Martin J. Pickering & Simon Garrod1

ABSTRACT: 214 words

MAIN TEXT: 13836

REFERENCES: 2781

ENTIRE TEXT: 16993

TOWARD A MECHANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY OF DIALOGUE

Martin J. Pickering

University of Edinburgh

Department of Psychology

7 George Square

Edinburgh EH8 9JZ

United Kingdom

Email: Martin.Pickering@ed.ac.uk

http://www.psy.ed.ac.uk/Staff/academics.html#PickeringMartin

Simon Garrod

University of Glasgow

Department of Psychology

58 Hillhead Street

Glasgow G12 8QT

United Kingdom

Email: simon@psy.gla.ac.uk

http://staff.psy.gla.ac.uk/~simon

Short Abstract

Traditional mechanistic accounts of language processing derive almost

entirely from the study of monologue. By contrast we propose a mechanistic

account of dialogue. The account assumes that, in dialogue, production

and comprehension become tightly coupled and this coupling leads to the

automatic alignment of linguistic representations at many levels. The interactive

alignment process greatly simplifies production and comprehension in dialogue.

It supports a simple interactive inference mechanism that enables dialogue

participants to keep track of their common ground. It enables the development

of local dialogue routines that greatly simplify language processing. Finally,

it explains the origins of self-monitoring in production.

Long Abstract

Traditional mechanistic accounts of language processing derive almost

entirely from the study of monologue. Yet, the most natural and basic form

of language use is dialogue. As a result, these accounts offer limited

and inadequate theories of the mechanisms that underlie language processing

in general. We propose a mechanistic account of dialogue and use

it to derive a number of predictions about basic language processes. The

account assumes that, in dialogue, production and comprehension become

tightly coupled and this coupling leads to the automatic alignment of linguistic

representations at many levels. This interactive alignment process greatly

simplifies production and comprehension in dialogue as compared to monologue.

After considering the evidence for the interactive alignment model, we

concentrate on three aspects of processing that follow from it. First,

it supports a simple interactive inference mechanism that enables dialogue

participants to keep track of their common ground without having to explicitly

model their partner’s beliefs. Second, it enables the development of local

dialogue routines that greatly simplify language processing. Third, the

alignment model makes interesting predictions about the nature of self-monitoring

during production. Finally, we consider the need for a grammatical framework

that can account for language in dialogue which is sufficiently flexible

to deal with language fragments yet precise enough to support a coherent

semantics.

Keywords: dialogue, language processing, common ground, routines,

language production, monitoring.

1. INTRODUCTION

Psycholinguistics aims to describe the psychological processes underlying

language use. The most natural and basic form of language use is dialogue:

Every language user, including young children and illiterate adults, can

hold a conversation, yet reading, writing, preparing speeches and even

listening to speeches are far from universal skills. Therefore a central

goal of psycholinguistics should be to provide an account of the basic

processing mechanisms that are employed during natural dialogue.

Currently, there is no such account. Existing mechanistic accounts are

concerned with the comprehension and production of isolated words or sentences,

or with the processing of texts in situations where no interaction is possible,

such as in reading. In other words, they rely almost entirely on monologue.

Thus, theories of basic mechanisms depend on the study of a derivative

form of language processing. We argue that such theories are limited and

inadequate accounts of the general mechanisms that underlie processing.

In contrast, this paper outlines a mechanistic theory of language processing

that is based on dialogue, but which applies to monologue as a special

case.

1.1 Why does mechanistic psycholinguistics concentrate on monologue?

Why has traditional psycholinguistics ignored dialogue? There are probably

two main reasons, one practical and one theoretical. The practical reason

is that it is generally assumed to be too hard or impossible to study,

given the degree of experimental control necessary. Studies of language

comprehension are fairly straightforward in the experimental psychology

tradition — words or sentences are stimuli that can be appropriately controlled

in terms of their characteristics (e.g., frequency) and presentation conditions

(e.g., randomized order). Until quite recently it was also assumed that

imposing that level of control in many language production studies was

impossible. Thus, Bock (1996) points to the problem of "exuberant responsing"

— how can the experimenter stop subjects saying whatever they want? However,

it is now regarded as perfectly possible to control presentation so that

people produce the appropriate responses on a high proportion of trials,

even in sentence production (e.g., Bock, 1986a; Levelt & Massen, 1981).

Contrary to many people’s intuitions, the same is true of dialogue.

For instance, Branigan, Pickering, and Cleland (2000) showed effects of

the priming of syntactic structure during language production in dialogue

that were exactly comparable to the priming shown in isolated sentence

production (Bock, 1986b) or sentence recall (Potter & Lombardi, 1998).

In Branigan et al.’s study, the degree of control of independent and dependent

variables was no different from in Bock’s study, even though the experiment

involved two participants engaged in a dialogue rather than one participant

producing sentences in isolation. Similar control is exercised in studies

by Clark and colleagues (e.g., Brennan & Clark, 1996; Brennan &

Schober, 2001;Wilkes-Gibbs & Clark, 1992; also Horton & Keysar,

1996). Well-controlled studies of language production in dialogue may require

some ingenuity, but such experimental ingenuity has always been a strength

of psychology.

The theoretical reason is that psycholinguistics has derived most of

its predictions from generative linguistics, and generative linguistics

has developed theories of isolated, decontextualized sentences that are

used in texts or speeches — in other words, in monologue. In contrast,

dialogue is inherently interactive and contextualized: Each interlocutor

both speaks and comprehends during the course of the interaction; each

interrupts both others and herself; on occasion two or more speakers collaborate

in producing the same sentence (Coates, 1990). So it is not surprising

that generative linguists commonly view dialogue as being of marginal grammaticality,

contaminated by theoretically uninteresting complexities. Dialogue sits

ill with the competence/performance distinction assumed by most generative

linguistics (Chomsky, 1965), because it is hard to determine whether a

particular utterance is "well-formed" or not (or even whether that notion

is relevant to dialogue). Thus, linguistics has tended to concentrate on

developing generative grammars and related theories for isolated sentences;

and psycholinguistics has tended to develop processing theories that draw

upon the rules and representations assumed by generative linguistics. So

far as most psycholinguists have thought about dialogue, they have tended

to assume that the results of experiments on monologue can be applied to

the understanding of dialogue, and that it is more profitable to study

monologue because it is "cleaner" and less complex than dialogue. Indeed,

they have commonly assumed that dialogue simply involves chunks of monologue

stuck together.

The main advocate of the experimental study of dialogue is Herbert Clark.

However, his primary focus is on the nature of the strategies employed

by the interlocutors rather than basic processing mechanisms. Clark (1996)

contrasts the "language-as-product" and "language-as-action" traditions.

The language-as-product tradition is derived from the integration of information-processing

psychology with generative grammar and focuses on mechanistic accounts

of how people compute different levels of representation. This tradition

has typically employed experimental paradigms and decontextualized language;

in our terms, monologue. In contrast, the language-as-action tradition

emphasizes that utterances are interpreted with respect to a particular

context and takes into account the goals and intentions of the participants.

This tradition has typically considered processing in dialogue using apparently

natural tasks (e.g., Clark, 1992; Fussell & Krauss, 1992). Whereas

psycholinguistic accounts in the language-as-product tradition are admirably

well-specified, they are almost entirely decontextualized and, quite possibly,

ecologically invalid. On the other hand, accounts in the language-as-action

tradition rarely make contact with the basic processes of production or

comprehension, but rather present analyses of psycholinguistic processes

(e.g., the formulation and use of common ground; Clark, 1985,1996; Clark

& Marshall, 1981) that are closely akin to rational analyses or ideal-observer

models (Anderson, 1990; Chater & Oaksford, 1999; Legge, Klitz, &

Tjan, 1997).

This dichotomy is a reasonable historical characterization. Almost all

mechanistic theories happen to be theories of the processing of monologue;

and theories of dialogue are almost entirely couched in intentional non-mechanistic

terms. But this need not be. The goals of the language-as-product tradition

are valid and important; but researchers concerned with mechanisms should

investigate the use of contextualized language in dialogue.

In this paper we propose a mechanistic account of dialogue and use it

to derive a number of predictions about basic language processing. The

account assumes that in dialogue, production and comprehension become tightly

coupled in a way that leads to the automatic alignment of linguistic representations

at many levels. This process greatly simplifies production and comprehension

in dialogue as compared to monologue. Sections 2 and 3 introduce the interactive

alignment model and discuss the evidence for it. Sections 4, 5, and 6 then

consider three aspects of processing that follow from alignment: interactive

inference, establishment of routines, and self-monitoring. Finally, Section

7 considers how to formulate a linguistic framework that is consistent

with this account.

2. THE NATURE OF DIALOGUE AND THE ALIGNMENT OF REPRESENTATIONS

Table 1 shows a transcript of a conversation between two players in

a co-operative maze game (Garrod & Anderson, 1987). In this extract

one player A is trying to describe his position to his partner

B

who

is viewing the same maze on a computer screen in another room.

Table 1. Example dialogue taken from Garrod and Anderson (1987).

1-----B: .... Tell me where you are?

2-----A: Ehm : Oh God (laughs)

3-----B: (laughs)

4-----A: Right : two along from the bottom one up:*

5-----B: Two along from the bottom, which side?

6-----A: The left : going from left to right in the second box.

7-----B: You're in the second box.

8-----A: One up :(1 sec.) I take it we've got identical

mazes?

9-----B: Yeah well : right, starting from the left, you're

one along:

10----A: Uh-huh:

11----B: and one up?

12----A: Yeah, and I'm trying to get to ...

[ 28 utterances later ]

41----B: You are starting from the left, you're one along,

one up?(2 sec.)

42----A: Two along : I'm not in the first box, I'm in the second

box:

43----B: You're two along:

44----A: Two up (1 sec.) counting the : if you take :

the first box as being one up :

45----B: (2 sec.) Uh-huh :

46----A: Well : I'm two along, two up: (1.5 sec.)

47----B: Two up ? :

48----A: Yeah (1 sec.) so I can move down one:

49----B: Yeah I see where you are:

* The position being described in the utterances shown in bold is

highlighted with an arrow in Figure 1. Colons mark noticeable pauses of

less than 1 second.

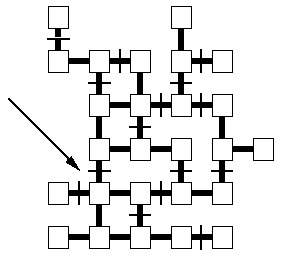

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the maze being described in

the conversation shown in Table 1. The arrow points to the position being

described by the utterances marked in bold in the table.

At first glance the language looks disorganized. According to standard

linguistics, many of the utterances are not grammatical sentences (e.g.,

only one of the first six contains a verb). There are occasions when production

of a sentence is shared between speakers, as in (7-8) and (43-44). It often

seems that the speakers do not know how to say what they want to say. For

instance, A describes the same position quite differently in (4),

"two along from the bottom one up," and (46), "two along, two up."

In fact the sequence is quite orderly so long as we assume that dialogue

is a joint activity (Clark, 1996; Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986). In other

words, it involves cooperation between interlocutors in a way that allows

them to sufficiently understand the meaning of the dialogue as a whole;

and this meaning results from these joint processes. In Lewis’s (1969)

terms, dialogue is a game of cooperation, where both participants "win"

if both understand the dialogue, and neither "wins" if one or both do not

understand.

Conversational analysts argue that dialogue turns are linked across

interlocutors (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973). A question, such as (1) "Tell

me where you are?", calls for an answer, such as (3) "Two along from the

bottom and one up." Even a statement like (4) "Right, two along from the

bottom two up," cannot stand alone. It requires either an affirmation or

some form of query, such as (5) "Two along from the bottom, which side?"

(Linnell, 1998). This means that production and comprehension processes

become coupled. B produces a question and expects an answer

of a particular type; A hears the question and has to produce an

answer of that type. For example, after saying "Tell me where you are?"

in (1), B has to understand "two along from the bottom one up" in

(4) as a reference to A’s position on the maze; any other interpretation

is ruled out. Furthermore, the meaning of what is being communicated depends

on the interlocutors’ agreement or consensus rather

than on dictionary meanings (Brennan & Clark, 1996) and is subject

to negotiation (Linnell, 1998, p.74). Take for example utterances (4-11)

in the fragment shown above. In utterance (4), A describes his position

as "Two along from the bottom and one up," but the final interpretation

is only established at the end of the first exchange when consensus is

reached on a rather different description by B (9-11) "You're one

along […] one up?" These examples demonstrate that dialogue is far more

coordinated than it might initially appear.

At this point, we should distinguish two notions of coordination that

became rather confused in the literature. According to one notion (Clark,

1985), interlocutors are coordinated in a successful dialogue just as participants

in any successful joint activity are coordinated (e.g., ballroom dancers,

lumberjacks using a two-handed saw). According to the other notion, coordination

occurs when interlocutors share the same representation at some level (Branigan

et al., 2000; Garrod & Anderson, 1987).To remove this confusion, we

refer to the first notion as coordination and the second as alignment.

Dialogue is a coordinated behavior (just like ballroom dancing). However,

the linguistic representations that underlie coordinated dialogue come

to be aligned, as we claim below.

We now argue three points: (1) that alignment of situation models (Zwaan

& Radvansky, 1998) is basic to successful dialogue and brings about

many desirable properties (e.g., understanding of how the interlocutor

is likely to react to information); (2) that the way that alignment of

situation models is achieved is by a primitive mechanism that produces

alignment at other levels of representation (lexical, syntactic, etc.)

and by interconnections between the levels; and (3) that another primitive

mechanism allows interlocutors to repair representations interactively.

This process of alignment is essentially resource-free and does not depend

on modeling the interlocutor’s mental state. More sophisticated strategies

for such "other modeling" are of course used on occasion, but do not form

part of the basic process of alignment. On this basis, we propose a general

interactive alignment account of dialogue.

2.1 Alignment of situation models is central to successful dialogue

In successful dialogue, interlocutors develop aligned situation models

(Johnson-Laird, 1983; Sanford & Garrod, 1981; van Dijk & Kintsch,

1983; Zwaan & Radvansky, 1998). In Garrod and Anderson (1987), players

aligned on particular spatial models of the mazes being described. Some

pairs of players came to refer to locations using expressions like right

turn indicator, upside down T shape, or L

on its side. These speakers represented the maze as an arrangement

of patterns or figures. In contrast, the pair illustrated in the

dialogue in Table 1 aligned on a model in which the maze was represented

as a network of paths linking the points to be described to prominent

positions on the maze (e.g., the bottom left corner). Pairs often developed

quite idiosyncratic spatial models, but both interlocutors developed the

same model (Garrod & Anderson, 1987; Garrod & Doherty, 1994; see

also Markman & Makin, 1998).

Alignment of situation models is not necessary in principle for

successful communication. It would be possible to communicate successfully

by representing one’s interlocutor’s situation model, even if that model

were not the same as one’s own. For instance, one player could represent

the maze according to a figure scheme but know that their partner

represented it according to a path scheme, and vice versa. But this

would be wildly inefficient as it would require maintaining two underlying

representations, one for producing one’s own utterances and the other for

comprehending one’s interlocutor’s utterances. Even though communication

might work in such cases, it is unclear whether we would claim that the

people understood the same thing. More critically, it would be computationally

very costly to have fundamentally different representations. In contrast,

if the interlocutors’ representations are basically the same, there is

no need for listener modelling.

Under some circumstances storing the fact that one’s interlocutors represent

the situation differently than oneself is necessary (e.g., in deception,

or when trying to communicate to one interlocutor information that one

wants to conceal from another). But even in such cases, many aspects of

the representation will be shared (e.g., I might lie about my location,

but would still use a figural representation to do so if that was what

you were using). Additionally, it is clearly tricky to perform such acts

of deception or concealment (Clark & Schaefer, 1987). These involve

sophisticated strategies that do not form part of the basic process of

alignment, and are costly, because they require the speaker to concurrently

develop two representations.

Of course, interlocutors need not entirely align their situation models.

In any conversation where information is conveyed, the interlocutors must

have somewhat different models, at least before the end of the conversation.

In cases of partial misunderstanding, conceptual models will not be entirely

aligned. In (unresolved) arguments, interlocutors have representations

that cannot be identical. But they must have the same understanding of

what they are discussing in order to disagree about a particular aspect

of it (e.g., Sacks, 1987). For instance, if two people are arguing the

merits of the Conservative vs. the Labour parties for the U.K. government,

they must agree about who the names refer to, roughly what the politics

of the two parties are, and so on, so that they can disagree on their evaluations.

In Lewis’s terms, such interlocutors are playing a game of cooperation

with respect to the situation model (e.g., they succeed insofar as their

words refer to the same entities), even though they may not play such a

game at other "higher" levels (e.g., in relation to the argument itself).

Therefore, we assume that successful dialogue involves approximate alignment

at the level of the situation model at least.

2.2 Achieving alignment of situation models

In theory, interlocutors could achieve alignment of their models through

explicit negotiation, but in practice they normally do not (Brennan &

Clark, 1996; Garrod & Anderson, 1987). It is quite unusual for people

to suggest a definition of an expression and obtain an explicit assent

from their interlocutor. Instead, "global" alignment of models seems to

result from "local" alignment at the level of the linguistic representations

being used.

This was pointed out by Garrod and Anderson (1987) in relation to their

principle of output/input coordination. They noted that in the maze game

task speakers closely matched the lexical, semantic, and pragmatic choices

that they had just encountered as listeners. In other words, their outputs

tended to match their inputs. As the interaction proceeded, the two interlocutors

therefore came to align the representations used for generating output

with the representations used for interpreting input. This points to a

mechanism in which the combined system (i.e., the interacting dyad) is

completely stable only if both subsystems (i.e., speaker A’s representation

system and speaker B’s representation system) are aligned. In other

words, the dyad is only in equilibrium when what A says is consistent

with B’s currently active lexical, semantic, and pragmatic representation

of the dialogue and vice versa (see Garrod & Clark, 1993). Thus, because

the two parties to a dialogue produce aligned language, the underlying

linguistic representations also tend to become aligned. We shall argue

that alignment is more general than Garrod and Anderson suggested. First,

it occurs at other levels (e.g., the syntactic). More fundamentally, alignment

at one level "percolates" through to produce alignment at other levels,

and that this process leads to alignment at the level of the situation

model (see Section 2.2.2). This process is essentially resource-free and

automatic.

Hence, we suggest that in dialogue representations become aligned at

many linguistic levels, such as the semantic, lexical, and syntactic, and

that this leads to alignment at the critical level of the situation model.

We shall argue that such aligned processing has far reaching implications

for everything from lexical and syntactic analysis to discourse inference

in dialogue. We also make it clear that dialogue involves more sophisticated

strategies as well as alignment, but these strategies are not primitive

mechanisms (and we return to them in Section 4.2).

2.2.1 Evidence for alignment at other levels

Dialogue transcripts are full of repeated linguistic elements and structures

indicating alignment at various levels (Aijmer, 1996; Schenkein, 1980;

Tannen, 1989). Alignment of lexical processing during dialogue was specifically

demonstrated by Garrod and Anderson (1987) as in the extended example in

Table 1 (see also Garrod & Clark, 1993; Garrod & Doherty, 1994),

and by Clark and colleagues (Brennan & Clark, 1996; Wilkes-Gibbs &

Clark, 1992). These latter studies show that interlocutors tend to develop

the same set of referring expressions to refer to particular objects and

that the expressions become shorter and more similar on repetition

with the same interlocutor and are modified if the interlocutor changes.

Levelt and Kelter (1982) found that speakers tended to reply to "What

time do you close?" or "At what time do you close" (in Dutch) with a congruent

answer (e.g., "Five o’clock" or "At five o’clock"). This alignment may

be syntactic (repetition of phrasal categories) or lexical (repetition

of at). Branigan et al. (2000) found clear evidence for syntactic

alignment in dialogue. Participants took it in turns to describe pictures

to each other (and to find the appropriate picture in an array). One speaker

was actually a confederate of the experimenter and produced scripted responses,

such as "the cowboy offering the banana to the robber" or "the cowboy offering

the robber the banana." The syntactic structure of the confederate’s description

strongly influenced the syntactic structure of the experimental subject’s

description. Their work extends "syntactic priming" work to dialogue: Bock

(1986b) showed that speakers tended to repeat syntactic form under circumstances

in which alternative non-syntactic explanations could be excluded (Bock,

1989; Bock & Loebell, 1990; Bock, Loebell, & Morey, 1992; Hartsuiker

& Westerberg, 2000; Pickering & Branigan, 1998; Potter & Lombardi,

1998; Smith & Wheeldon, 2001).

If syntactic alignment is due, in part, to the interactional nature

of dialogue, then the degree of syntactic alignment should reflect the

nature of the interaction between speaker and listener. As Clark and Schaeffer

(1987; see also Schober & Clark, 1989; Wilkes-Gibbs & Clark, 1992)

have demonstrated, there are basic differences between addressees and other

listeners. So we might expect stronger alignment for addressees than for

other listeners. To test for this, Branigan, Pickering, and Cleland (2001)

had two speakers take it in turns to describe cards to a third person,

so the two speakers overheard but did not speak to each other. Priming

occurred under these conditions, but it was weaker than when two speakers

simply responded to each other. Hence, syntactic alignment is affected

by speaker participation in dialogue.

Alignment also occurs at the level of articulation. It has long been

known that as speakers repeat expressions, articulation becomes increasingly

reduced (i.e., the expressions are shortened and become more difficult

to recognize when heard in isolation; Fowler & Housum, 1987). However,

Bard et al. (2000) found that reduction was just as extreme when the repetition

was by a different speaker in the dialogue as it was when the repetition

was by the original speaker. In other words, whatever is happening to the

speaker’s articulatory representations is also happening to their interlocutor’s.

There is also evidence that interlocutors align accent and speech rate

(Giles, Coupland, & Coupland, 1992; Giles & Powesland, 1975).

Finally, there is some evidence for alignment in comprehension. Levelt

and Kelter (1982, Experiment 6) found that people judged question-answer

pairs involving repeated form as more natural than pairs that did not;

and that the ratings of naturalness were highest for the cases where there

was the strongest tendency to repeat form. This suggests that speakers

prefer their interlocutors to respond with an aligned form. Garrod and

Anderson (1987) also found that players in the maze game would query descriptions

from an interlocutor that did not match their own previous descriptions

(see Section 4 below). In other words, the listener is guided and constrained

by her own recent contributions as a speaker. However, there is still little

evidence concerned with the "microstructure" of comprehension in dialogue

(as opposed to gross findings such as that comprehension is easier for

interlocutors than overhearers; Schober & Clark, 1989).

2.2.2 Alignment at one level leads to alignment at another

So far, we have concluded that successful dialogue leads to the development

of both aligned situation models and aligned representations at all other

linguistic levels. There are good reasons to believe that this is not coincidental,

but rather that aligned representations at one level lead to aligned representations

at other levels.

Consider the following two examples of influences between levels. First,

Garrod and Anderson (1987) found that once a word had been introduced with

a particular interpretation it was not normally used with any other interpretation

in a particular stretch of maze-game dialogue. For instance, the word row

could refer either to an ordered set of levels (e.g., with descriptions

containing an ordinal like "I’m on the fourth row") or to unordered sets

of levels (e.g., with descriptions that do not contain ordinals like "I’m

on the bottom row").2 Speakers

who had adopted one of these uses of row and needed to refer

to the other would introduce a new term, such as line or level.

Thus, they would talk of the fourth row and the bottom line,

but not the fourth row and the bottom row. In other words,

aligned use of a word seemed to go with a specific aligned interpretation

of that word. Restricting usage in this way allows dialogue participants

to assume quite specific unambiguous interpretations for expressions. Furthermore,

if a new expression is introduced they can assume that it would have a

different interpretation from a previous expression, even if the two expressions

are "dictionary synonyms." This process leads to the development of a lexicon

of expressions relevant to the dialogue (see Section 5). What interlocutors

are doing is acquiring new senses for words or expressions. To do this,

they use the principle of contrast just like children acquiring language

(e.g., E.V. Clark, 1993).

Second, it has been shown repeatedly that priming at one level can lead

to more priming at other levels. Specifically, syntactic alignment (or

"syntactic priming") is enhanced when more lexical items are shared. In

Branigan et al.’s (2000) study, the stooge produced a description using

a particular verb (e.g., the nun giving the book to the clown).

Some experimental subjects then produced a description using the same verb;

whereas other subjects produced a description using a different verb. Syntactic

alignment was considerably enhanced if the verb was repeated. Thus, interlocutors

do not align representations at different linguistic levels independently.

Likewise, Cleland and Pickering (2001) found people tended to produce noun

phrases like the sheep that’s red as opposed to the red sheepmore

often after hearing the goat that’s red than after the book that’s

red. This demonstrates that semantic relations between lexical items

enhance syntactic priming.

These effects can be modeled in terms of a lexical representation outlined

in Pickering and Branigan (1998). A node representing a word (i.e., its

lemma; Levelt, Roelofs, & Meyer, 1999; cf. Kempen & Huijbers, 1983)

is connected to nodes that specify its syntactic properties. So, the node

for give is connected to a node specifying that it can be used with

a noun phrase and a prepositional phrase. Processing giving the book

to the clown activates both of these nodes and therefore makes them

both more likely to be employed subsequently. However, it also strengthens

the link between these nodes, on the Hebbian principle that coactivation

strengthens association. Thus, the tendency to align at one level, such

as the syntactic, is enhanced by alignment at another level, such as the

lexical. Cleland and Pickering’s finding demonstrates that exact repetition

at one level is not necessary: the closer the relationship at one level

(e.g., the semantic), the stronger the tendency to align at the other (e.g.,

the syntactic). Note that we can make use of this tendency to determine

which specific levels are linked.

3. THE INTERACTIVE ALIGNMENT MODEL OF DIALOGUE PROCESSING

Aligned language processing is difficult to accommodate within a one-way

communication model of the kind assumed by current theories of production

and comprehension. In such models, the transfer of information between

producers and comprehenders takes place via decoupled production and comprehension

processes. The speaker (or writer) formulates an utterance on the basis

of her representation of the situation. In turn, the listener (or reader)

infers what the speaker (or writer) intended on the basis of his

autonomous representation of the situation. So, from a processing point

of view, speakers and listeners act in isolation. The only link between

the two is in the information conveyed by the utterances themselves (Cherry,

1956); see Fig. 2. In this autonomous transmission account,

only the final representation (i.e., sound) is "accessible." Each act of

transmission is treated as a discrete stage, with a particular unit being

encoded into sound by the speaker, being transmitted as sound, and then

being decoded by the listener. Levels of linguistic representation are

constructed during encoding and decoding, but there is no particular association

between the levels of representation used by the speaker and listener.

Thus, there is no reason why those intermediate levels should be retained

(as demonstrated in explicit memory tests with monologue; Jarvella, 1979;

Johnson-Laird & Stevenson, 1970; Sachs, 1967, as well as implicit memory

tests; Garrod & Trabasso, 1973; Garnham, Oakhill, & Cain, 1998).

It is also unclear why alignment should necessarily occur at other levels

of representation beside the situation model.

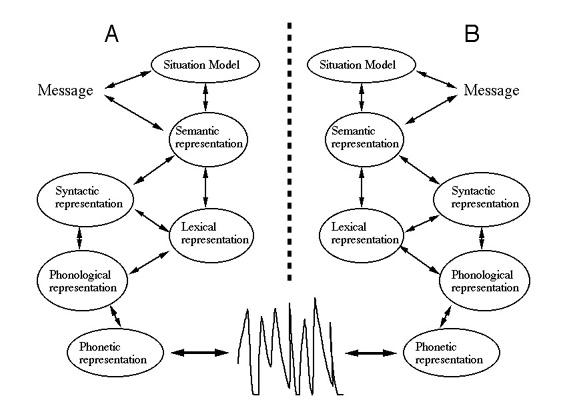

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the stages of comprehension

and production processes according to an autonomous transmission account

of dialogue. The details of the various levels of representation

and interactions between levels are chosen to illustrate the overall architecture

of the system rather than to reflect commitment to a specific model.

Consider, however, what happens in an extended dialogue (see e.g. Clark,

1996; Garrod, 1999). In formulating an utterance the speaker is guided

by what has just been said to her and in comprehending the utterance the

listener is constrained by what he has just said, as in the example dialogue

in Table 1. As the dialogue proceeds, the communicators come to operate

according to the interactive alignment model (see Fig. 3).

This model assumes that interlocutors are continuously aligning their representations

at different linguistic levels. Each level of representation is causally

implicated in the process of communication and these intermediate representations

are retained implicitly. Because alignment at one level leads to alignment

at others, the interlocutors come to align their situation models and hence

are able to understand each other.

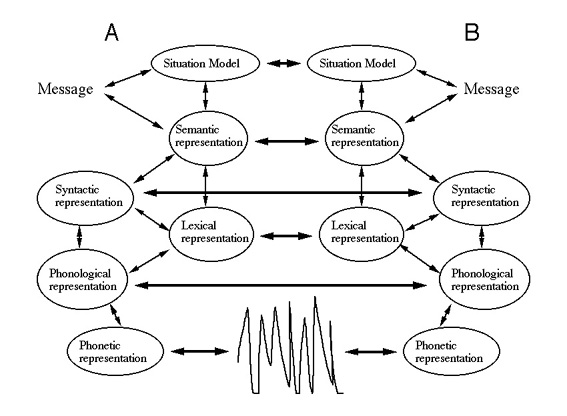

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the stages of comprehension

and production processes according to the interactive alignment account

of dialogue. Again, the details of the representations and interactions

are not meant to reflect particular commitments.

This situation of course only occurs when interlocutors take turns in

contributing — in other words, during dialogue. In monologue (including

writing), the speaker’s and the listener’s representations can rapidly

diverge (or never align at all). The listener then has to draw inferences

on the basis of his knowledge about the speaker, and the speaker has to

infer what the listener has inferred (or simply assume that the listener

has inferred correctly). Of course, either party could easily be wrong,

and these inferences will often be costly. In monologue, the automatic

mechanisms of alignment are not present (the consequences for written production

are demonstrated in Traxler & Gernsbacher, 1992, 1993). It is only

when regular feedback occurs that the interlocutors can control the alignment

process.

3.1 Parity between comprehension and production.

On the autonomous transmission account, the processes employed in production

and comprehension need not draw upon the same representations (see Fig.

2). By contrast, the interactive alignment model assumes that the processor

draws upon the same representations (see Fig. 3). This parity

means that a representation that has just been constructed for the purposes

of comprehension can then be used for production (or vice versa). This

straightforwardly explains, for instance, why we can complete one another’s

utterances (and get the syntax, semantics, and phonology correct; see Section

7.1).

The notion of parity of representation is controversial but has been

advocated by a wide range of researchers working in very different domains

(Calvert et al., 1997; Lahiri & Marslen-Wilson, 1991; Liberman &

Whalen, 2000; MacKay, 1987; Mattingly & Liberman, 1988). It is also

increasingly advocated as a means of explaining perception/action interactions

outside language (Hommel, Müsseler, Aschersleben, & Prinz, in

press). Note that only the representations must be the same. The processes

leading to those representations need not be related (e.g., there is no

need for the mapping between representations to be simply reversed in production

and comprehension).

3.2 Assumptions behind the interactive alignment model

To summarize, the interactive alignment model differs from autonomous

transmission account with respect to three sets of assumptions: (1) There

is priming at different levels of linguistic representation and priming

of the links between the different levels; (2) there is parity between

the representations used for production and comprehension processes, so

representations activated in comprehension will affect production processes

and vice versa; (3) priming is enhanced during dialogue because of the

cumulative and reciprocal nature of the production and comprehension processes.

4. INTERACTIVE ALIGNMENT AND DIALOGUE INFERENCE

Alignment between interlocutors has traditionally been thought to arise

from the establishment of common, mutual, or joint knowledge (Lewis, 1969;

McCarthy, 1990; Schiffer, 1972). An influential example of this approach

is Clark and Marshall’s (1981) argument that successful reference depends

on the speaker and the listener inferring mutual knowledge about the circumstances

surrounding the reference. Thus, for a female speaker to be certain that

a male listener understands what is meant by "the movie at the Roxy," she

needs to know what he knows and what he knows that she knows, and so forth.

Likewise, for him to be certain about what she means by "the movie at the

Roxy," he needs to know what she knows and what she knows that he knows,

and so forth. However, there is no foolproof procedure for establishing

mutual knowledge, because it requires formulating recursive models of interlocutors’

beliefs (see Clark, 1996, chapt. 4; Halpern & Moses, 1990; Lewis, 1969).

Therefore, Clark and Marshall (1981) suggested that interlocutors instead

infer what Stalnaker (1978) called the common ground. This involves what

can reasonably be assumed to be known to both of them on the basis of the

evidence at hand (e.g., if both know that they come from the same city

they can assume a degree of common knowledge about that city; if both admire

the same view and it is apparent to both that they do so, they can infer

a common perspective).

4.1 Limits on common ground inference

To represent common ground directly requires the interlocutor to retain

a very complex model that specifies both her own knowledge and the knowledge

that she assumes to be shared with her partner. To do this, she has to

keep track of the knowledge state of her interlocutor in a way that is

separate from her own knowledge state. This is a very stringent requirement

for routine communication, in part because she has to make sure that this

model is constantly updated appropriately (e.g., Halpern & Moses, 1990).

So it is perhaps not surprising that studies of both production and comprehension

in situations where there is no direct interaction (i.e., situations which

do not allow feedback) indicate that language users do not always take

common ground into account in producing or interpreting references.

For example, Horton and Keysar (1996) found that speakers under time

pressure did not produce descriptions that took advantage of what they

knew about the listener’s view of the relevant scene. In other words, the

descriptions were formulated with respect to the speaker’s current knowledge

of the scene rather than with respect to the speaker and listener’s common

ground. Keysar, Barr, Balin, and Paek (1998) found that in visually searching

for a referent for a description listeners are just as likely to initially

look at things that are not part of the common ground as things that are.

In a similar vein, Brown and Dell (1987) showed that apparent listener-directed

ellipsis was not modulated by information about the common ground between

speaker and listener, but rather was determined by the accessibility of

the information for the speaker alone (but see Schober & Brennan, 2001,

for reservations).

Even in fully interactive dialogue it is difficult to find evidence

for direct listener modeling. For example, it was originally thought that

articulation reduction might reflect the speaker’s sensitivity to the listener’s

current knowledge (Lindblom, 1990). However, Bard et al. (2000) found that

the same level of articulation reduction occurred even after the speaker

encountered a new interlocutor. In other words, degree of reduction seemed

to be based only on whether the reference was given information for the

speaker and not on whether it was part of the common ground. Additionally,

speakers will sometimes use definite descriptions (to mark the referent

as given information; Haviland & Clark, 1974) when the referent is

visible to them, even when they know it is not available to their interlocutor

(Anderson & Boyle, 1994).

Nevertheless, under certain circumstances interlocutors do engage in

strategic inference relating to common ground. As Horton and Keysar (1996)

found, with less time pressure speakers often do take account of common

ground in formulating their utterances, and as Keysar et al. (1998) argued

in their perspective adjustment model, listeners can at a later monitoring

stage take account of common ground in comprehension under circumstances

in which speaker/listener perspectives are radically different (see also

Brennan & Clark, 1996; Schober & Brennan, 2001).

Taken together, these results suggest that performing inferences about

common ground is an optional strategy that interlocutors employ only when

resources allow (see Clark & Wasow, 1998, p 202 and section 4.2). Critically,

such strategies need not always be used, and most "simple" (e.g., dyadic,

non-didactic, non-deceptive) conversation works without them most of the

time.

4.1.1 Interactive alignment produces an implicit common ground

In Section 2 we argued that dialogue participants automatically build

up aligned representations, including aligned situation models. Whereas

Clark and Marshall (1981) argued that interlocutors need to infer common

ground explicitly, we argue that this is not necessary because the shared

information in the aligned representations already constitutes an implicit

common ground. We call it implicit common ground because it reflects information

that is in both interlocutors’ situation models, but does not derive from

communicators explicitly modelling their partner’s beliefs.

Of course, the process of alignment does not always lead to appropriately

aligned representations. Under these circumstances the implicit common

ground is faulty because it does not reflect shared knowledge (i.e., knowledge

that they both actually have irrespective of whether each knows the other

has it). So how can the interlocutors rectify the situation? We argue that

they employ an interactive inference mechanism to ensure that the implicit

common ground truly reflects shared knowledge. The mechanism relies on

two processes: (1) monitoring the input in relation to one’s own representation,

and (2) an interactive repair process aimed at re-establishing alignment

under circumstances where utterances cannot be resolved against this representation.

Consider again the example in Table 1. Throughout this section of dialogue

A

and B assume subtly different interpretations for two along.

A

interprets

two along by counting the boxes on the maze, whereas

B

is counting the links between the boxes (see Fig. 1). This temporary

misalignment arises because the two speakers represent the meaning of expressions

like

two along differently in this context.

Therefore, the players engage in an interactive repair process. If the

input that they receive cannot be resolved in relation to their current

representation, then they reformulate the information at their next turn.

The reformulation can be a simple repetition with rising intonation (as

in 7), a repetition with an additional query (as in 5), or a more radical

restatement (as when A reformulates "two along" as "second box"

in 6). Such reformulation throws the problem back to the interlocutor,

and the cycle continues until the misalignment has been resolved (for discussion

of such embedded repairs see Jefferson, 1987). In fact, the misalignment

is only satisfactorily resolved at a much later point (43-44) when A

is able to complete B’s utterance without further challenge.

This account is consistent with the findings that speakers regularly

adapt their utterances according to whether the information can be accessed

within their own situational model rather than via a direct assessment

of common ground. However, because access is from aligned representations

which reflect the implicit common ground these adaptations will normally

be helpful incidentally for the listener (for further discussion see Brown

& Dell, 1987). For example, when speakers reduce the articulation of

easily accessible repeated expressions, those expressions tend to be more

recognisable to the listener as well (Bard et al., 2000), as most of the

time the listener has heard the earlier uses of the expression. Whereas

in the autonomous transmission account discourse inference processes are

internalised in the minds of the speaker and listener, in the interactive

alignment account the process can be externalised in the interchange between

the two dialogue participants supported by the process of aligning output

and input.

4.2 Interactive alignment and more complicated inference strategies

The interactive inference mechanism is basic because it only relies

on the speaker monitoring the conversation in relation to her own knowledge

of the situation. Of course there will be occasions when a more complicated

and strategic assessment of common ground may be necessary, most obviously

when interlocutors are not well aligned in some critical respect. In such

cases, the listener may have to draw inferences about the speaker (e.g.,

"She has referred to John; does she mean John Smith or John Brown? She

knows both, but thinks I don’t know Brown, hence she probably means Smith.").

Other important cases are when one speaker is trying to deceive the other

in some way or to conceal information (e.g., Clark & Schaefer, 1987),

or when people decide deliberately not to align at some level (e.g., by

refusing to use the same expression as one’s interlocutor because it has

a political implication that one finds distasteful; Jefferson, 1987). Such

cases may involve complex (and probably conscious) reasoning, and there

may be great differences between people’s abilities (e.g., between those

with and without an adequate "theory of mind"; Baron-Cohen, Tager-Flusberg,

& Cohen, 2000). For example, Garrod and Clark (1993) found that younger

children could not circumvent the automatic alignment process. Seven year

old maze-game players failed to introduce new description schemes when

they should have done so, because they could not overcome the pressure

to align their description with the previous one from the interlocutor.

By contrast, older children and adults were twice as likely to introduce

a new description scheme when they had been unable to understand their

partner’s previous description. Whereas the older children could adopt

a strategy of non-alignment when appropriate, the younger children seemed

unable to do so. Our claim is that these strategic processes are overlaid

on the basic interactive alignment mechanism. However, such strategies

are clearly costly in terms of processing resources and may be beyond the

abilities of less skilled language users.

The strategies discussed above relate specifically to alignment (either

avoiding it or achieving it explicitly), but of course many aspects of

dialogue serve far more complicated functions. Thus, a speaker can attempt

to produce a particular emotional reaction in the listener by an utterance,

or persuade the listener to act in a particular way or to think in depth

about an issue (e.g., in expert-novice interactions; see Isaacs & Clark,

1987). Likewise, the speaker can draw complex inferences about the mental

state of the listener and can try to probe this state by interrogation.

Thus, it is important to stress that we are proposing interactive alignment

as the primitive mechanism underlying dialogue, not a replacement for the

more complicated strategies that conversationalists may employ on occasion.

However, we claim that normal conversation does not routinely require

modeling the interlocutor’s mind. Instead, the overlap between interlocutors’

representations is sufficiently great that a specific contribution by the

speaker will either trigger appropriate changes in the listener’s representation,

or will bring about the process of interactive repair. Hence, the listener

will retain an appropriate model of the speaker’s mind, because, in

all essential respects, it is the listener’s representation as well.

Processing monologue is quite different in this respect. Without automatic

alignment and interactive repair the listener can only resort to costly

bridging inferences whenever she fails to understand anything. And, to

ensure success, the speaker will have to design what he says according

to what he knows about the audience (see Clark & Murphy, 1982). In

other words, he will have to model the audience’s state of knowledge.

5. ALIGNMENT AND ROUTINIZATION

The process of alignment means that interlocutors draw upon representations

that have been developed during the dialogue. Thus it is not always necessary

to construct representations that are used in production or comprehension

from scratch. This perspective radically changes our accounts of language

processing in dialogue. One particularly important implication is that

interlocutors develop and use routines (set expressions) during a particular

interaction. Most of this section addresses the implications of this perspective

for language production, where they are perhaps most profound. We then

turn more briefly to language comprehension.

5.1 Speaking: Not necessarily from intention to articulation.

The seminal account of language production is Levelt's (1989) book Speaking,

which has the informative subtitle From intention to articulation.

Chapter by chapter, Levelt describes the stages involved in the process

of language production, starting with the conceptualization of the message,

through the process of formulating the utterance as a series of linguistic

representations (representing grammatical functions, syntactic structure,

phonology, metrical structure, etc.), through to articulation. The core

assumption is that the speaker necessarily goes through all of these stages

in a fixed order. The same assumption is common to more specific models

of word production (e.g., Levelt et al., 1999) and sentence production

(e.g., Bock & Levelt, 1994; Garrett, 1980). Experimental research is

used to back up this assumption. In most experiments concerned with understanding

the mechanisms underlying language production, the speaker is required

to construct the word or utterance from scratch, or from a pre-linguistic

level at least. For example, a common method is picture description (e.g.,

Bock, 1986b; Schriefers, Meyer, & Levelt, 1990). These experiments

therefore employ methods that reinforce the ideomotor tradition of action

research that underlies Levelt’s framework (see Hommel et al., in press).

It appears to be universally agreed that this exhaustive process is

logically necessary because speakers have to articulate the words. Indeed,

a common claim in work on language production is that, while comprehenders

can sometimes "short-circuit" the comprehension process by taking into

account the prior context (e.g., guessing thematic roles without actually

parsing), producers always have to go through each step from beginning

to end. To quote Bock and Huitema (1999 p.385):

"… there may be times when just knowing the words in their contexts

is enough to understand the speaker, without a complete syntactic analysis

of the sentence. But in producing a sentence, a speaker necessarily assigns

syntactic functions to every element of the sentence; it is only by deciding

which phrase will be the subject, which the direct object, and so on that

a grammatical utterance can be formed — there is no way around syntactic

processing for the speaker."

In fact, this assumption is wrong: It is logically just as possible to

avoid levels of representation in production as in comprehension. Although

we know that a complete output normally occurs in production, we do not

know what has gone on at earlier stages. Thus, it is entirely possible,

for example, that people do not always retrieve each lexical item as a

result of converting an internally generated message into linguistic form

(as assumed by Levelt et al, 1999, for example), but rather that people

draw upon representations that have been largely or entirely formed already.

Likewise, sentence production need not go through all the representational

stages assumed by Garrett (1980), Bock and Levelt (1994), and others. For

instance, if one speaker simply repeated the previous speaker’s utterance,

the representation might be taken "as a whole," without lexical access,

formulation of the message, or computation of syntactic relations.

Repetition of an utterance may seem unnatural or uncertainly related

to normal processing, but in fact, as we have noted, normal dialogue is

highly

repetitive (e.g., Tannen, 1989). This is of course different from carefully

crafted monologue where — depending to some extent on the genre — repetition

is regarded as an indication of poor style (see Amis, 1997, pp. 246-250).

In our example dialogue 82% of the 127 words are repetitions; in this paragraph

only 25% of the 125 words are repetitions. (Ironically, we — the authors

— have avoided repetition even when writing about it.) In fact, the assumption

that repetition is unusual or special is a bias probably engendered by

psychologists’ tendency to spend much of their time reading formal prose

and designing experiments using decontextualized "laboratory" paradigms

like picture naming.

So it is possible that people can short-circuit parts of the production

process just as they may be able to short-circuit comprehension. Moreover,

this may be a normal process that occurs when engaged in dialogue. We strongly

suspect (see below) that phrases (for instance) are not simply inserted

as a whole, but that the true picture is rather more complicated. But it

is critical to make the logical point that the stages of production are

not set in stone, as previous theories have assumed.

5.2 The production of routines

A routine is an expression that is "fixed" to a relatively great

extent. First, the expression has a much higher frequency than the frequency

of its component words would lead us to expect (e.g., Aijmer, 1996).

(In computational linguistics this corresponds to having what is called

a high "mutual information" content; Charniak, 1993.) Second, it has a

particular analysis at each level of linguistic representation. Thus, it

has a particular meaning, a particular syntactic analysis, a particular

pragmatic use, and often particular phonological characteristics (e.g.,

a fixed intonation). Extreme examples of routines include repetitive conversational

patterns such as How do you do? and Thank you very much.

Routines are highly frequent in dialogue: Aijmer estimates that up to 70%

of words in the London-Lund speech corpus occur as part of recurrent word

combinations (see Altenberg, 1990). However, different expressions can

be routines to different degrees, so actual estimates of their frequency

are somewhat arbitrary. Some routines are idioms, but not all (e.g., I

love you is a routine with a literal interpretation in the best relationships;

see Nunberg, Sag, & Wasow, 1994; Wray & Perkins, 2001)

Most discussion of routines focuses on phrases whose status as a routine

is pretty stable. Although long-term routines are important, we also claim

that routines are set up "on the fly" during dialogue. In other words,

if an interlocutor uses an expression in a particular way, it may become

a routine for the purposes of that conversation alone. We call this process

routinization.

Here we consider why routines emerge and why they are useful. The next

section considers how they are produced (in contrast to non-routines).

This, we argue, leads to a need for a radical reformulation of accounts

of sentence production. Finally, we consider how the comprehension of routines

causes us to reformulate accounts of comprehension.

5.2.1 Why do routines occur?

Most stretches of dialogue are about restricted topics and therefore

have quite a limited vocabulary. Hence, it is not surprising that routinization

occurs in dialogue. But monologue can also be about restricted topics,

and yet all indications suggest it is much less repetitive and routinization

is much less common. The more interesting explanation for routinization

in dialogue is that it is due to interactive alignment. A repeated expression

(with the same analysis and interpretation) is of course aligned at most

linguistic levels. Thus, if interlocutors share highly activated semantic

representations (what they want to talk about), lexical representations

(what lexical items are activated), and syntactic representations (what

constructions are highlighted), they are likely to use the same expressions,

in the same way, to refer to the same things. The contrast with most types

of monologue occurs (in part, at least) because the producer of a monologue

has no-one to align her representations with (see Section 2). The use of

routines contributes enormously to the fluency of dialogue in comparison

to most monologue — interlocutors have a smaller space of alternatives

to consider and have ready access to particular words, grammatical constructions,

and concepts.

Consider the production of expressions that keep being repeated in a

dialogue, such as "the previous administration" in a political discussion.

When first used, this expression is presumably constructed by accessing

the meaning of "previous" and combining it with the meaning of "administration."

The speaker may well have decided "I want to refer to the Conservative

Government, but want to stress that they are no longer in charge, etc.

so I’ll use a circumlocution." He will construct this expression by selecting

the words and the construction carefully. Likewise, the listener will analyze

the expression and consider alternative interpretations. Both interlocutors

are therefore making important choices about alternative forms and interpretations.

But if the expression is repeatedly used, the interlocutors do not have

to consider alternatives to the same extent. For example, they do not have

to consider that the expression might have other interpretations, or that

"administration" is ambiguous (e.g., it could refer to a type of work).

Instead, they treat the expression as a kind of name that refers to the

last Conservative government. Similar processes presumably occur when producing

expressions that are already frozen (Pinker & Birdsong, 1979; see also

Aijmer, 1996). Generally, the argument is that people can "shortcircuit"

production in dialogue, by removing or drastically reducing the choices

that otherwise occur during production (e.g., deciding which synonym to

use, or whether to use an active or a passive).

Why might this happen? The obvious explanation is that routines are

in general easier to produce than non-routines. Experimental work on this

is lacking, but an elegant series of field studies by Kuiper (1996) suggest

that this explanation is correct. He investigated the language of sports

commentators and auctioneers, who are required to speak extremely quickly

and fluently. For example, radio horse-racing commentators have to produce

a time-locked and accurate monologue in response to rapidly changing events.

This monologue is highly repetitive and stylized, but quite remarkably

fluent. He argued that the commentators achieve this by storing routines,

which can consist of entirely fixed expressions (e.g., They are coming

round the bend) or expressions with an empty slot that has to be filled

(e.g., X is in the lead), in long-term memory, and then access these

routines, as a whole, when needed. Processing load is thereby greatly reduced

in comparison to non-routine production. Of course, this reduction in load

is only possible because particular routines are stored; and these routines

are stored because the commentators repeatedly produce the same small set

of expressions in their career.

Below, we challenge his assumption that routines are accessed "as a

whole," and argue instead that some linguistic processing is involved.

But we propose a weaker version of his claims, namely that routines are

accessed telegraphically, in a way that is very different from standard

assumptions about language production (as in, e.g., Levelt, 1989). Moreover,

we argue that not all routines are learned over a long period, but that

they can instead emerge "on the fly," as an effect of alignment during

dialogue.

5.2.2 Massive priming in language production

Contrary to Kuiper (1996), some compositional processes take place in

routines, as we know from the production of idiom blends (e.g., That’s

the way the cookie bounces) (Cutting & Bock, 1997). However, there

are good reasons to assume that production of idioms and other routines

may be highly telegraphic. The normal process of constructing complex expressions

involves a large number of lexical, syntactic, and semantic choices (why

choose one word or form rather than another, for instance). In contrast,

when a routine is used, most of these choices are not necessary. For example,

speakers do not consider the possibility of passivizing an idiom that is

normally active (e.g., The bucket was kicked), so there is no stage

of selection between active and passive. Likewise, they do not consider

replacing a word with a synonym (e.g., kick the pail), as the meaning

would not be preserved. Similarly, a speech act like I name this ship

X is fixed, insofar as particular illocutionary force depends on the

exact form of words (cf. I give this ship the name X). Also, flat

intonation suggests that no choices are made about stress placement (Kuiper,

1996).

Let us expand this by extending some of the work of Potter and Lombardi

to dialogue (Lombardi & Potter, 1992; Potter & Lombardi, 1990,

1998). They address the question of how people recall sentences (see also

Bock, 1986b, 1996). Recall differs from dialogue in that (1) the same sentences

are perceived and produced; and (2) there is only one participant, acting

as both comprehender and producer. Potter and Lombardi had experimental

subjects read and then recall sentences whilst performing concurrent tasks.

They found that a "lure" word sometimes intruded into the recalled sentence,

indicating that subjects did not always store the surface form of the sentence;

that these lure words caused the surface syntax of the sentence to change

if they intruded and did not fit with the sentence that was read; and that

other clauses could syntactically prime the target sentence so that it

was sometimes misremembered as having the form of the prime sentence. They

argued that people did not remember the surface form of the sentence but

rather remembered its meaning and had the lexical items and syntactic constructions

primed during encoding. Recall therefore involved converting the meaning

into the surface form using the activation of lexical items and syntax

to cause a particular form to be regenerated. In normal sentence recall,

this is likely to be the form of the original sentence.

This suggests that language production can be greatly enhanced by the

prior activation of relevant linguistic representations (in this case,

lexical and syntactic representations). In dialogue, speakers do not normally

aim simply to repeat their interlocutors’ utterances. However, production

will be greatly enhanced by the fact that previous utterances will activate

their syntactic and lexical representations. Hence, they will tend to repeat

syntactic and lexical forms, and therefore to align with their interlocutors.

These arguments suggest why sentence recall might actually present a reasonable

analogue to production in naturalistic dialogue; and why it is probably

a better analogue than, for instance, isolated picture description. In

both sentence recall and production in dialogue, very much less choice

needs to be made than in monologue. The decisions that occur in language

production (e.g., choice of word or structure) are to a considerable extent

driven by the context and do not need to be a burden for the speaker. Thus,

they are at least partly stimulus-driven rather than entirely internally

generated, in contrast to ideomotor accounts like Levelt (1989).

However, our account differs from Potter and Lombardi’s in one respect.

They assume no particular links between the activation of syntactic information,

lexical information, and the message. In other words, the reason that we

tend to repeat accurately is that the appropriate message is activated,

the appropriate words are, and the appropriate syntax is. But we have already

argued that alignment at one level leads to more alignment at other levels

(e.g., syntactic priming is enhanced by lexical overlap; Branigan et al.,

2000), and that this is due to Hebbian learning. The alignment model assumes

interrelations between all levels, so that a meaning, for instance, is

activated at the same time as a word. This explains why people not only

repeat words but also repeat their senses in a dialogue (Garrod & Anderson,

1987). In other words, what actually occurs in dialogue is lots of lexical,

syntactic, and semantic activation of various tokens at each level, and

activation of particular links between the levels. This leads to a great

deal of alignment, and hence the production of routines. It also means

that the production of a word or utterance in dialogue is only distantly

related to the production of a word or utterance in isolation.

Kuiper (1996) assumes that most routines are stored after repeated use,

in a way that is not directly related to dialogue. However, he considers

an example of how an auctioneer creates a "temporary formula" by repeating

a phrase (p. 62). He regards this case as exceptional and does not employ

it as part of his general argument. In contrast, we assume that the construction

of temporary formulae is the norm in dialogue. Many studies show how new

descriptions become established for the dialogue (e.g., Brennan & Clark,

1996; Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986; Garrod & Anderson, 1987). In

general it is striking how quickly a novel expression can be regarded as

entirely normal, whether it is a genuine neologism or a novel way of referring

to an object (Gerrig & Bortfeld, 1999).

In situations in which a community of speakers regularly discuss the

same topic we might expect the transient routines that they establish to

eventually become fixed within that community. In fact, Garrod and Doherty

(1994) demonstrated that an experimentally established community of maze-game

players quickly converged on a common description scheme. They also found

that the scheme established by the community of players was used more consistently

than schemes adopted by isolated pairs of players over the same period.

This result points to the interesting possibility that the interactive

alignment process can be responsible for fixing routines in the language

or dialect spoken by a community of speakers (see Clark, 1998).

5.2.3 Producing words and sentences

Most models of word production assume that the apparent fluency of production

hides a number of stages that lead from conceptual activation to articulation.

In Levelt et al. (1999) a lexical entry consists of sets of nodes at different

levels (or strata): a semantic representation, a syntactic (or lemma) representation,

a phonological representation, a phonetic representation, and so on. Each

level is connected to the one after it, so that the activation of a semantic

representation (e.g., for cat) leads to the activation of its syntactic

representation (the "cat" lemma plus syntactic information specifying that

it is a singular count noun), which in turn leads to the access of the

phonological representation /k//a//t/. Evidence for the sequential nature

of activation comes from time-course data (Schriefers et al., 1990; van

Turrennout, Hagoort, & Brown, 1998), "tip-of-the-tongue" data (Vigliocco,

Antonini, & Garrett, 1997), and so on. Alternative accounts question

the specific levels assumed by Levelt et al. and the mechanisms of activation

but do not question the assumption that earlier levels become activated

before later ones (Caramazza, 1997; Dell, 1986). Notice that the data used

to derive these accounts is almost entirely based on paradigms that require

generation from scratch (e.g., picture naming) or from linguistic information

with a very indirect relationship to the actual act of production required

(e.g., responding with the object of a definition).

We do not contend that the dialogical perspective leads us to a radically

different view of word production. More specifically, we have no reason

to doubt that the same levels of representation are accessed in the same

order during production in dialogue (though this question has not been

addressed by mainstream psycholinguistic research). For example, Potter

and Lombardi’s data suggest that even in repetition of a word, it is likely

that lexical access occurs (and that there is no direct access of the word-form,

for example). However, contextual activation is likely to have some effects

on the time-course of production, particularly in relation to the decisions

at different stages in the production process. For example, a choice between

two synonyms might normally involve some processing difficulty, but if

one has been established in the dialogue (e.g., by lexical entrainment),

no meaningful process of selection is needed.

The situation is very different with isolated sentence production. Models

of production assume that a speaker initially constructs a message, then

converts this message into a syntactic representation, then into a phonological

representation, and then into sound (Bock & Levelt, 1994; Garrett,

1980; Levelt, 1989). Normally, they also assume that the syntactic level

involves at least two stages: a functional representation, and a constituent-structure

representation. It is accepted that cascading may happen, so that the complete

message does not need to be computed before syntactic encoding can begin

(e.g., Meyer, 1996). But ordering is assumed, so that, for instance, a

word cannot be uttered until it is assigned a functional role and a position

within a syntactic representation.

However, we propose that it may be possible to break this rigid order

of sentence production, and instead to build a sentence "around" a particular

phrase if that phrase has been focused in the dialogue. In accord with

this, context can affect sentence formulation in monologue, so that a focused

phrase is produced first (Bock, 1986a; Prat-Sala & Branigan, 2000).

Prat-Sala and Branigan, in particular, found effects of focus on word order

that were not due to differences in grammatical function. Hence it may

be possible to utter a phrase before assigning it a grammatical function.

For instance, in That picture, I think you like, and That picture,

I think pleases you, the meaning of That picture does not vary

but its grammatical function (subject or object) does vary. Assuming that

production is at least partially incremental, people can therefore utter

That

picture before assigning it a grammatical function. This would of course

not be possible within traditional models where phonological representations

and acoustic form cannot be constructed before grammatical function is

assigned (e.g., Bock & Levelt, 1994). So the effects of strong context,

in either dialogue or monologue, may be to change the process of sentence

production quite radically.

5.3 Alignment in comprehension

The vast literature on lexical comprehension is almost entirely concerned

with monologue (e.g., reading words in sentential or discourse contexts)

or isolated words. But the alignment model suggests that lexical comprehension

in dialogue is very different from monologue. A major consequence of alignment

at a lexical level is that local context becomes central. Listeners, just

like speakers, should be able to select words from a set that have been

central to that dialogue — a "dialogue lexicon."

One of the most universally accepted phenomena in experimental psychology,

enshrined in all classic models (e.g., Morton, 1969), is the word frequency