of learning, as they believe that learning involves more than acquiring an understanding; it involves building an implicit understanding of knowledge and the context within which that knowledge is used. Learning by participation has strong ties with situativity theory, which focuses on learning in relation to the individual and the context (Barab and Duffy, 2000). Brown, Collins, & Duguid (1989) argued that knowing and doing are one and the same; that learning is always situated and developed through activity. Central to this theory is the contention that participation in practice constitutes learning and understanding. It is suggested that concepts should be conceived as tools, which can only be fully understood through use. Reinforcing this view, Greeno and Moore (1993) argued that situativity, or understanding meaning in context is fundamental in all cognitive activity. Learning through participation has also been likened to developing expertise (Edwards, 2005), where expertise is a capacity to interpret the complexity of aspects of the world and the ability to respond to that complexity.

The roots of participation learning.

Lave and Wenger's Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation was a seminal text in the development of a new paradigm in learning theory. It challenged the view of learning as a change in either the cognitive state or behavioural disposition of individuals, proposing instead, like situativity theorists, that learning is social and situated. Lave and Wenger's focus on participation was developed by considering a wide range of apprenticeship learning situations, through which they developed the idea of communities of practise. They assert that learning is best understood as not only arising from but, crucially, as beingparticipation in social practices. These practices take place within context and so create patterns of relationships that constitute participation. This is the community of practice.

The theory of communities of practise was grounded in workplace situations, rather than classroom situations, as the theory was developed in informal learning situations (Boylan, 2012). It has been argued that the communities of practise model may not be entirely applicable to formal education settings and may not be suitable for explaining the types of participations that occur in these settings (Boylan, 2012). Rommetveit (2003) notes that the difference is that in formal education the search is for ‘knowledge about’ whereas informal education is about learning how to act appropriately in situations. Nonetheless is may still be useful as a model to inform and transform pedagogical practise to encourage participation in these settings.

The Acquisition and Participation Metaphors.

A move in the educational literature towards emphasizing the importance of participation in learning led Sfard (1998) to writing her important paper urging the community to consider the importance of, what she named as, both the 'acquisition' and the 'participation' metaphor for learning. Sfard argued, there was a move away from the predominant 'acquisition' metaphor that had guided much of the practice in education towards a 'participation' metaphor in which knowledge is considered fundamentally situated in practice. Sfard's (1998) metaphors were the “most fundamental, primary levels of our thinking that bring to the open the tacit assumptions and beliefs that guide us” (pp.4), in other words, the form which learning was considered to take. She argues these are more useful to consider than theories as they exist at a more fundamental level that can guide assumptions. These were characterised as:

The importance of considering both of these metaphors is emphasized by Sfard, who stated that each is equally important and offers essential features for effective learning. Appreciating the importance of learning by participation should not lead to an abandonment of traditional teaching practices that involve imparting blocks of knowledge but should aim to combine the two.

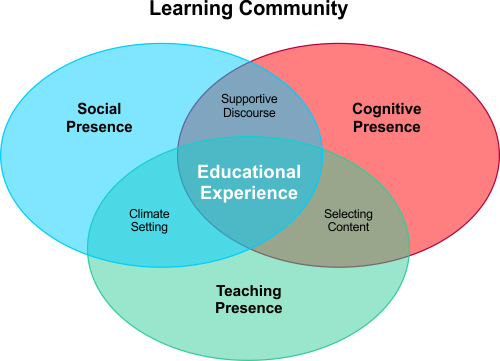

Lave and Wenger's Communities of Practise model has applied in an educational context through what has come to be known as Learning Communities. These are learning environments that are conducive to participatory learning (Smith, MacGregor, Matthews and Gabelnick, 2004), they define them as follows:

"A learning community is any one of a variety of curricular structures that link together several existing courses--or actually restructure the curricular material entirely--so that students have opportunities for deeper understanding and integration of the material they are learning, and more interaction with one another and their teachers as fellow participants in the learning enterprise."

Learning communities are useful tools in promoting academic success and student engagement, as they focus on emphasizing student-to-student and student-to-faculty interactions while providing intensive mentoring and advising for students. They have been hailed as important for improving student retention (Lardner and Malnarich, 2008). Shapiro and Levine (1999, p. 3) stated that successful learning communities share basic characteristics:

Organizing students and faculty into smaller groups

Encouraging the integration of the curriculum

Helping students establish academic and social support networks

Providing a setting for students to be socialized to the expectations of college

Bringing faculty together in more meaningful ways

Focusing faculty and students on learning outcomes

Providing a setting for community-based delivery of academic support programs

Offering a critical lens for examining the first-year experience

The importance of participation for effective learning as a theory has common elements with that of Vince Tinto's model for explaining student dropout rates from higher education. Student dropout is a widespread and substantial issue, recent estimates in the UK put the figure at around 27,000 students in the last year (news article), and considerable effort has been dedicated to combating it. Tinto's model first appeared in the literature in 1975 (Tinto, 1975) and has since gained widespread support. The key element of this theory is that of 'integration' both a social and academic nature (Tinto, 1987). In Tinto's model social integration involved, among others, elements of relationships with other students and also relationships with academics; academic integration involved elements of identifying with the role of a student and also identifying with the academic norms and values. It was suggested that level of social and academic integration, in reciprocal interaction with student commitment, would be strong predictors of student dropout. Tinto's model has found both support (Berger and Milem, 1999, Belch Gebel and Mass, 2001) and lack of support (Brunsden et al., 2000), in various contexts, although widespread agreement and consistency in methodology for testing this model would not seem to be apparent.

Participation in learning and Tinto's idea of integration would seem to be closely linked as one would seem to imply the other. It is possible that designing learning around the participatory element would also improve integration as a whole, as participatory learning encourages learners to become part of a community of learning. Learning communities have been praised as important for combating student dropout (Lardner and Malnarich, 2008). Future interventions aimed at combating student dropout could possibly include participatory elements in course design, as an effective higher education institute is the one that is concerned with student retention and student outcomes (Jenkins et al., 2006).

Adaption of Tinto's Model (1975) - focus on academic and social integration.

Similarities exist between the acquisition vs. participation contention and the objectivism vs. constructivism contention. The objective view of learning, sees knowledge as existing outside of individuals, so it can be transferred from teachers to students. Students learn what they hear and what they read. If a teacher explains abstract concepts well, students will learn those concepts, hence learning is successful when students can repeat what was taught. Constructivists believe that knowledge has personal meaning and is created by individual students. Learners construct their own knowledge by looking for meaning and order; they interpret what they hear, read, and see based on their previous learning and habits. Learning is successful when students can demonstrate conceptual understanding and construct their learning by engaging in mental processes (Vrasidas, 2000).

As has happened with the move from viewing learning solely as acquisition, Cobb (1994) noted that most researchers have abandoned objectivist views of learning and are moving towards constructivist and social theories of learning. However, in constructivist theories the emphasis lies on the individual constructing their learning, where as in participation learning, emphasis lies on the learning activities within a group.

While constructivism maintains that learners construct their own knowledge by looking for meaning and order; they interpret what they hear, read, and see based on their previous learning and habits, social constructivism emphasises that all cognitive functions including learning are dependent on interactions with others (e.g. teachers, peers, and parents). In this sense, learning is dependent on the qualities of a collaborative process within an educational community, which is situation specific and context bound (Schunk, 2012). According to social constructivism, learning must also be seen as more than the assimilation of new knowledge by the individual, but also as the process by which learners are integrated into a knowledge community.

In social constructivism theories, processes such as collaborative work and peer interaction provide a basis for learning (Wells, 2000), as knowledge is built and shared as a group. Collaborative learning allows learners to build a shared understanding of truth and knowledge through discourse. Sfard (1998) also noted the importance of discourse in participatory learning however, the emphasis lies more upon putting knowledge into context so that it takes on a new meaning for the learner. Although social interactions are important in participation in learning, the main aim of learning in a community of practise is putting knowledge into context for the learner in order to further understanding (Morton, 2012).

Participatory learning can be used in an array of different settings and includes a range of different methods employed to facilitate learning in individuals of any age. Learning itself is not only a key requisite within Education, but also within the business sector where new employees must be trained and adapt to novel practices in their line of work. In this section we go through the different applications of participatory learning in different contexts of higher education and discuss their effectiveness.

Online Application of Participatory Learning in Long-Distance Courses

Computer-based methods of learning have been shown to be of great use once outside the classroom when students have a chance to collaborate independently (Alavi, 1994; Brown & Palincsar, 1989). This type of learning method has also been utilized considerably by universities which could then offer a 'distance learning' alternative to a part/full-time degree. This type of course requires the student to have access to the internet in order to send and receive assignments, as well as being able to find relevant information and literature without being in proximity to the university (Berge & Collins, 1995). Due to the advances in technology and programming in the past decade, it is also possible to hold 'conferences' in either text form (by using applications such as msn messenger and social media sites providing a platform for chat functions) or via video calling (eg. Skype) with others. Research has found that this type of conference style collaborative learning is superior to 'correspondence style learning' or 'asynchronous communication' -for eg. emailing (Bullen, 2007; Hiltz et al, 2000). Many studies support the idea that online learning is most effective when there is collaboration between students and teachers (Bento & Schuster, 2003; Hrastinski, 2009; Leidner & Jarvenpaa, 1995; Webster & Hackley, 1997). One study found that online participation with other students about course materials could lessen the possibility of attaining a failing grade however the amount of participation did not have a profound effect on achieving higher grades (Davies & Graff, 2005). This however conflicts with other findings which showed that participation resulted in higher learning outcomes for some compared with the outcomes achieved from the traditional classroom approach to learning (Hiltz et al,2000).

Whether online learning is as 'successful' as face-to-face learning such as lectures and tutoring is still up for debate. It has been acknowledged that with online learning comes some facilitating factors such as an absence of time constraints (Warschauer, 1997; Davies & Graff, 2005) or what could be known as 'time-independence' (Bullen, 2007), as well as providing a means of comfortable participation for those who found it difficult in a classroom environment (Bullen, 2007; Harasim, 1990; Warschauer, 1997). However students who lack self-discipline and have not developed sufficient time management skills were found to suffer negatively from these factors. Time-independence instead resulted in more opportunity for procrastination, as well as students forgetting about the course due to attending to other tasks which demand a time and place (Bullen, 2007). This being said, Bullen (2007) pointed out that there are several influential factors such as student personality and learning experience which affect the effectiveness of both online and face-to-face learning - since the presence of assigned lectures does not guarantee attendance. It is essential that further research into these factors and the appropriate designs of courses is conducted (Harasim et al, 1995; Bullen, 2007).

Participatory Learning in a Classroom Setting

The traditional classroom setting is one that is most frequently used across education, from primary school to university. Literature on the subject of participatory learning has since evolved from the 'is participation important?' question to the 'how do we increase participation?' due to the bountiful amount of convincing empirical evidence confirming the former. Cooperative learning has been seen to encourage deep learning and improve critical thinking (Gokhale, 1995; Bower & Richards, 2006).

Studies have shown that participatory learning - which involves actively taking part in discussion with and collaborating with one's peers on a topic in order to achieve the same goals- is much more beneficial for students than working individually or competitively. It has been found to have a positive effect on achievement and retaining of information (Chi et al, 2008; Johnson & Johnson, 1986; 1992; Johnson et al, 1991; Lew et al, 1986; Mesch et al, 1988; Slavin, 1990) as well as having positive effects on students' motivation, enjoyment and independence (Augustine et al, 1989; Good et al, 1989; Slavin, 1990; Wood, 1987). Within higher education, this type of learning can be implemented by the assignment of group coursework, tutorials and by encouraging discussion in lectures.

Participatory learning can be broken up into different styles - cooperative and collaborative (Bruffee, 1995). Collaborative learning aims to shift the locus of authority to students during tasks giving a greater amount of autonomy to the group whereas cooperative learning aims to relinquish the competitive nature of a classroom by encouraging students to work with each other and increase accountability, all under a more structured environment. For example, a group of pupils in primary school working on a specifically assigned project during class whilst being supervised by a teacher would be classed as cooperative learning. Students in an undergraduate course who are told to create a project of their choice and are encouraged to have negotiations with the coordinator would be classed as collaborative. As evident from these examples, one type of learning technique is more suited to certain environments and student age than the other (Bruffee, 1995). Each one comes with its advantages and disadvantages. Cooperative learning increases individual accountability for one's work, however it does not allow for autonomy or for negotiation with the teacher or coordinator which can limit a student's development of independence. Collaborative learning may increase autonomy and encourage interdependence within students, however it neglects individual accountability for one's work. That being said, research into addressing this problem has been increasing as of recently, most notably the creation of wiki pages to assess a group's work which allowing collaborative learning without the downside of absences of accountability due to the logging system of the program (de Pedro Puente, 2007; Engstrom & Jewett, 2005; Judd et al, 2010; Trentin, 2008).

Despite the positive effects resulting from collaborative learning, previous studies have still advocated tutor-pupil discussions as being more effective than group participation in raising students' achievement (Bloom, 1984; Cohen et al, 1982). However a study by Chi et al (2008) found that participation with peers may still be as important as the presence of and interaction with a tutor. In this study, they investigated the effects of vicarious learning on achievement by video-recording a tutorial session and then presenting for their sample of students to view either individually, or in pairs. Results showed that by merely observing the tutorial with a peer, their levels of achievement were almost equal to that of those who received one-to-one tutoring. This therefore lead to questions as to the true contribution of a tutor in the classroom, whilst promoting the 'student-centred' hypothesis - that learning is primarily due to a student's contributions rather than a tutor's.

Learning Via Communities of Practice (CoP)

A community of practice, first proposed by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 2000), is described as "a collection of people who engage on an ongoing basis in some common endeavour" (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2006) and are created by individuals from the same domain (such as a group of engineers or artists) who wish to learn within this domain by collaborating with each other (Wenger, 2011). This approach has been most notably used by the business sector, whereby organisations employ this initiative by introducing a new employee to a pre-existing community of practice or by creating a new one in order for them to share, learn and acquire important knowledge relevant to that organisation. This can then benefit the organisation as it can aid in the improvement of business strategy due to this collective thinking, and it can also result in the expansion of said business because of this collaboration between a group of individuals with a combined vision (Wenger & Snyder, 2000).

Within higher education, this approach has become more frequently used and has been promoted as highly valuable for a student's learning as well as teachers - both present and preservice (Lea, 2005; Wenger & Snyder, 2000). Initially, within the education sector, the CoP approach was mainly for teachers. It provided those who had become newly integrated into the organization with peer-to-peer professional-development activities thereby increasing their performance and essentially their knowledge (Wenger & Snyder, 2000). However the main question is whether this approach can be applied to students. A study followed another possible implementation of this approach - used by Indiana University - which consisted of a program that required student teachers who wished to attain secondary teaching certification to merge themselves with a pre-existing community of secondary teachers for 2 to 4 years (Barab et al, 2002). This allowed them to gain exposure and experience to their future work environment in order to enable them to create effective learning systems within their classrooms after attaining certification. Also this practice-based approach has been seen to maintain and even increase motivation and enthusiasm in student teachers (Wilson et al, 1996) which have both been linked to higher quality instructional behaviour (Kunter et al, 2008) as well as increasing their students' intrinsic motivation allowing them to be more receptive and active learners (Patrick et al, 2000). Other courses in higher education provide these types of community-based opportunities for learning in order to acquaint and prepare their students with life beyond university. For example, within the University of Glasgow, undergraduate courses such as Business and Psychology encourage students to work together on assignments, to establish relationships between each other by organising class trips and also to engage independently with the outside community for coursework such as surveys and experiments (please see websites 1 & 2 for information on these degrees). Another study investigating the effects of exposing undergraduate student nurses to clinical environments during their course found that this community-based practice improved the students' self-efficacy (Ford-Gilboe et al, 1997) so it is evidently a useful tool for learning within higher education.

However it has been acknowledged that integrating this CoP approach to the foundations of institutions of higher education which have not done so already will take a very long time as it would influence a university's former education practices (Wenger, 2011). The university would no longer be centred around lectures and classes, they would instead be used as a service towards a greater understanding of the outside world. For those who have already established a CoP approach in some form during their course, it is essential that they provide the most efficient and relevant form of CoP opportunities to their students. One study found that medical students within a 4-year graduate course at Flinders University were given the option to work in either a regional hospital or a tertiary hospital based in Adelaide, Australia for their CoP learning (Worley et al, 2004). It had been assumed by the university that this opportunity for students to work in a tertiary hospital was superior to work in a regional hospital, and were expected to attain higher grades than those working more locally. This was seen to be a great misjudgement, as instead the regional group had improved their academic performance to a greater degree that the Adelaide group. Another piece of research also found that students within architectural courses involved in community-based practice sessions had less opportunities to perform expertise (Morton, 2012). Instead, the instructors carried out most of the important tasks themselves, therefore limiting the students' experiences with real life situations. Lastly, CoP opportunities such as this one at Flinders University cost money, however they were able to rely on grants and government funding to pay for these practices. Other universities may not have access to such funds as so may find it more difficult to use CoP within their curriculum, therefore compromising the effectiveness of their students' learning experience.

The participatory learning approach has its foundations laid in the constructivist learning theory (Shen et al, 2010), which comes with its drawbacks. Different learning techniques are necessary for those of different ages and current educational experience- there is no 'one size fits all' approach to learning, and participatory learning is only made most effective between mature students who are not complete novices (Jonassen, 1997; O'Loughlin, 1992).

The nature of autonomous 'discovery' adopted by some users of this approach has been argued against, with authors stating that 'pure discovery is not a method of instruction' and that 'guided discovery' is much more beneficial for novice learners who do not have enough experience and knowledge in the topics to operate independently and effectively (Kirschner et al, 2006; Mayer, 2004; Sweller, 1988). Mayer (2004) pointed out that there has been a tendency to use this approach to constructivist learning even when it is unsuitable for the context - whether it be in terms of the learner or the context (Boylan, 2010). Another criticism by Kirschner et al (2006) stated that "Any instructional theory that ignores the limits of working memory when dealing with novel information or ignores the disappearance of those limits when dealing with familiar information is unlikely to be effective".

The concepts of ‘participation’ and ‘practice’ have also been criticized for their interchangeable nature and ambiguity. An individual who is part of a community of specialists who observes their actions rather than performs analogous activities cannot be seen to be ‘practicing’ one’s skills, merely participating (Handley et al, 2006; Roberts, 2006). However some would argue that in fact those who take part in said activities without creating and developing social relationships within this community cannot be truly ‘practicing’ either, as the relationships between individuals in communities of practice are essential for the learning experience. Also, there’s the suggestion that as humans, we have an inherent sense of self which may create tensions within these communities since there is a limit to how much an individual can adapt and adjust without compromising their identities (Handley et al, 2006), therefore potentially weakening the effectiveness of CoP strategies for learning.

It has also been argued that a collaborative approach to learning is not as efficient in transferring knowledge as 'teacher-centred' learning (Coombs & Chng, 2002) and so can take more time to accomplish the same amount of learning. Time is very significant factor in higher education, since courses, lectures and tutorials are all under time constraints and it is necessary to transfer a vast amount of knowledge in the time given. This also brings to light that the use of the participatory approach is in danger of being overly subjective and only focussing on the strategies within participation, consequently neglecting the objective outcomes - such as being able to answer exam questions 'correctly', and the acquisition of knowledge (Sfard, 1998; Schell & Janicki, 2013).

Lave and Wenger's seminal text is available on Google books here.

Objectivism vs. Constructivism

A review of participation as a meaning for learning by Anne Edwards (2005) here.

Alavi, M. (1994). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: An empirical evaluation. MIS Quarterly, 18(2), 159–174.

Augustine, D.K., Gruber, K. D., & Hanson, L. R. (1989). Cooperation works! Educational Leadership, 47, 4-7.

Barab, S. A., & Duffy, T. (2000). From practice fields to communities of practice. Theoretical foundations of learning environments, 1, 25-55.

Belch, H. A., Gebel, M., & Maas, G. M. (2002). Relationship between student recreation complex use, academic performance, and persistence of first-time freshmen. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 38(2), 220-234.

Bento, R., & Schuster, C. (2003). Participation: The online challenge. In A. Aggarwal (Ed.), Web-based education: Learning from experience (pp. 156–164). Hershey, Pennsylvania: Idea Group Publishing.

Berge, Z. L., & Collins, M. P. (Eds.). (1995). Computer mediated communication and the online classroom: distance learning. Hampton Press.

Berger, J., & Milem, J. (1999). The role of student involvement and perceptions of integration in a causal model of student persistence. Research in Higher Education, 40, 641–664.

Bloom, B. S. (1984). The 2 sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4-16.

Bower, M., & Richards, D. (2006). Collaborative learning: Some possibilities and limitations for students and teachers. In Proceedings of the 23rd annual ascilite conference: Who’s learning? Whose technology.

Boylan, M. (2010). Ecologies of participation in school classrooms. Teaching and teacher education, 26(1), 61-70.

Brown, A. L., & Palincsar, A. S. (1989). Guided, cooperative and individual knowledge acquisition. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

Bruffee, K. A. (1995). Sharing our toys: Cooperative learning versus collaborative learning. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 27(1), 12-18.

Brunsden, V., Davies, M., Shevlin, M., & Bracken, M. (2000). Why do HE students drop out? A test of Tinto's model. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 24(3), 301-310.

Bullen, M. (2007). Participation and critical thinking in online university distance education. The Journal of Distance Education/Revue de l'Éducation à Distance, 13(2), 1-32.

Chi, M. T., Roy, M., & Hausmann, R. G. (2008). Observing tutorial dialogues collaboratively: Insights about human tutoring effectiveness from vicarious learning. Cognitive Science, 32(2), 301-341.

Cohen, P. A., Kulik, J. A., & Kulik, C. L. C. (1982). Educational outcomes of tutoring: A meta-analysis of findings. American educational research journal, 19(2), 237-248.

Davies, J., & Graff, M. (2005). Performance in e‐learning: online participation and student grades. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(4), 657-663.

de Pedro Puente, X. (2007). New method using Wikis and forums to evaluate individual contributions in cooperative work while promoting experiential learning:: results from preliminary experience. In Proceedings of the 2007 international symposium on Wikis (pp. 87-92). ACM.

Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2006). Communities of practice. ELL, 2, 683-685.

Edwards, A. (2005). Let's get beyond community and practice: the many meanings of learning by participating. Curriculum Journal, 16(1), 49-65.

Elmholdt, C. (2003). Metaphors for Learning: cognitive acquisition versus social participation. Scandinavian journal of educational research, 47(2), 115-131.

Engstrom, M. E., & Jewett, D. (2005). Collaborative learning the wiki way. TechTrends, 49(6), 12-15.

Ford-Gilboe, M., Laschinger, H. S., Laforet-Fliesser, Y., Ward-Griffin, C., & Foran, S. (1997). The effect of a clinical practicum on undergraduate nursing students' self-efficacy for community-based family nursing practice. The Journal of nursing education, 36(5), 212.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking.

Good, T. L., Reys, B. J., Grouws, D. A., & Mulryan, C. M.(1989). Using work groups in mathematics instruction. Educational leadership, 47, 56-60.

Greeno, J. G., & Moore, J. L. (1993). Situativity and symbols: Response to Vera and Simon. Cognitive Science, 17, 49-61.

Handley, K., Sturdy, A., Fincham, R., & Clark, T. (2006). Within and Beyond Communities of Practice: Making Sense of Learning Through Participation, Identity and Practice*. Journal of management studies, 43(3), 641-653.

Harasim, L. (1993). Collaborating in cyberspace: Using computer conferences as a group learning environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 3(2), 119-130.

Hiltz, S. R., Coppola, N., Rotter, N., Turoff, M., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2000). Measuring the importance of collaborative learning for the effectiveness of ALN: A multi-measure, multi-method approach. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 4(2), 103–125.

Hrastinski, S. (2009). A theory of online learning as online participation. Computers & Education, 52(1), 78-82.

Jenkins, D., Bailey, T.R., Crosta, P., Leinbach, J., Marshall, J., Soonachan, A., & Noy., M. V. (2006). What community college policies and practices are effective in promoting student success?A Study of High- and Low-Impact Institutions. New York: Community College Research Center, Columbia University.

Johnson, D.W., & Johnson, R. T. (1986). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1992). Positive interdependence: Key to effective cooperation. In R. Hertz-Lazarowitz & N. Miller (Eds.), Interaction in cooperative groups: The theoretical anatomy of group learning (pp. 174–199). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, D. W., Maruyama, G., Johnson, R., Nelson, D., & Skon, L. (1981). The effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic goal structures on achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 89, 41-62.

Jonassen, D.H. (1997). Instructional design model for well-structured and ill-structured problem-solving learning outcomes. Educational Technology: Research and Development 45 (1).

Jonassen, D. H., & Land, S. M. (2000). Preface. In D. H. Jonassen & S. M. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (pp. 3–9). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum

Judd, T., Kennedy, G., & Cropper, S. (2010). Using wikis for collaborative learning: Assessing collaboration through contribution. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(3), 341-354.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

Kunter, M., Tsai, Y. M., Klusmann, U., Brunner, M., Krauss, S., & Baumert, J. (2008). Students' and mathematics teachers' perceptions of teacher enthusiasm and instruction. Learning and Instruction, 18(5), 468-482.

Lardner, E., & Malnarich. G., (2008). New Era in Learning-Community Work: Why The Pedagogy of Intentional Integration Matters. Change Magazine Retrieved March 21st, 2013 from http://www.changemag.org/Archives/Back%20Issues/July-August%202008/full-new-era.html.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

Lea, M. (2005). Communities of practice’ in higher education: Useful heuristic or educational model? In D. Barton, & K. Trusting (Eds.), Beyond communities of practice: Language, power and social context (pp. 180–197). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leidner, D. E., & Jarvenpaa, S. L. (1995). The use of information technology to enhance management school education: A theoretical view. MIS Quarterly, 19(3), 265–291.

Lew, M., Mesch, D., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1986). Positive interdependence, academic and collaborative-skills group contingencies, and isolated students. American Educational Research Journal, 23(3), 476-488.

Mesch, D., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1988). Impact of positive interdependence and academic group contingencies on achievement. The Journal of social psychology, 128(3), 345-352.

Morton, J. (2012). Communities of practice in higher education: A challenge from the discipline of architecture. Linguistics and Education, 23(1), 100-111.

O’Loughlin, M. (1992) Rethinking Science Education: Beyond Piagetian Constructivism Toward a Sociocultural Model of Teaching and Learning, Journal of Research and Science Teaching, 29, 8, 791-820.

Patrick, B. C., Hisley, J., & Kempler, T. (2000). “What's everybody so excited about?”: The effects of teacher enthusiasm on student intrinsic motivation and vitality. The Journal of Experimental Education, 68(3), 217-236.

Roberts, J. (2006). ‘Limits to communities of practice’. Journal of Management Studies, 43, 3, 623– 39.

Rommetveit, R. (2003) On the role of ‘a Psychology of the Second Person in Studies of Meaning, Language and Mind’, Mind, Culture and Activity, 10(3), 205–18.

Schell, G., & Janicki, T. J. (2013). Online Course Pedagogy and the Constructivist Learning Model. Journal of the Southern Association for Information Systems, 1(1).

Sfard, A. (1998). On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educational researcher, 27(2), 4-13.

Shen, T., Wu, D., Archhpiliya, V., Bierbert, M., & Hiltz, R. (2010). Participatory Learning Approach: A research agenda. Technical report for Information Systems Department. New Jersey: Institute of Technology.

Slavin, R. E. (1990). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Smith, B. L., MacGregor, J., Matthews, R. S., & Gabelnick, F. (2004). Learning Communities: Reforming Undergraduate Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive science, 12(2), 257-285.

Tinto,V. (1975) "Dropout from Higher Education: A Theoretical Synthesis of Recent Research" Review of Educational Research vol.45, pp.89-125.

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. University of Chicago Press, 5801 S. Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637

Trentin, G. (2008). Using a wiki to evaluate individual contribution to a collaborative learning project. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25(1), 43-55.

Vrasidas, C. (2000). Constructivism versus objectivism: Implications for interaction, course design, and evaluation in distance education. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 6(4), 339-362.

Wells, G. (2000). Dialogic inquiry in education. Vygotskian perspectives on literacy research. Constructing meaning through collaborative inquiry, 51-85.

Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: theory and practice. Modern Language Journal, 8, 4, 470–481.

Webster, J., & Hackley, P. (1997). Teaching effectiveness in technology-mediated distance learning. Academy of Management Journal, 40(6), 1282–1309.

Wenger, E. (2011). Communities of practice: A brief introduction.

Wenger, E. C., & Snyder, W. M. (2000). Communities of practice: The organizational frontier. Harvard business review, 78(1), 139-146.

Wood, K. D.(1987). Fostering cooperative learning in the middle and secondary level classrooms. Journal of Reading, 31, 10-18.

Worley, P., Esterman, A., & Prideaux, D. (2004). Cohort study of examination performance of undergraduate medical students learning in community settings. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 328(7433), 207.