Despite all prejudices, 1003 Waldorf schools were counted all over the globe in September 2011 (Bund freier Waldorfschulen, 2011). The question arises: What are Waldorf schools about?

The article in the guardian gives a short and precise overview of the discussion:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2007/oct/30/schools.uk1

Apparently there are a lot of controversies about the wealth and qualification of Waldorf schools. Some parents doubt that this alternative form of education prepares their children well for higher eduction whilst others are absolutely convinced of it. Thus, it is interesting and important to examine this issue.

2. Empirical Research on Waldorf Education

3. Critique

4. Steiner Education in Universities? - An idea

5. Additional Information & Background

The basics of the Waldorf education include the belief that children need three capacities to challenge the tomorrow’s world.

Besides cognitive ability and acquiring information they need to develop thinking, feeling and willing (Petrash, 2003).

Kindergarten:

Education begins in the kindergarten where educators are supposed to support early learning. Petrash (2003) describes it the following: “ Our task as educators, if we wish to preserve what we promote premature ageing. The key to this is to create school programmes that value and protect childhood.”

Conspicuous is the way the rooms are made like. Schwartz (2000) quotes a headmaster visiting a Waldorf kindergarten who described the room as “This room is like something out of the nineteenth century!” There are no books, no posters or computers but wooden, natural furniture and coloured walls. Everything is prepared to offer a natural, learning environment but with opportunities to explore and play (Petrash, 2003).

Elementary and Secondary Education:

Waldorf schools have similarities with average schools concerning the content and educating skills however there are notably characteristics to point out:

First of all, the role of the class teacher has to be considered. The class teacher is committed to remaining with the class for seven or eight years. His or her task includes the daily “main lessons” and as well as teaching some other subjects (Carlgren, 2008). Furthermore, the class teacher has lunch with the class and communicates with the other teachers and parents (Schwartz, 2000). As he or she spends most of the time with the pupils it is the teacher's duty to write a school certification for every pupil at the end of the school year. This certification does not include marks but rather a written statement on the pupil's strength and needs for improvement (Carlgren, 2008).

Another point is the timetable, which is supposed to make an organic whole. According to Steiner it is easiest to think and concentrate during the early part of the day. That is why subjects that need understanding and knowledge are taught in the morning. Later in the afternoon artistic and more practical subjects are scheduled. (Carlgren, 2008)

This idea goes along with the “Main lessons”. Following a spiral curriculum, for three to six weeks the same subject is presented in a long morning lesson (Reinsmith, 1990). This way of teaching allows teacher and students to cover the curriculum intensively, economically and deepening. Moreover, the breaks between the block period lessons enable a process of forgetting and remembering what makes students returning to a subject with new interest and insights. (Trostli, 2001)

Steiner believed that creativity and resourcefulness should become the very essence of the teaching method (Reinsmith, 1990). Hence a common sight in Waldorf Schools is that of children who draw, knit, paint or make music. At one point artistic subjects are supposed to offer the same way of learning as artists do namely through imagination and feeling, story and drama or colour and shape. (Reinsmith, 1990) Furthermore, it is an exercise for the will. “There is no better way of training the will than to practise again and again something one finds difficult.” (Carlgren, 2008)

This emphasis on artistic work can also be found in the composition of own textbooks. Instead of having only printed books students learn to make their own textbooks based on lectures and research (Reinsmith, 1990).

Really unique to Waldorf education is “Eurythmy”. According to Steiner the founder of Eurythmy classes it means “essentially visible speech.” (Steiner, 2004)

Basically it can be described music and speech expressed in body movements or the attempt to make music and speech visible through dance. (Holland, 1989) Pupils move in geometric spirals and figure eights, while older students often work out elaborate eurythmic representations of poetry, drama and music. It is based on the idea that when we speak a sound it is accompanied by a kind of invisible gesture within us. The movements of eurythmy are the visible expression of this gesture. (Carlgren, 2008)

As it is very difficult to describe eurythmy, here are some examples to watch at:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YlxJFDuIZJQ&feature=related

Schieffer and Busse (2001) compared achievement tests of fourth grade economically disadvantaged minority students from a public Steiner school and neighbouring public school in the United States. The tests included subjects like math, reading, social studies, science and language. Result: Over the two years for which data were analysed, the socially disadvantaged students in the Waldorf School did better than the comparable students from the neighbouring school.

Another study carried out in the United States (Smith, 1998) examined that perception of individuals involved with Steiner education by using questionnaires. Result: Large majorities agree that Steiner education successfully enable students to develop a strong sense of self, good life skills and strong intellectual and academic skills.

There is evidence that shows a positive relationship between Steiner education and learning, achievement and pupils’ educational and social development. However, more research is needed since studies are often carried out in different cultural context, what may affect results and are based on a relatively small sample size.After all, however, Steiner’s concept on anthroposophy has to be considered critically and there are some points of criticism that are worth mentioning.

Firstly, the concept is deducted from neo-mythology and has rather a metaphoric character. It has neither any ethical-philosophical foundation nor a socio-cultural dimension and no empirical psychological origin. (Barnes, 1991)

Regarding education, the practice of having the same teacher for eight grades could have down sides if the teacher is not the right one for a child or does not get along with the class. (Upitis, 2003)

Furthermore, in Waldorf schools religion is not taught as a subject at all what has been criticized repeatedly. The non-sectarian attitude is considered critically together with the requirement that teachers study the anthroposophical roots. On these roots Steiner based his methods (Upitis,2003) and that is why the academic basis is questionable.

However, there are still questions whether the timetable is suitable and exhaustive to teach pupils and if they get enough academic knowledge to be prepared for higher education. There are studies pointing out that pupils get on well after school though.

All in all, there is more objective research needed as it seems that there is a lack of neutral literature and constructive criticism about Waldorf education.

According to Steiner, adolescents become adults with the age of 21. From then on they are ready for the highest level of education: self-education. Thus, universities follow Steiner’s idea by letting students work on their own. Nevertheless, there are instructions, regulations and duties to fulfil given by teachers.

One might consider introducing main lessons like those in Waldorf schools. This could lead to a deeper understanding of the topic and give students the chance to deal with the subject matter for a longer time. In addition, the idea of producing own textbooks is comparable to the work of essay writing or research projects in universities. Both requires independent working.

Furthermore, the idea of having only one teacher per class could be implemented in universities to a certain extent as well. For example by having the same lecturer for every course about clinical psychology. However, as there are always lecturers who are specialised in some areas of the subject it is doubtful if this concept makes sense. Besides, university should also prepare students for the professional life.

Nevertheless, the need to prepare seminars and tutorials by reading articles and looking for information is self-education in a way Steiner expected adults to be able to. Hence the university is probably an adequate way to educate adults from Steiner’s point of view.

http://www.steinerwaldorf.org/index.html

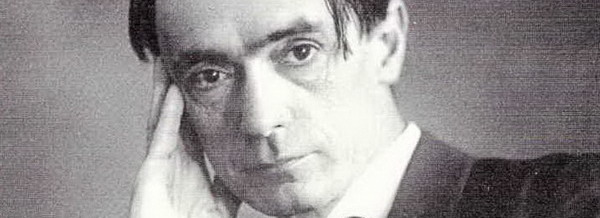

Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Steiner the founder of the Waldorf schools was born 1861 in Kraljeviec (Croatia). After he failed to complete his studies in mathematic, natural history and chemistry in Vienna he decided to pursuit his interests in literary and philosophy (Ullrich, 1994). He was very interested in the work of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. He embarked upon a critical edition of the natural scientific writings of Goethe and also worked as an unpaid assistant in the Goethe and Schiller Archives in Weimar. Influenced by these ideas he wrote the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ and ‘Wahrheit und Wissenschaft’. These writings enabled Steiner to graduate as a doctor of philosophy in 1891 as an external student of Rostock University in Germany (Ullrich, 1994).

When Steiner moved to Berlin became influenced by the avant-garde literary Bohemia, workers movement and the reforming religious thinkers and finally found the Anthroposophical Society.

Steiner’s ideas and success have certainly to be understood against the backdrop of the time. The beginning of the 20th century was a time of social changes (e.g. Russian Revolution, Women rights movement), scientific and technological inventions (e.g. Einstein’s theory of special relativity) and revolutionary ideas towards openness (e.g. Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams).

This change fuelled by the revolutionary mood in Germany 1919 brought Steiner the opportunity to turn his ideas on education in a new school. Thus, he opened the first Free Waldorf School on the 7th of September 1919. At this point, It was mainly drawn from the families of workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart (Germany). (Ullrich, 1994)

AnthroposophyTo understand Steiner’s ideas and work it is necessary to get a brief overview over anthroposophy.

The word ‘anthroposophy’ is derived from ‘antropos’, which means man and ‘sophia’, which means wisdom. Steiner understands it as a kind of rationalized mysticism (Uhrmacher, 1995). His idea of anthroposophy can be summarized in three key points: First of all according to Steiner a spiritual world exists and is intertwined and interpenetrates the sense world. Thus the spiritual reality has a high impact on the material world and problems cannot be solved solely on the material level (Uhrmacher, 1995). This conclusion leads furthermore to the assumption that body and mind are inseparable.

The second premise is that through meditative training of ones organs of cognition, each individual can get the potential to perceive and enter into the spiritual world. Steiner claims that within us are those latent organs of perception that can penetrate the spiritual world. But people have to develop themselves first in order to develop such organs. This development includes not only meditation exercises but also cultivation one’s sense of the beautiful, sympathizing with fellow beings, and thinking and developing a power of observation (Uhrmacher, 1995).

Finally, one develops the faculties of imagination, inspiration and intuition and consciously enters into an objective spirit, which means thinking independent of sensory experience and a stage of precise and clear vision (Ulrich, 1994)

The three stages of Childhood

Steiner’s ideas of anthroposophy are mirrored in his concept of education.

According to him, man is a threefold being of spirit, soul and body (Barnes, 1991). His capacities of thoughtfulness, emotional involvement and intentional activity develop during three seven-years stages from childhood to adulthood. Correspondingly Waldorf schools are divided in the kindergarten, lower school and upper school (Petrash, 2003).

In early childhood that means from birth until around seven years, the young child is primarily active. This is evident for example in the kicking legs of a crying infant (Petrash, 2003). It absorbs the world through their senses and responds in the most active mode of knowing, which is imitation. To satisfy this need for imitation and activity it is necessary to offer opportunities for a meaningful imitation and creative play (Barnes, 1991). According to anthroposophists through activity the young child is most easily engaged and taught (Petrash, 2003).

By entering first grade the child is still eager to explore his environment and the urge to be active does not disappear as well but in the course of time feelings become paramount (Petrash, 2003).

During elementary school the educator’s task is to transform all that the child needs to know into a language of imagination. Therefore the teacher uses for example folk tales or legends. The idea behind it is that whatever “speaks to the imagination and is truly felt stirs and activates the feelings and is remembered and learned” (Barnes, 1991).

What is characteristic for the last stage is the development of the capacity for critical thinking. It shows itself with the onset of adolescence and particularly at the beginning of upper school (Petrash, 2003). Having gone through all stages the adult is finally ready to take up the real task of education namely self-education. (Barnes, 1991)

Bund der Freier Waldorfschulen e.V. (2011). World List of Rudolf Steiner (Waldorf) Schools and Teacher Training Centers. Retrieved March 14th. Available at: http://www.waldorfschule.info/upload/pdf/schulliste.pdf(

Carlgren, F. (2008). Education Towards Freedom: Rudolf Steiner Education: A survey of the work of Waldorf Schools throughout the world. Floris Books: Edinburgh.

Dahlin, B. (2007). The Waldorf School- Cultivating Humanity? A report for an evaluating of Waldorf schools in Sweden. Karlstad University Studies, 2007: 29.

Petrash, J. (2003). Understanding Waldorf Education: Teaching from the Inside Out. Florish Books: Edinburgh.

Reinsmith, W. A. (1990). The Whole in Every Part: Steiner and Waldorf Schooling. The Educational Forum, 54(1), 79-91.

Schieffer, J. and Busse, R. T. (2001) Low SES Minority Fourth-graders’ achievement, Research Bulletin: Research Institute for Waldorf Education, 6 (1), Retrieved March 12th. Available at: http://www.waldorflibrary.org/ResearchBulletin.htm

Schwartz, E. (2000). Waldorf Education: Schools for the Twenty-First Century. Xlibris Corporation: United Kingdom.

Smith, P. (1998) Update: Essentials of Waldorf Education Study, Research Bulletin: Research Institute for Waldorf Education, 3 (1.), Retrieved March 12th. Available at: http://www.waldorflibrary.org/ResearchBulletin.htm

Steiner, R. (2004). The Spiritual Ground of Education.Anthroposophic Press: Great Barrington.

Trostli, R. (2001). Main Lesson Block Teaching in the Waldorf School. Research Bulletin: Research Institute for Waldorf Education. 6 (1). Retrieved March 12th. Available at: http://www.waldorflibrary.org/ResearchBulletin.htm

Ulrich, H. (1994). Rudolf Steiner. Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 24(3/4). 555-572.

Uhrmacher, B. (1995). Uncommon Schooling: A Historical Look at Rudolf Steiner, Anthrophosphy, and Waldorf Education. Curriculum Inquriy, 25(4). 381-406.

Upitis Rena (2003). The Praise of Romance. Journal of Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 1 (1). 53-65