Where your group creates its page(s)

Wiki

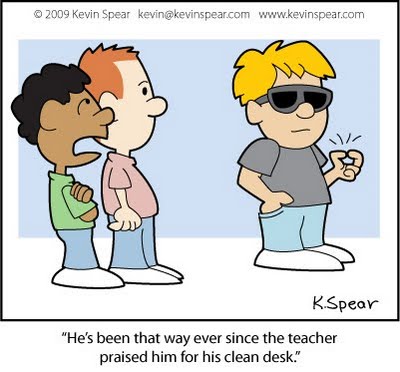

Unconditional praise: a precondition for success or failure?

The connection between false praise, self-esteem and resilience

In order to succeed, people need a sense of self-efficacy, to struggle together with resilience to meet the inevitable obstacles and inequities of life. - Albert Bandura

Introduction

The traditional view of praising children entails the idea that all praise is good praise, however some psychological researchers oppose this notion and instead argue that this may not necessarily be the case.

Praise can be understood as giving positive feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2001), with the view that praising your child will result in increased self-esteem and hence better achievement, e.g. in academia. The concept of false praise, however, defines a situation where one is praised unnecessarily and in undeserving circumstances. This unconditional praise is thought to have negative consequences in the long run, with claims such as increased narcissism, less resilience and distorted self-esteem. It is argued that the individual cannot perceive the true picture of reality, and so fails to differentiate between what is true achievement and what is completion of a meaningless task; hence, they do not form the basis of drive or need for improvement.

The idea of unconditional/false praise is also argued to have a knock on effect on the individual's self-esteem. Self-esteem can be thought of as how much value an individual places on themselves, which can vary on a continuum from low to high (Baumeister et al., 2003). In the context, self-esteem can be reduced due to the idea that a child may attribute negative feelings of achievement directly to them-self, because they have been brought up to believe that achievement is a direct consequence of their abilities, i.e. a constant that cannot change. A direct example of this type of situation is when parents' praise their children for being smart whenever they do well in an exam, oppose to the arguably more efficient technique of praising the effort put in to a task. If the child then poorly performs they are likely to accredit the blame as a reflection of themselves rather than to external factors that can be improved, thus reducing resilience.

Contents

- History and roots in psychology

- Praise, self esteem and resilience - theory and practice

- Clinical applications

- Practical exercises

- Uncritical claims

- Cultural connections

- Further information - articles, podcasts and videos

- Academic references

1. History and roots in psychology

The practice of praising someone for their behaviour has already been present as a central part of modern Christianity: the bible contains hymns of praise as well as the Lord’s Prayer.

According to Wierzbicka (2004) some expressions related to praise such as “good boy” and “good girl” have been found in English literature and language since the mid-1800s. Praise in this way occurs to be a deeply rooted and religiously inspired Anglo-American cultural tradition having its origin in Puritan times where the naughtiness of children has been linked to hellfire. A contrasting positive way of thinking began in the 19thcentury, followed by boosts of self-esteem in the 20th century. Branden (1969) was one of the first to point out the effect of praise on enhancing self-esteem in his book "The Psychology of Self-esteem".

Relating to further scientific evidence, about 40 years ago a growing body of research arose from the early childhood special needs in psychology and education; this postulated the prominent view of praise as a useful tool to enhance motivation and therefore improve behaviour in children. Studies such as those conducted by Zimmerman and Zimmerman (1962), Becker, Madsen, Arnold,and Thomas (1967), and Madsen, Becker, and Thomas (1968) provided evidence for the effectiveness of using praise in reducing inappropriate behaviours, increasing appropriate behaviours, and increasing specific cognitive and motor abilities related to academic or functional tasks.

In contrast, beginning in the 1990s, research such as that conducted by Baumeister (1990) and Mueller and Dweck (1998) started to challenge this common sense view, and postulated that praise has negative effects on children’s learning and motivation. This has been expressed, for example, by Kohn (1993) who said that “the most notable aspect of a positive judgment is not that it is positive but that it is a judgment” (p. 102).

2. Praise, self-esteem and resilience – theory and practice

“Everybody has won and all must have prizes” Lewis Caroll, 1865

A 2007 report by UNICEF on child well-being in rich countries indicated that the UK came bottom out of 27 countries with the US being second from the bottom. If this measure is taken to include self-esteem, then clearly there has been no beneficial effect of praise over the previous three decades.

Carol Dweck’s programme of research on intelligence suggests that praise is connected to how student view their intelligence. If students believe that there is no way of changing their intelligence, a fixed mindset, then this will impact on their motivation to learn and improve. Alternatively, if students believe that their intelligence can increase based on the amount of effort that they make, a growth mindset, then they will focus on achieving goals (Dweck, 2008; Mueller & Dweck, 1998). The use of false praise is therefore connected to reinforcing a fixed mindset, if children are told they are intelligent ("gee, you're smart") rather than praised for their effort ("wow, you worked really hard"). Dweck's theory is encompassed in her model of incremental intelligence.

Carol Dweck’s programme of research on intelligence suggests that praise is connected to how student view their intelligence. If students believe that there is no way of changing their intelligence, a fixed mindset, then this will impact on their motivation to learn and improve. Alternatively, if students believe that their intelligence can increase based on the amount of effort that they make, a growth mindset, then they will focus on achieving goals (Dweck, 2008; Mueller & Dweck, 1998). The use of false praise is therefore connected to reinforcing a fixed mindset, if children are told they are intelligent ("gee, you're smart") rather than praised for their effort ("wow, you worked really hard"). Dweck's theory is encompassed in her model of incremental intelligence.

A review of the self-esteem literature by Baumeister et al. (2003) did not find any evidence that interventions aimed at increasing self-esteem gave benefits. In addition, they viewed that due to the variety of ways in which self-esteem can present, indiscriminate praise may produce narcissism. They concluded that praise should be used as a reward for specific actions.

Not all studies support Dweck's model of incremental intelligence. In a two year longitudinal study at University College London, Furnham et al. (2003) found no relationship between academic performance and beliefs in intelligence in students. Niiya et al. (2010) found that personality was more of a predictor of academic performance that belief in intelligence, specifically levels of conscientiousness.

The idea of a growth mindset could also be seen to go against another one of positive psycholoygy’s own ideas, that of using signature strengths. The strengths approach has individuals identify what they are good at using a questionnaire and then use these strengths in their everyday life. This focuses on what someone can currently do rather than developing new skills. However the two processes, using strengths on one hand and having a growth mindset on the other could be seen as having different possible outcomes, with the use of strengths improving feelings of happiness and growth mindset increasing resilience and self-efficacy. Thus the debate in this area is still ongoing.

The growth in positive psychology, including research on false praise, resilience and self-esteem has given rise to a number of interventions that can be used in clinical settings.

This emphasises the view that psychology should have alternative options rather than just relieving human suffering, but to also include human flourishing.

3. Clinical applications

There are various possible clinical applications that make it important for the debate about false praise, self-esteem and resilience to be continued. If it is true that praise might in fact have negative consequences in certain circumstances, these results must be applied in clinical practice. There are a number of studies that have tried to investigate this topic within a clinical setting.

Kruger and Dunning (1999) have found that people who have difficulties in recognizing their inabilities in certain tasks, will overestimate their skill in this task. Moreover, they have shown that people will recognize their limitations when skill is improved. Thinking further, one might suggest that false praise might lead to an unjustified feeling of self-esteem that would in fact not be helpful in everyday situations, as someone might not try and improve their skill after unjustified praise. This argument is supported by the fact that participants in a study who had been given accurate feedback realized their weaknesses and recognized their need to improve performance (Kim & Chiu, 2011). These results have to be considerd in any clinical setting, as they show how, for example psychotherapists have to carefully consider the circumstances when giving praise.

Forte, Jahoda and Dagnan (2011) have explored how young people with a mild intellectual ability compared to young people without disabilities cope with their worries. They come to the conclusion that promoting resilience in young people with a mild disability can help to decrease their worries which were also linked to low self-esteem. In this case, the approach of promoting resilience can be used for young people with mild disabilities in order to facilitate the transition to adulthood and to strengthen their self-esteem. What other clinical applications can be thought of?

It has been found that people with low self-esteem are at higher risk of developing subsequent depression when a major stressor occurs (Brown, Andrews, Harris, Adler, & Bridge, 1986). Furthermore, Dumont and Provost (1999) have shown that vulnerable adolescents with higher depression scores had lower self-esteem than resilient adolescents. Therefore, it can be argued that resilience training and raising self-esteem can be valuable in the prevention and treatment of depression. This makes it an important goal to understand the connection between praise, self-esteem and resilience.

One can certainly argue that the consequences of praise will be moderated by the characteristics of the recipient, such as gender, age or culture (Henderlong & Lepper, 2002). These characteristics have to be taking into consideration in the various clinical settings. Furthermore, taking a focus of promoting resilience and increasing self-esteem, instead of unconditional praise seems to be the best approach to achieve success in clinical practice. In the next paragraph practical exercises to promote resilience will show how the clinical findings can be employed in practice in order to facilitate an active move towards change.

4.1 Practical Exercises: Suggestions for improving resilience

1. Make connections. Good relationships with close family members, friends, or others are important. Accepting help and support from those who care about you and will listen to you strengthens resilience. Some people find that being active in civic groups, faith-based organizations, or other local groups provides social support and can help with reclaiming hope. Assisting others in their time of need also can benefit the helper.

2. Avoid seeing crises as insurmountable problems. You can't change the fact that highly stressful events happen, but you can change how you interpret and respond to these events. Try looking beyond the present to how future circumstances may be a little better. Note any subtle ways in which you might already feel somewhat better as you deal with difficult situations.

3. Accept that change is a part of living. Certain goals may no longer be attainable as a result of adverse situations. Accepting circumstances that cannot be changed can help you focus on circumstances that you can alter.

4. Move toward your goals. Develop some realistic goals. Do something regularly -- even if it seems like a small accomplishment that enables you to move toward your goals. Instead of focusing on tasks that seem unachievable, ask yourself, "What's one thing I know I can accomplish today that helps me move in the direction I want to go?"

5. Take decisive actions. Act on adverse situations as much as you can. Take decisive actions, rather than detaching completely from problems and stresses and wishing they would just go away.

6. Look for opportunities for self-discovery. People often learn something about themselves and may find that they have grown in some respect as a result of their struggle with loss. Many people who have experienced tragedies and hardship have reported better relationships, greater sense of strength even while feeling vulnerable, increased sense of self-worth, a more developed spirituality, and heightened appreciation for life.

7. Nurture a positive view of yourself. Developing confidence in your ability to solve problems and trusting your instincts helps build resilience.

8. Keep things in perspective. Even when facing very painful events, try to consider the stressful situation in a broader context and keep a long-term perspective. Avoid blowing the event out of proportion.

9. Maintain a hopeful outlook. An optimistic outlook enables you to expect that good things will happen in your life. Try visualizing what you want, rather than worrying about what you fear.

10. Take care of yourself. Pay attention to your own needs and feelings. Engage in activities that you enjoy and find relaxing. Exercise regularly. Taking care of yourself helps to keep your mind and body primed to deal with situations that require resilience.

Additional ways of strengthening resilience may be helpful. For example, some people write about their deepest thoughts and feelings related to trauma or other stressful events in their life. Meditation and spiritual practices help some people build connections and restore hope.

The above ideas are fairly general giving each individual the opportunity to tailor these to work with their own lifestyle.

4.2 How to give good praise!

1. Be specific. Praise needs to be directed at something in particular rather than general, and also needs to be about what the person can control - otherwise it may just sound empty.

1. Be specific. Praise needs to be directed at something in particular rather than general, and also needs to be about what the person can control - otherwise it may just sound empty.

2. Acknowledge the actor. Rather than just saying 'well that turned out well' make sure the person involved gets the credit.

3. The effusiveness and time spent in giving praise should be commensurate with the difficulty and time-intensiveness of the task. If a task was quick and easy, a hasty “Looks great!” will do; if a task was protracted and difficult, the praise should be more lengthy and descriptive. Also, you might bring up the praise more than once.

4. Remember the negativity bias. The “negativity bias” is a well-recognized psychological phenomenon: people react to the bad more strongly and persistently than to the comparable good. So if you want to praise someone, remember that one critical comment will wipe out several positive comments, and will be far more memorable. To stay silent, and then remark something like, “It’s too bad that that door couldn’t be fixed,” will be perceived as highly critical.

5. Praise the everyday as well as the exceptional. When people do something unusual, it’s easy to remember to give praise. But what about the things they do well every day without any recognition? It never hurts to point out how much you appreciate the small services and tasks that someone unfailingly performs. Something like, “You know what? In three years, I don’t think you’ve ever been even an hour late with the weekly report.” After all, we never forget to make a comment when someone screws up.

5. Uncritical Claims

In all studies considered, there seemed to be a lack of a specific and consistent measure for praise. This, hence, makes it extremely difficult to draw conclusions and make such claims in relation to praise having either a positive or negative effect; there may be huge subjectivities between parents in what they consider as encouraging statements. This is particularly relevant in the sense that researchers have argued that praise is only effective if individuals use statements that focus on specific strengths that the child can learn from oppose to the most used general meaningless phrases, such as 'Good job!' (Taylor, 2009). It is suggested that this general sort of praise can damage the child's resilience whilst also failing to have the positive effect one would expect due it containing nothing that child can develop on. From this point of view, when studies look at children that have been praised for effort vs. intelligence (Dweck, 1998), there is no indicative way of knowing whether the subjects used in each praise group were getting praised in the suggested constructive manner or through the general approach. In reality, it is most likely that it is a mixture of both with differing parenting techniques, hence rendering it hard to confidently make conclusive statements.

Another area that lacks critique is the recent claims that you should not praise your child in areas that they have 'no control over' (Taylor, 2009). When searching through articles to find what these sorts of things include, the most frequent findings were intelligence, physical attractiveness, athletic ability, and artistic gifts. The suggestion that individuals have no control in these areas is an extremely strong claim to make, especially one that no doubt those in favour of the nurture debate would oppose. We may not be able to control the baseline in some of these areas, i.e. if we are not genetically cut out to be the next Da Vinci then it is unlikely that we will ever be the next Da Vinci; we may, under the right circumstances and support however, go on to achieve as throughout school and consider ourselves competent in art. The same is said about physical appearance; even if we are not born a natural beauty, that is not to say we cannot make ourselves attractive with the numerous resources and cosmetics available today. If anything, it would seem not praising a child that is not confident about his/her appearance will only leave the child with low self esteem in a sensitive area, that it will potentially carry with it throughout it's life.

It is fair to suggest that parents that praise their child unnecessarily and falsely can result in negative effects for the child in the long run. It is, however, harsh to suggest that praise is only effective in terms of tangible items and effort. In any bad situation a positive can be drawn, and perhaps this is the message that should be sent to parents- encouraging them to praise constructively at the right time in any situation.

Next we will examine whether praise may be given more constructively in some cultures than others...

6. Cultural Connections: Does Resilience have a Cultural Connection?

The International Resilience Research Project recently examined the universality of resilience through different cultures and ethnicities in the promotion of resilience among children. Data from over 1,200 families with children highlighted universality, however, there were some clear differences in child rearing practices and ways to encourage resilience in children, all of which achieved the same level of success (Grotberg, 1998). This study emphasises the cultural phenomenon of resilience, similar to Ungar (2008), stating that the understanding of resilience requires a cultural and contextual consideration, all of which can exert differing amounts of influence on a child’s life, therefore carrying implications for at-risk populations.

6.1‘Culture of Praise’

Is this just the case of a select few, extreme, American businesses taking the issue of staff appraisals too far? Or does it mark a significant cultural phenomenon, and, if so, what might the consequences of this false praise be?

6.2 Effects on Children’s Resilience from False Praise?

This ‘culture of praise’ in the adult world and workplace may be a continuation of the praise lavished on children by parents and teachers alike. To buck this trend could be to cause a compliment deficit. The Wall Street Journal highlights some social ramifications far graver than any compliment deficit: adults overpraised as children are significantly more likely to be narcissistic at work and in personal relationships (Twenge, 2006).

This damaging finding statement is backed up with research findings from a meta-analysis finding students from a wide sample of American colleges score around 30% higher on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory between 1979 and 2006. Results complement previous studies finding increases in other individualistic traits such as assertiveness, self-esteem, and extroversion. Samples are all from American colleges, therefore conclusions are limited to American society and generations; however findings do support those of previous studies. One of the supported studies includes the results from Foster et al., (2003) that Americans score higher on narcissism inventories than people from other world regions. Future investigations should determine if narcissism, along with trends of over/false/excessive praise, is a trend in cultures other than the United States.

One study by Harber (1998) indicates that some students can become so wary of false praise it can damage their self-resilience and cause a drop in their self-esteem. Thus, the kind of encouragement given by teachers to students and how the students cope with feedback has huge implications. Authors state the important nature of findings as it serves to highlight how a seemingly positive action can have unintended harmful results. Consequently, the promotion of youth development, at least academically, must remain cautious in its offering of any superficial reinforcements without a substantive basis.

6.3 Links between Personality, Traits and Culture

As mentioned, these results complement earlier investigations that have focussed on traits that are closely linked with resilience such as self-esteem; a trait that is highly regarded as an important index of psychological health and well-being (Harter, 1993). Brown and Mankowski (1993) found self-esteem to be associated with lower levels of depression and higher levels of adaptive coping (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). In the quest for higher self-esteem people have tended to praise even where it may not be entirely necessary or true. The results of this in classroom environments have been studied by Mueller and Dweck (1998) finding that, contrary to conventional wisdom and popular belief, praising children for an ability or trait such as intelligence is detrimental to students motivation to achieve.

In conclusion, ‘praise where praise is due’ may hold true, especially so for children, within academic settings and for their development of important qualities including resilience.

7. Further information - articles and videos

Here is a list of interesting sites that you might want to brows through, including magazine and newspaper articles and some videos.

Articles

Baumeister's paper is a summary of key papers in the field of self-esteem that give results contrary to previous thinking, showing that higher self-esteem did not appear to be giving benefits.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44.

This is an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education about Carol Dweck and why the right type of praise is important.

The topic of praise is popular in the news, here is a recent article in the Washington Post.

Carol Dweck’s programme on ‘brainology’ explores how students can increase their achievement.

Praise in the wrong context is covered in a wide range of articles; examples can be found from Christian News to The Wall Street Journal.

Giving children indiscriminate praise should not be considered the same as giving unconditional love, here a child psychiatrist discusses the difference.

Here is what Carol Craig says on resilience from the Centre for Confidence and Wellbeing.

Video

Carol Dweck has been one of the main researchers on mindsets, here is aon Carol Dweck's work that shows some of the experimental work with children and giving them puzzles to work out then either telling them they are smart or that they worked hard.8. Academic references

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44.

Bayat, M. (2011). Clarifying Issues Regarding the Use of Praise With Young Children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31, 121-128.

Becker, W. C., Madsen, C. H., Arnold, C. R., & Thomas, D. R. (1967). The contingent use of teacher attention and praise in reducing classroom behavior problems. Journal of Special Education, 1, 287–307.

Branden, N. (1969). The psychology of self-esteem . New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Brown, G. W., Andrews, B., Harris, T., Adler, Z., & Bridge, L. (1986). Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychological Medicine, 16, 813-831.

Bown, J., Mankowski, T., (1993) Self-esteem, mood and self-evaluation: Change in Mood and the way you see yourself, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 64, 421 – 430

Challen, A., Noden, P., West, A. & Machin, S. (2011). UK Resilience Programme Evaluation: Final Report. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/RSG/AllPublications/Page1/DFE-RR097 (accessed 23 January 2012).

Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in Adolescents: Protective Role of Social Support, Coping Strategies, Self-Esteem, and Social Activities on Experience of Stress and Depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 343 -363.

Dweck, C. S. (2008) The Perils and Promises of Praise. Best of Educational Leadership 2007-2008, 65, 34-39.

Forte, M. , Jahoda, A., & Dagnan, D. (2011). An anxious time? Exploring the nature of worries experienced by young people with a mild to moderate intellectual disability as they make the transition to adulthood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50, 398–411.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R., Delongis, S., (1988) Ways of Coping Questionnaire, Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychology Press

Foster, J., Twenge, J., Campbell, W., (2003) Individual Differences in Narcissism: Inflated Self-views across the Lifespan and around the World, Journal of Research in Personality, Vol. 37, 469 – 4 86

Furnham A., Chamorro-Premuzic, T. & Mcdougall, F. (2003). Personality, cognitive ability, and beliefs about intelligence as predictors of academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 14, 49–66.

Grotberg, E., (1998) Resilience and Culture/Ethnicity examples from Sudan, Namibia, and Armenia, presented at the Regional Conference, International Council of Psychologists, "Cross-cultural Perspectives on Human Development", Italy

Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77, 81-112.

Henderlong, J., & Lepper, M. R. (2002).The Effects of Praise on Children’s Intrinsic Motivation: A Review and Synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 774–795.

Kim YH, & Chiu CY (2011). Emotional costs of inaccurate self-assessments: both self-effacement and self-enhancement can lead to dejection. Emotion, 11 , 1096-1104.

Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1121-1134.

Madsen, C. H., Becker, W. C., & Thomas, D. R. (1968). Rules, praise, and ignoring: Elements of elementary classroom control. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1, 139–150.

Mueller, C. M. & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for Intelligence Can Undermine Children's Motivation and Performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33-52.

Niiya, Y., Brook, A. T. & Crocker J. (2010). Contingent Self-worth and Self-handicapping: Do Incremental Theorists Protect Self-esteem? Self and Identity, 9, 276–297.

Reivich, K. J., Seligman M. E. P. & Mcbride, S. (2011) Master Resilience Training in the U.S. Army. American Psychologist, 66(1), 25–34.

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K. & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: positive psychology and classroom interventions, Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293-311.

Taylor, J., (2009). Parenting: Don't Praise Your Children. Psychology Today.

Twenge, J., (2006) Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled--and More Miserable than Ever Before, Free Press, New York

Twenge, J., Konrath, S., Foster, J., Campbell, W., Bushman, B, ., (2008) Egos inflating over time: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, Journal of Personality, Vol. 79 (4), 875 – 902

Ungar,, M., (2008) Resilience across Cultures, British Journal of Social Work, Vol, 38 (2) 218 – 235

Wierzbicka, A. (2004). The English expressions good boy and good girl and culturalmodels of child rearing. Culture and Psychology,10 , 251–278.

Zimmerman, E. H., & Zimmerman, J. (1962). The alteration of behavior in an elementary classroom. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 5, 50–60.

Moodle Docs for this page

Moodle Docs for this page